The recuperation and citation of images is a film practice as old as cinema itself, and one of the principal strategies within the traditions of avant-garde film and video. In so-called «found-footage films», bits and scraps from the media reality surrounding us are not only taken out of their context and accorded new meanings, but also serve as a basis for critical reflection and analysis. For recycled images call attention to themselves as ‘images’, as products of the cinema and broadcasting industry, as part of the endless stream of information, entertainment and persuasion that constitutes the media-saturated environment of modern life.

The film and video works featured in the programme Ghosting the Image disrupt the usual rhetoric of the media spectacle, characterized by stability and linearity, and turn it against itself. By destabilizing dominant narrative structures and exploring the limits of representation, these works reveal how time, perception and memory are organised. By dismantling the illusion, these films and videos unmask the ambiguity and vulnerability of images, revealing what is being systematically ignored, repressed or left out. As if for a moment the veil of our eyes was lifted, only to find a world of images staring back at us.

Curated by Stoffel Debuysere and Maria Palacios Cruz for the Courtisane Festival, Ghent, Belgium (21-27 April 2008). A selection of these films will also be shown at WORM, Rotterdam, the Netherlands (8-9 May 2008).

1. Thu 24.04 23:00 (Cinema Sphinx) // LATE NIGHT TALES

Peter Tscherkassky

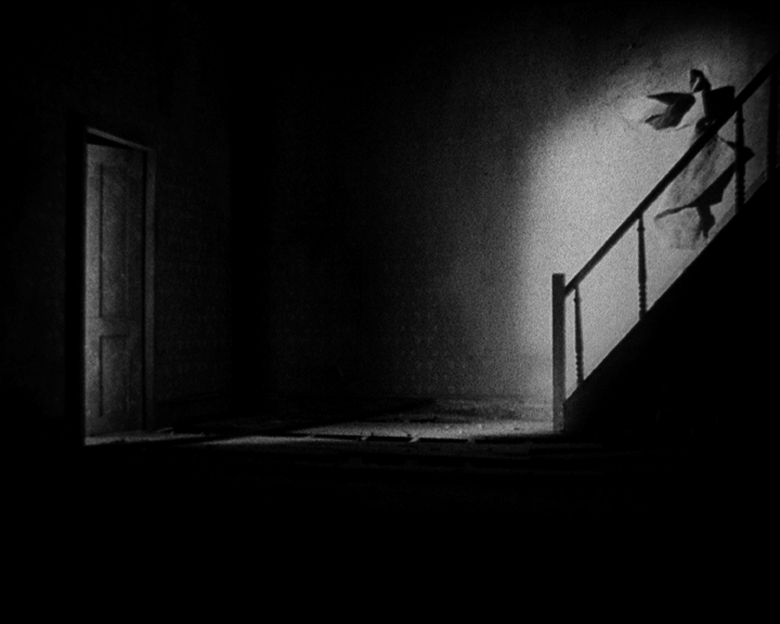

Outer Space

AT, 1999, 10’, 35mm, b/w, sound

Fragments of a Hollywood horror movie were recycled, recaptured and re-exposed frame by frame, resulting in a disquieting confrontation with the codes of narrative-representational cinema and the unearthly qualities of the film apparatus. This is a penetrating cinema that tears itself apart, a journey of self-destruction exploding into unimaginable beauty.

Pere Portabella

Vampir Cuadecuc

ES, 1970, 67’, 35mm, b/w, sound

A hallucinatory reflection on the conventions of horror film. Portabella, a key figure of the Spanish underground film scene, not only documents the shooting of Jesús Franco’s Count Dracula, but also creates, by the means of for instance eliminating colour or using an eerie electronic soundtrack, an alternative version of the original story, revealing at the same time the ways cinematographic illusion is constructed.

2. Fri 25.04 23:00 (Cinema Sphinx) // DISSONANT RESONANCE

Ken Jacobs

Perfect Film

US, 1986, 22’, 16mm, b/w, sound

The rushes of a news report on the assassination of Malcolm X, just as they were found on a bin. Jacobs: “A lot of film is perfect left alone, perfectly revealing in its un- or semi-conscious form. I wish more stuff was available in its raw state, as primary source material for anyone to consider, and to leave for others in just that way, the evidence uncontaminated by compulsive proprietary misapplied artistry, ‘editing,’ the purposeful ‘pointing things out’ that cuts a road straight and narrow through the cine-jungle, we barrel through thinking we’re going somewhere and miss it all.”

Arthur Lipsett

Fluxes

CA, 1968, 23’, 16mm, b/w, sound

Lipsett unfolds his pessimistic vision on the ‘condition humaine’ in an associative jigsaw of found footage. The juxtaposition of divergent episodes of history and popular culture of the 20th century culminates into “a phantasmagoria of nothing”, a somber but urgent reflection on the alienating effects of science and technology, the ruling religions of the Western world.

Abigail Child

Mercy

US, 1989, 10’, 16mm, colour, sound

The last chapter of the series Is This What You Were Born For?, Child’s investigation on the cultural construction of gender identity, sexuality and voyeurism. Through a rhythmic collage of industrial and self-made recordings, pieces of dialogue, music and noise, she dissects the games the mass media play with our private perceptions, drawing the attention to what happens in the margins, the gazes, poses and gestures we ourselves are hardly aware of.

Peter Kubelka

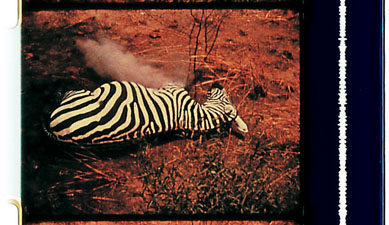

Unsere Afrikareise

AT, 1966, 13’, 16mm, colour, sound

In 1961 Kubelka was hired to document the African Safari of a group of European tourists. Afterwards he hijacked the recorded material and edited it into an analysis of the many layers of violence present in the hunt, the gaze of the hunters and the film itself. The fragmentary and asynchronic montage of images and sounds generates a multitude of connections and associations which, in their turn, evoke a number of metaphorical interpretations.

Stan Brakhage

Murder Psalm

US, 1981, 17’, 16mm, colour, silent

A filmic exorcism of a murder fantasy, drenched in repressed memories and fragments of violent media culture. Brakhage combines educational film footage, television war coverage and Disney cartoons and creates a silent meditation on the world of children today; a world fully surrendered to the mercy of destructive forces. Inspired by some passages of Dostoevsky’s The Diary of a Writer.

3. Sa 26.04 15:00 (Cinema Sphinx) // REMEDIAL RESPONSE

Luther Price

Jellyfish Sandwich

US, 1994, 17’, S8mm, colour, sound

A hypnotic pattern juxtaposing shots of Hawaiian beaches, Chinese ideograms, aerial bombing footage and American football reads as a vague dream sequence, reinforced by a slightly accelerated medley by the Carpenters. With his films Price tries to take a grasp on the breaches, breakdowns and eventual collapse of family, society, body and life itself, in the face of unstoppable philosophical forces.

Naomi Uman

Removed

US, 1999, 6’, 16mm, colour, sound

Using nail polish remover and household bleach, Uman erased the female figures from an old and forgotten porn film. The wriggling holes in the film become erotic zones, blanks on which a fantasy body is projected, creating a new pornography.

Cathy Joritz

Negative Man

DE/US, 1985, 3′, 16mm, b/w, sound

By drawing directly on the celluloid, Joritz comments sarcastically on the speech of an American TV presenter. In a time span of a few minutes he becomes the object of a continuous transformation that is draped on him like a second, celluloid skin. Joritz’s drawings not only serve to adjust the image but also as a way to unmask the representation of authority.

Owen Land

Fleming Faloon

US, 1963, 7’, 16mm, colour, sound

The first 16mm film by Land (formerly known as George Landow) is told to be a source of inspiration for Warhol’s Screen Tests. The image of a staring TV presenter is subjected to a series of manipulations, questioning the optical ambiguity of cinema. Land suggests that if we accept the reality offered to us by the illusion of depth on the flat plane of the screen, we can then willingly ascribe anything as real.

Maurice Lemaître

Un Navet

FR, 1976, 31’, 16mm, colour, sound

A sparkling example of Lemaître’s ‘anti-cinema’, in which he exhorts the audience to revel in cinematographic disgust. He comments tongue-in-cheek on a series of outtakes of commercial films, provocatively summoning the audience to react, and at the same time creates a sensual experience by manually colouring and drawing directly on the film.

4. Sa 26.04 16:30 (Cinema Sphinx) // STORIES UNTOLD

Robert Ryang

Shining

US, 2005, 2’, video, colour, sound

A remixed trailer for Kubrick’s The Shining that adds a totally new meaning to the original, turning the horror classic into a romantic comedy family flick. In doing so, Ryang dismantles the strategies used in conventional Hollywood trailers, revealing them as torturing pretexts and false promises in a tight narrative corset. This video also set a trend for the wave of mash-ups on the Internet.

Matthias Muller

Home Stories

DE, 1990, 6’, 16mm, colour, sound

A collage based on clichés and stereotypes of 1950’s and 1960’s Hollywood melodramas. Muller transforms a range of female gestures and movements into a grammatical construction of paradigmatic elements and condensates them into an elegy of fear. The film does not only comment on the gender politics of classic cinema, but also exposes our own voyeuristic gaze.

Luther Price

The Mongrel Sister

US, 2007, 7’, 16mm, colour, sound

A handful of unrelated scenes from obscure instructional and fiction movies were edited together into an intense and shocking psychodrama. In his works – very often unique prints – Price creates a staggering universe of penetrating images, insistent rituals and disrupted film material, in which he deals merciless with his obsessions; hermetic but visceral evocations of emotional disturbance on the verge of psychosis.

Martin Arnold

Alone. Life Wastes Andy Hardy

AT, 1998, 15’, 16mm, b&w, sound

Third part of a trilogy in which Arnold deconstructs a series of classic Hollywood films, through a process of compulsive repetition. Scenes and gestures are surgically dissected and moulded into neurotic rhythms, turning the hidden messages of sex and violence inside out. The stuttering sounds raise the underlying tensions until they are on the verge of bursting out.

Nina Fonoroff

Some Phases of an Empire

1984, 9’, S8mm, colour, sound

A reconfiguration of images from Quo Vadis, the 1951 epic Hollywood spectacle, rephotographed and edited into a densely layered contemplation of themes such as power, sexuality and aggression. The soundtrack, which includes a spoken version of the children’s book “Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm”, accentuates the subjacent tensions in the original film.

Ken Jacobs

The Doctor’s Dream

US, 1978, 25’, 16mm, b/w, sound

A reinterpretation of a 1950’s television drama. Jacobs reedited the film radically, starting with the shot that was numerically the middle shot, followed by the shots that came inmediately before and after, only to continue skipping back and forth. The deconstruction of the linear structure unravels a strong sexual echo, hidden in the triviality of the original story.

Maurice Lemaitre

The Song of Rio Jim

FR, 1978, 6’, 16 mm, b/w, sound

A homage to Hart and Ince, mythical ancestors of the Western film. The narrative structure on the soundtrack develops as a traditional cowboys-and-indians tale, but the spectator is denied any access to a visual representation of what is being heard. The screen remains black, leaving us to our own memory and imagination. The radical use of monochrome images questions the basic conditions of cinema, exploring the relation between hearing and seeing.

5. Sa 26.04 19:30 (Artcentre Vooruit) // TIME AFTER TIME

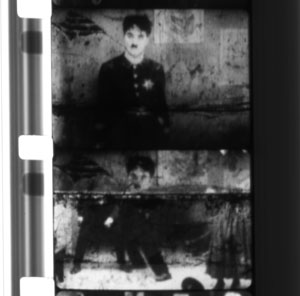

Saul Levine

The Big Stick / An Old Reel

US, 1973, 11’, 16mm, b/w, silent

Levine spent six years reediting 8mm prints of some of Charlie Chaplin’s shorts which he juxtaposed with television images of an anti-war protest. A self-study in montage, narrative ascesis and the amazing power of caustic rhythms, it serves at the same time as a a subtle comment on the duality of society in North-America, torn between passivity and activism, privilege and exclusion.

David Rimmer

Bricolage

CA, 1984, 11’, 16mm, colour & b/w, sound

A reflection on the nature of the cinematographic image and the quality of perception, based on a diverse range of television footage. Rimmer isolates specific passages, intervenes radically on the texture and structure of the film and explores the relation between statis and movement. The repetition, deceleration, and spatio-temporal dislocation of images and sounds provoke the building of a metaphysical tension.

Keith Sanborn

Operation Double Trouble

US, 2003, 10’, video, colour, sound

A “détournement” of a propaganda film produced by the American army. By repeating each shot twice, Sanborn pushes the strategic manipulations of the original, both in terms of montage and ideology, bare to the surface. The echoing effect destabilizes the transparency of the narrative codes and provides an insight into the functioning of audiovisual media and our way of relating to it.

Kirk Tougas

The Politics of Perception

CA, 1973, 33’, 16mm,colour, sound

Segments from the trailer of The Mechanic, an action flick with Charles Bronson, are continuously repeated over a period of a half hour. The sound and image quality constantly deteriorate until both picture and sound assume the status of “noise”. The “mechanic” Bronson, as a protagonist of destruction caught in an endless loop, is a metaphor for mechanized perception, photographical reproduction, cultural production and consumption.

6. Su 26.04 16:30 (Cinema Sphinx) // GLANCING BACK

Vanessa Renwick

Britton, South Dakota

US, 2003, 9’, 16mm to video, b/w, sound

An intriguing film built out of portraits of children on the streets of a deserted city in the 1930’s. Their brutally honest staring gaze betrays an image of a world without images, as well as the perspective of an uncertain future that already belongs to the past. James Benning: “Not only found footage, but a found film made 60-some years ago directly addressing contemporary structural concerns.”

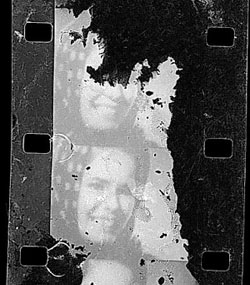

Brian Frye

Oona’s Veil

US, 2000, 8’, 16mm, b/w, sound

A short screen test of Oona Chaplin, her only film-record, is reconstructed into an intense meditation on seeing and being seen. The original shot was rephotographed, mutilated, exposed to chemicals and even buried. The result is an unearthly film portrait, with occasional spots of black emulsion, creating a continuously shifting exchange of glances between the image and the spectator.

Lewis Klahr

Her Fragrant Emulsion

US, 1987, 10’, 16mm, colour, sound

An obsessional homage to Mimsy Farmer, a 1960’s sexploitation movie star. Strips of cut-up 8mm film are glued into a collage, projected and re-photographed. Klahr’s internal montage emphasizes the materiality of film and uncovers the subtle incisions and gestures of the not-too-subtle narrative original.

Morgan Fisher

Standard Gauge

US, 1984, 35’, 16mm, colour, sound

An autobiographical account of Fisher’s experiences as an editor in the commercial film industry during the early seventies. Filming a succession of divergent film scraps rejected at the editing stage, Fisher comments on the origin and meaning of each image, thus exploring the mechanisms and conditions of film production, in both its materialistic and institutional aspects.

Thanks to Dominic Angerame (Canyon), Martin Arnold, Joke Ballintijn (Montevideo), Christophe Bichon (Lightcone), Brigitta Burger-Utzer (Sixpack), Abigail Child, Pip Chodorov (Re:voir), Benjamin Cook (LUX), Xavier García Bardon (Bozar Cinema), Morgan Fisher, Nina Fonoroff, Brian Frye, Helena Gomà (Films 59), Michaella Grill (Sixpack), Will Hanke (no.w.here), Ken and Flo Jacobs, Brett Kashmere, Richard Kerr, Helena Kritis (MuHKA), Saul Levine, Marie Losier, Mark McElhatten, JJ Murphy, Mark Nash, Pieter-Paul Mortier (STUK), Pere Portabella, Luther Price, Vanessa Renwick, William Rose, Robert Ryang, Keith Sanborn, Mike Sperlinger (LUX), Astria Suparak, Peter Taylor (Worm), Anabel Vázquez, Mark Webber, Karl Winter (FDK)…