In conversation with Ron Burnett. Published in Cine-Tracts, Vol. 1, No. 4. (Spring-Summer, 1978)

So much of what you are trying to do in your films is a response to the history of the documentary . . . the way in which the documentary has tried to set up a false window/mirror on the world and presumes itself to be showing what is happening in the reality around us but never really trying to bring out the complexity of what it is showing, never bringing out the political, economic and social context and conjuncture of which it is a part. The window presumes a clarity on the part of the filmmaker, a unified view of the world, a homogeneity, a lack of contradiction — all these are perspectives which I think you are trying to work against. There are two levels at which we perceive you operating. One is at the level of the reality that you are trying to depict and show and the other is a level of discourse in which you try to comment upon and politicize the way reality is understood and seen. We would like to understand how you are affected by what you are filming and how you feel you are affecting, politically, that which you are showing. You are trying to include two sets of complex elements simultaneously in the act of filming, does the history of representation, the history of the documentary, the way television works for example — television news — overwhelm the spectator’s capacity to recognize the level of critique which you are trying to construct?

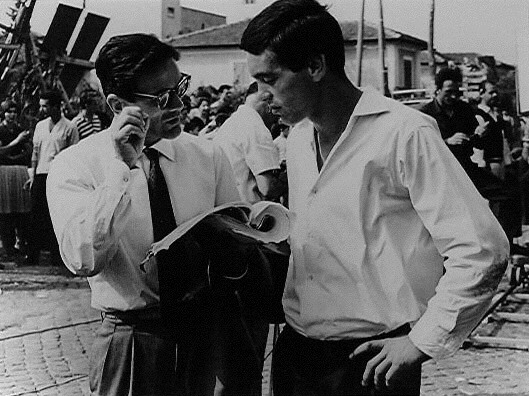

In Springtime, the economist Claude Ménard plays a crucial part. The documentary for me is only part of what I am trying to do. I am trying to account for a thinking process. The portrait of Claude Ménard is a double process: my inquiry into a certain set of problems and his self-reflexive attempt to formulate an answer to these problems. Film as a finished product only presents, the strongest stages, the most effective moments, of a long process; that is, it puts together strong points, and this does not allow for insight into the whole itinerary. Claude Ménard’s interview-section in the film contains moments of uncertainty, where you may feel that he is not in the right setting perhaps, but I include that uncertainty so that the spectator may see where the whole process comes from — mine and his. Everytime I watch Springtime with an audience I get tense because I don’t know if it works, whether or not people will accept this intrusion on their normal viewing

experience. Audiences expect results, polish, they cannot accept weak phases in a product. This is where the history and ideology of representation is so strong. To me it was important to evolve the process and go through these uncertain phases and try and give them a place in any discussion of the film.

Shouldn’t the audience be allowed to have that desire for a finished product?

That depends on the phase you are in yourself as a filmmaker and for me it changes from film to film. Springtime brought resistance when it was shown on T.V. and in the Cinémathèque in Holland, but my next film was well-received. All my films have breaks within them to try and alert the audience to the fact someone, in this case a filmmaker, is presenting them with a point of view but the images also have to touch the audience.

Do you try and provide the audience with tools to unravel the ideology of the documentary? Or do you think that it is the way that the film structures its meaning, frames its enunciations that determines the unraveling? In The Palestinians there are a lot of events presented in terms similar to what we might see on television. How do you try and make the audience understand that what you are doing is a construct — your construct — and not just an objective representation of reality? Is there a means within the film itself for understanding the woman who stands besides her bombed out house for examp le? (ed. note : there is a crucial scene in the film during which the camera examines a bombed out house in Lebanon; we see some older women crying and moaning, they talk of having once lived in a house that is now rubble; the shot is a relatively conventional one and seems derived from cinéma-vérité.)

From one film to another you may even diametrically change your own point of view. I feel there is a strong theme of unity between my films. In fact I sometimes get the feeling that I am doing the same thing in all my films! Always the same story, but taken in different directions, from different viewpoints, and even different viewpoint inside my self . . . although each new film starts at a point opposite from the last one. My film on the Palestinians was responding to the immediacy of the situation and was therefore less concerned with itself at the level of self-reflexivity. And this is an important moral choice and perhaps also an important political choice. Whereas in Springtime it seemed necessary to be outspoken thematically and restrict feeling, in The Palestinians there was certain need to make the film available to a specific group of people . . . the committee in support of the Palestinian cause in Holland. . .a country by the way that has never understood its guilt as being a major cause in its lack of understanding about the Palestinians. . . a guilt, the result of Holland’s policies during the Second World War …

With The Palestinians the play between the representation and what is being shown, between the filmmaker seeing and reproducing, is now shifting to the level of politcal utility. What is the utility of these images in relation to the overall Palestinian situation? Can you ever escape the problems of representation, that is, fictionalizing every situation you enter into?

I fictionalize in order to arrive at truth. In Springtime you have people speaking. There is the pretension of truth — because that is the commitment of the filmmaker — to go and see these people, listen to them talk etc. . . . I cannot guarantee that what they are saying is true but I can establish relationships between the people speaking. In this way I try to create a comprehensive framework for the different speeches. But where the framework is brought in the use of the means is made clear. I mentioned, in relation to The Palestinians that at the beginning of the film there is a photo of an old Jew in the Ghetto. I had each frame printed five times. It is on the screen for two minutes with a small text and phase-like music. I think that this in itself goes against the ethos of the documentary tradition. Here the image is totally flat, it cannot deliver more information than it did at first glance. So you are presented with an image that empties itself out so to speak, and the text that is spoken by me has the characteristic of being a text spoken by a person. I think that in this way you establish a very different relationship to the documentary. It is quite clear that the photo is not there for two minutes to prove anything. It only gives a material basis, an image and a text to the spectator. It also leaves things open, it leaves things unsaid which the spectator can fill in and which establish a framework in which the more truly recorded elements find their place. Also, what I have tried to do in The Palestinians with the commentary was never to present commentary as such over a determined action but to make a separate place for the commentary, so that it would speak over the more aesthetic, passive elements in the film — not dynamic elements. In this way the commentary itself would never interfere with the action itself. In the whole construction (but I think this is more hidden to the audience) there is one important aspect on the level of the didactics of the film, that is, that all the things which are said to people by people somehow refer to spots in the general commentary. The schoolmaster goes over the history of Palestine, the coming of the Jews and the policy of the British — this all reflects back to a commentary spoken much earlier in the film. So you have different angles, mine which is fictional in a way (and the fiction becomes fiction because this guy is telling the same things out of his practice) — the understanding of what is happening is quite different from my enumeration of these facts, or supposed facts in a commentary, which never coincides with an image. The image is a limited set of stock shots which have been designated by a printing process and which are repeated, and to some extent do away with the historical or supposed historical chronology…. I think these are some tools which may enable an audience to see that here there is no pretense to a claim to history or authenticity.

The very crucial difference between The Palestinians and the films that I did before is that with a subject like The Palestinians your moving space is much smaller. In a more pretentious film there is an element of play — the game between the filmmaker and every spectator which is much more in the forefront than the documentary content itself. In The Palestinians the element of play is at a less powerful level than the element of direct speech by the people concerned — and that is a moral choice. It is important to talk of reality in terms of relationships and not just facts. Normally they would be formal relationships, but here the form has shifted in some senses to the content — so that they become relationships of content. So the film has to deliver a set of relationships to the audience which make sense and I think that at that level the film works. As a film it is not authoritarian. It is not saying to the audience, you have been misinformed, this is the way it is. But it brings out a set of more or less disconnected images in a certain structure/construction of relationships and an audience can make sense, or get a certain tone out of it. That’s more important than what is being told exactly. Because I believe that lists of facts — and this is my experience when I see documentary films — are useless, hard to remember. But an overall image stays. To be able to communicate what is happening you have to downplay the facts somewhat to get people to realize that they are looking at a construct; the construct is there and if the spectator is interested or aware, he will see the constructs.

The problem of how you establish the overall tone . . . The desire on the part of many political filmmakers has been to collapse the multiplicity of meanings that are possible or desirable in imagery into one flat directed statement so that all the complexities which make up the process of coming to an understanding of something — all of the complexities making up the process of looking at a moment in history and trying to understand it — all that is collapsed into what appears to be a pure statement of and about reality. And that bind, the political filmmakers bind of, in the one instance wanting in one or two hours to convince an audience of something which has perhaps taken the filmmaker himself or herself many years to arrive at — that desire to completely obliterate all the mediators is a dangerous desire because it is ultimately a desire to objectify the audience.

In The Palestinians the aesthetic is fully there. It is not being collapsed. It is more hidden, more subdued perhaps, but this has to do with a feeling towards the outside world you are dealing with. It is not the result of a calculation towards the audience but it is more or less an intuitive reaction towards the people and the reality in front of the camera . . . formal play should be there to help the communication but a film like The Palestinians is not the arena for me to discover and play with the aesthetic questions.

The Palestinians, by Johan van der Keuken… par medicitv

The tradition of the documentary can be turned around to work in your favour. One has to get away from over-emphasizing the actual effect of the aesthetic and begin to understand that there is a play between the aesthetic and between the history of the conventions of the documentary and a play between what is being represented and the history of representations. It is still possible as a result of the medium itself to use the power of duplication in a positive and political manner. To move too far to the other side has its dangers to, which is that one can over-emphasize, fetishize the way the aesthetic is operating and the way the medium is determining the enunciation. This can dilute the powerful effects that the tradition of the documentary film has had. And it is within that effect, that tradition, that one begins to change the rules of the game. But it can only be done to a point. It can’t be shifted entirely. It’s a really difficult problem. If you negate it entirely you end up with a film which is essentially incapable of moving beyond a limited group of people. If you shift it too much the other way you end up with a collapsing of all the mediators. In between these two poles is the place to be, but not to try and become fetishistic about the necessity of keeping the representation visible as representation all the time.

Whether or not it is possible, with The Palestinians you are faced with making a moral choice . . . Le film ne peut jamais dépasser le public. . . . The film can never get over reality. We can never make a better model than the realities that we are faced with. If we put form as a strong fence before the screen, in front of the audience, we still put it as a fence that shows the audience and ultimately ourselves as ourselves — our own limits of perception. This is also a moral choice. With The Palestinians we had to open up the possibility of perception to people who, up until that point were closed to any communication with anything that had to do with Palestinians. On the level of the écriture of the film, what is very strong are the images of the airplanes, machine-like and unnaturalistic. This image, cannot, within a certain style of writing of a film, be directly connected with the scenes that follow, where people tell how they have been bombed out etc. The truth of people’s speeches is almost naively accepted. I came here to take in what they had to say. It was a primary relationship. But the whole thing in its working, its mechanism as a dramatic representation is questioned by the shots of the airplane in black and white, while the other scenes are in colour. Many people in any given audience, are not consciously looking at what they see, concepts are linked up in the mind of the audience such that the planes are associated with bombing the people. What we deconstruct the audience reconstructs. On the level of what is there materially, you have two realities which on the one hand flow over, one into another and on the other hand are strongly separated from each other. I think these are the tools we use to make clear what we want to do. We came to take in what they (the Palestinians) had to say and not to question whether or not the bombed-out kitchen was in fact the kitchen of the woman showing it to us . . . and that framework in which we organized all these images remains the framework of a conjecture. . . . At times the film is on a more far away level which permits us to see the images which come most strongly towards us in another perspective. It can never be a game which is played, a game of signs or of interpretation of signs which can be separate from our particular attitude towards the subject matter at a given moment.

The way we experience films, or the forms of films that we have seen, particularly in the documentary tradition, is that the flow of rhythms generally speaking, is very difficult to contradict, mainly because even if one is conscious in the making (of a film) of a series of relationships of écriture, that the viewing somehow seems to collapse difference into unity, collapse obvious contradiction into homogeneity and so forth . . . and the problem then rises to another level which is: is it possible to build into the structure of relationships enough of a space, a gap between those relationships so that homogeneity is impossible to arrive at as a spectator? It is not now a question of aesthetics, it is now a question of the politics of communication. If the rhythm of the relationships ends up nevertheless generating unity, then the capacity to recognize it as text for example is lessened, the capacity to recognize the profundity of the work which has gone into generating difference; each coupe is pushed to the side. It is a question that political filmmakers have been struggling with for a long time. And it seems fundamental to film because in the theater at least you can open up those spaces, you can generate that silence, the silence that you try to generate for example in parts of The Palestinians, with the scene around the campfire . . . the moment of silence, which is one of the gaps that we are looking for. (Ed. note: the scene being described has the camera circling a group of Palestinians as they silently eat and rest around a campfire. . . the camera focuses in on their gestures, looks and reactions to each other . . . not a word is exchanged.) But that gap has to be a constant part of the way in which the film enunciates itself, so that it becomes a primary element of the enunciation, as important as the images of the reality being shown.

In response to what was said about silence: to me the silences are there in all my films. If I were able to take all my films some of these silences would be inescapable. Spectators are not accustomed to seeing films which are either silent or contain moments of silence within them. They are unaccustomed to hearing themselves breathe. What happens in front of a piece of silent film is that the audience becomes present again. You go into an inner space somehow by observing the outward appearance of someone in silence. The spectator who is willing to get into it has to project his own feelings into this silent image. It is a silence which represents a possible level of content — of what was already there. Before, I used to use silence in a kind of academic way, and at a certain moment you could state it as a problem of “lecture” — of the presence of a text. But it can also be the statement that goes beyond the overall communication of the film. For me, and this might be a false hope or a false justification, but I now experience it a small step to maturity that I don’t need to make statements separate or apart from the situations I am in. I don’t have to proclaim any philosophy over the heads of the palestinians for example, and Springtime is the most rigorous cut-back of left-over aesthetic, and may be even too much of a cutback. But I can always broaden up in the next film. There were weak moments in certain discourses, Claude Ménard’s for example where I felt the most tension between the fullness of what he has to say and the weak moments before he can say it . . . this is the same dialectic: fullness and emptiness, sound and silence. There the silence is not really silence but maybe a defect, something missing which might be filled in. With regard to the second part of the comment that you made if you could have the same thoughts expressed by someone who had an outward distance towards the role of the person — an actor for example — I’m not sure but I think that the portraits were more or less successful in that each person revealed himself through the process — again Ménard is a good example: In the beginning he is a person who is out of touch with his surroundings, he is pretty much an actor on the wrong stage, and you feel uneasy. Is this guy going to tell me how society functions? And then I think by the third day, he picks up a certain rhythm when he is bringing together different ideas and speculations he develops a certain type of continuity. I used to think of this part of the film as the situation of an actor really getting into his role and finally finding the right approach to that role. This ties into what I feel about the fiction of the documentary. Once he has found his rhythm, then the play of angles of the camera becomes very natural with respect to what he is doing — and the music kicks him in the ass from time to time. Further on I ask him a question and he gets a bit angry. It’s what we needed. These things are not predictable but they put the whole fiction as it were in its place. There is a shot of a cradle which turns out to be an advertising billboard in the street — one moment you are in one space — a huge image of a cradle — and suddenly the noise of the street breaks in. Once more we perceive the poster but this time we perceive it to be convex — it is not flat — it is convex. This also represents the different possibilities of the different degrees of reality of one single image. In Springtime each portrait was located in a definite space mostly enclosed ones. With Ménard a certain void or barrier was part of the portrait, as it was part of the portrait of the German girl. In Springtime you have compartments, there is a kind of overflow of meaning; the earlier stages of the film may seem the more insecure or weaker parts, but as they become retrospective, they work.

Springtime, Three Portraits par medicitv

There is a lyricism which seems to pervade all of your films, a lyricism born out of passion/conviction. It is more sometimes than what the film is trying to say . . . what is the specific kind of relationship which you want to establish with your audience?

What can I say about the level of meaning? To me it is hard to talk about . . . why would a piece of music move you? A marxist analysis is the most valid tool for understanding . . . to talk about reality . . . why is a painting, a song, a film, to some extent understandable to so many people? Another thing about my work, is that I find reality or the experience of life very bewildering. I think that the activity of making films is also the need to create some kind of order in all of this and to find some entry into reality, ways of understanding. Sometimes this happens more on an intellectual sometimes more on the level of intuition. . . or of construction. For me the element of construction is very strong, whether it be the verbal approach or let’s say, relationships of connotation or expected meaning. All that works together to make a construction. The experience of time has always been important to me.

What I am striving for in Filmmaker’s Holiday for example, as far as I am concerned as a person is to get to something which will explain the relativistic aspects of my life. On that level the problem is to have this possibility of relativity without stopping to speak socially — which is also a conflict. Because if you take a stand politically or socially you cannot afford relativity too often. On the other hand it is true that in the development of the individual he should acquire a certain degree of relativity in order to develop or see. Showing a clock is a matter of relativity. Putting it there and seeing that it is only a clock — and in between having the joy of speculation as to what it might mean. Also it’s fun. We shouldn’t forget that an element of play is important even in the most serious of subjects.

I want to see film aesthetics as a relative thing. If I have an aesthetic it functions in a relative way. It is a set of relationships — but as related to outside reality, its quite relative too. This is the core of the matter. The problem is not to annihilate yourself when you are confronted with ugly reality, but sometimes accept the fact that you do not have the power to solve all the problems — or make all the relationships come off. Paradoxically, my main problem as a filmmaker is to overcome the fact that for an audience acceptance of what the filmmaker is saying is fundamental to their experience of the film.

The Filmmaker's Holiday, by Johan van der… par medicitv

That is the bind that Godard got into, which is in evidence in much of his work of the early seventies — the bind of the recognition of the contradiction and yet the desire to suppress that contradiction for the audience. Part of the whole process has to be not fearing the visibility of that contradiction for the audience. For example, in Numéro Deux there is an intensity in the way in which he begins to try and talk about the media, about film, which in one sense becomes demagogic. He seems unable to avoid it and yet he is trying to move away from it. The demagogic becomes a way of continuously re-affirming one’s own statements, of validating one’s, premises. . . .

I saw Numéro Deux as being of the utmost honesty and modesty trying to show what was going wrong with western capitalism.

It seemed more complex than that, in which the image ceases to be an image and becomes a series of signs. Each inner frame is its own sign, becomes its own symbolic expression, its own system of meaning, inter-related to the others but now separate, possibly read as separate, possibly read as part of. . . and that complexity doesn’t deal with the fact that the audience is placed in a difficult position. You have the overall frame operating as a meaning and in it is an implicit narrative; and then you have the subdivisions of the frame which begin to comment on the narrative and comment on the framing itself of the narrative. Then you have the double exposures and the splitscreen which comment on the relationship of exterior and interior space — the relationship of meaning to expression. You have all these things happening, and guiding all if it is the relationship of the typewriter to the written word-langue-parole. It was hard to see within all that how Godard was attempting to make contradiction evident and obvious. It seemed that he wanted to, in a sense, come to a statement as fully as possible, and even though it is the play of a puzzle, it ultimately becomes too powerful.

I still felt that the fragmentation was stronger than the unity of the whole construction . . . the point that he couldn’t get it together was to me the strongest impression. . . the relationships were there but they were breaking off at the same time.

In regards to Filmmaker’s Holiday, I wonder if it is possible to recover the purity of one’s own experience — my experience of making the film is now in the past but my seeing the film recovers the past — and recreates it, constantly negating to generate a new present — this for me is fundamental to film.

Yes, in fact no political film can expect to interact with an audience without dealing with the circuit of exchange of memory and the present. Subjective history is a part of the film both in the filmmaker and in the spectator.

I was looking at it from another angle which is complimentary. Film is completely different in different contexts. Some French critics found Filmmaker’s Holiday to be the example of what my work was about. Dutch audiences were very touched by it. A kind of relief operated, as if to say, he can also be like this. This seemed to be a response to what a lot of people consider the lack of subjectivity in political film…. You can only be objective if you include the subjective moment. Claude Ménard in front of the window is a moment of subjectivity during which I cut in to say, well I’m here too. . . . . I interfere with his speech. I flatten him out literally! The same goes for the use of music . . . someone watching the film once said, Hey someone is playing a piano in the other room! That is the effect. I did go out of the room and play piano, metaphorically. . . . In Filmmaker’s Holiday I ultimately appear as a middle class person — given to middle class pleasures — going out on holiday in more or less touristic setting. I think it is important to show this because it is an important level of my existence . . . it influences what I say elsewhere. . . to negate it would be to negate that level of my films which is always defined by an absence.

—————————————————————————————————–

VAN DER KEUKEN ON SPRINGTIME

“In surveys of the economic situation one is very seldom confronted with the effect it has on the individual, on his perceptions and emotions. I wanted to give a personal dimension to this rather abstract economic situation, which is often perceived by the public as a kind of natural phenomenon. I wanted to show how isolation and loneliness, inherent to our production system, make themselves more painfully felt in a period of crisis.

In the films which I have made over the past few years, the problems caused by the prevailing economic system, capitalism, are shown in a world-wide perspective. In this film Springtime I wanted to see things on a smaller scale and look more closely at a few characters within the somewhat more homogenous society of Western Europe. Without neglecting the cultural differences in this smaller field, I wanted to show that the contrasts between rich and poor, between powerful and powerless, though they may be much smaller in absolute terms, also lay a great strain on the people. . . .

While in most of my films I have used the image and spatial sound as driving forces, in the present film I have mainly worked on the basis of the spoken word. In my view anything can serve as the basis or material for a filmic composition: in this case words.

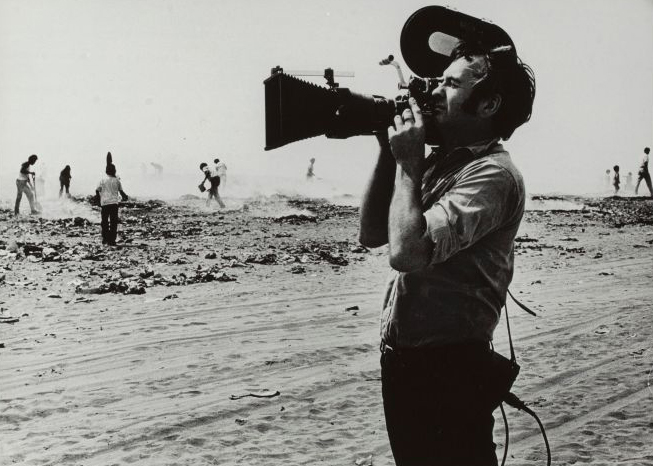

Thus in Springtime we have five characters, each in his own surroundings. Three Dutchmen and two foreigners, three workers and two intellectuals; together they make an overall picture that could be endlessly enlarged. Technically it is not without interest that I was doing the interviews while holding the camera. But while I was working in this very direct manner I wasn’t out to take reality by surprise. I was rather trying to construct a viewpoint through a series of definite visual compositions that were found spontaneously: a kind of instant shooting script, between vérité and fiction.”