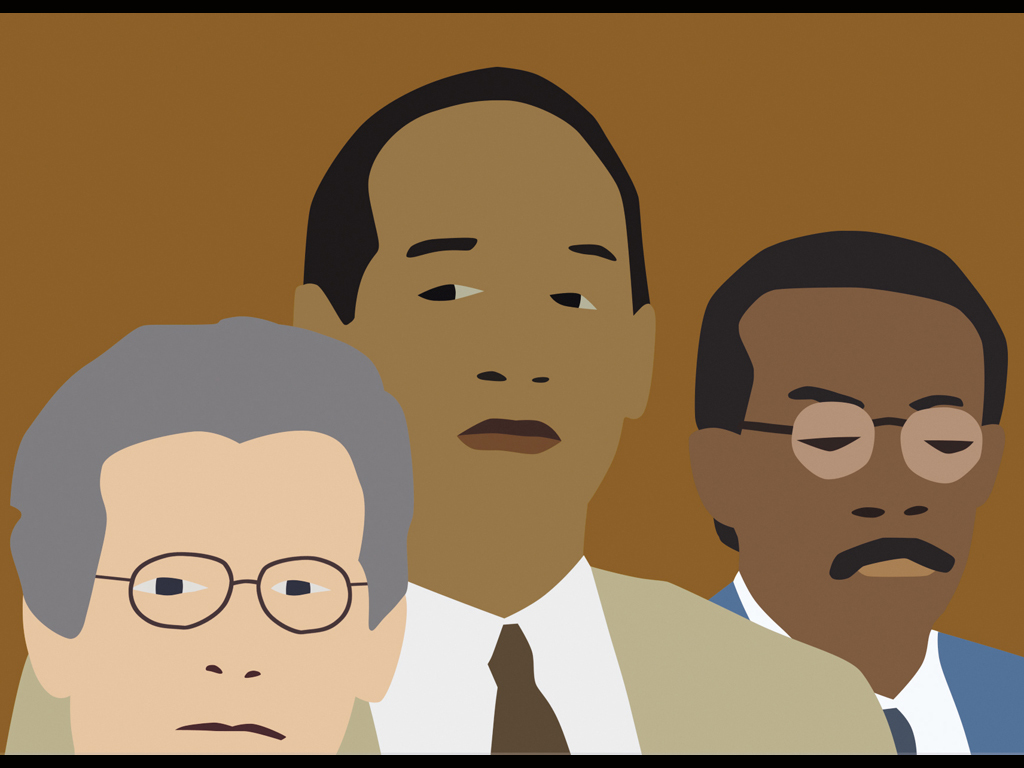

WITHOUT A TRACE

Erasing Inscription, Inscripting Erasure

Thursday 29 January 2009, Art Centre Vooruit, Gent (BE), 20:00.

Program produced by Courtisane, in collaboration with Atelier Graphoui.

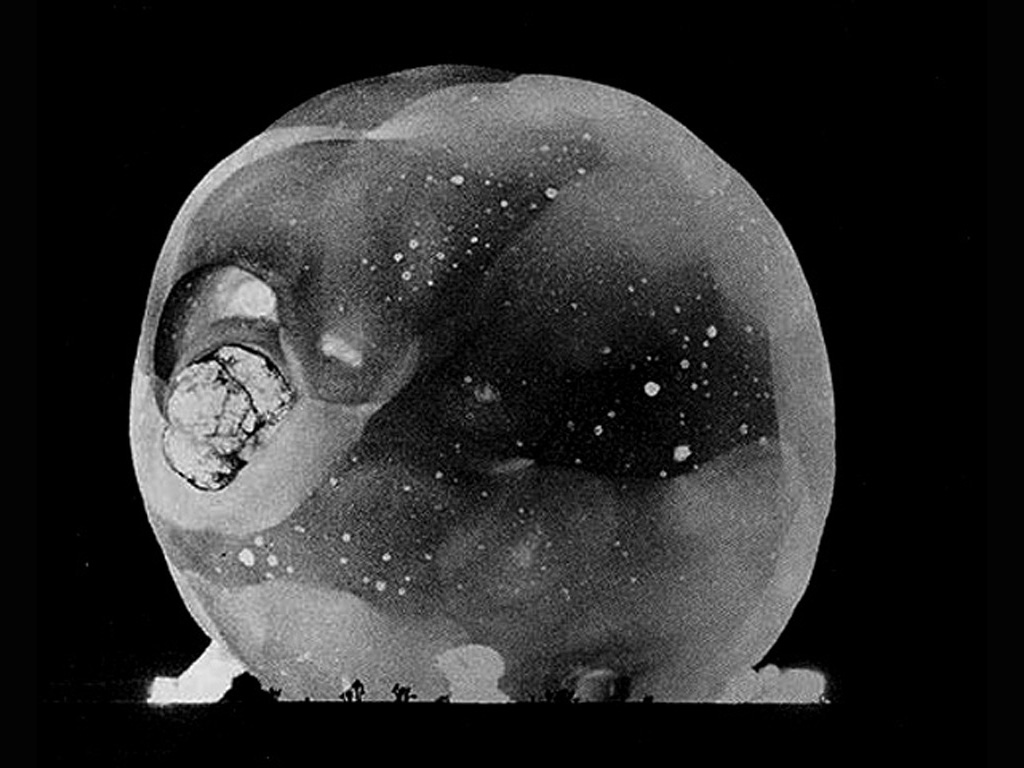

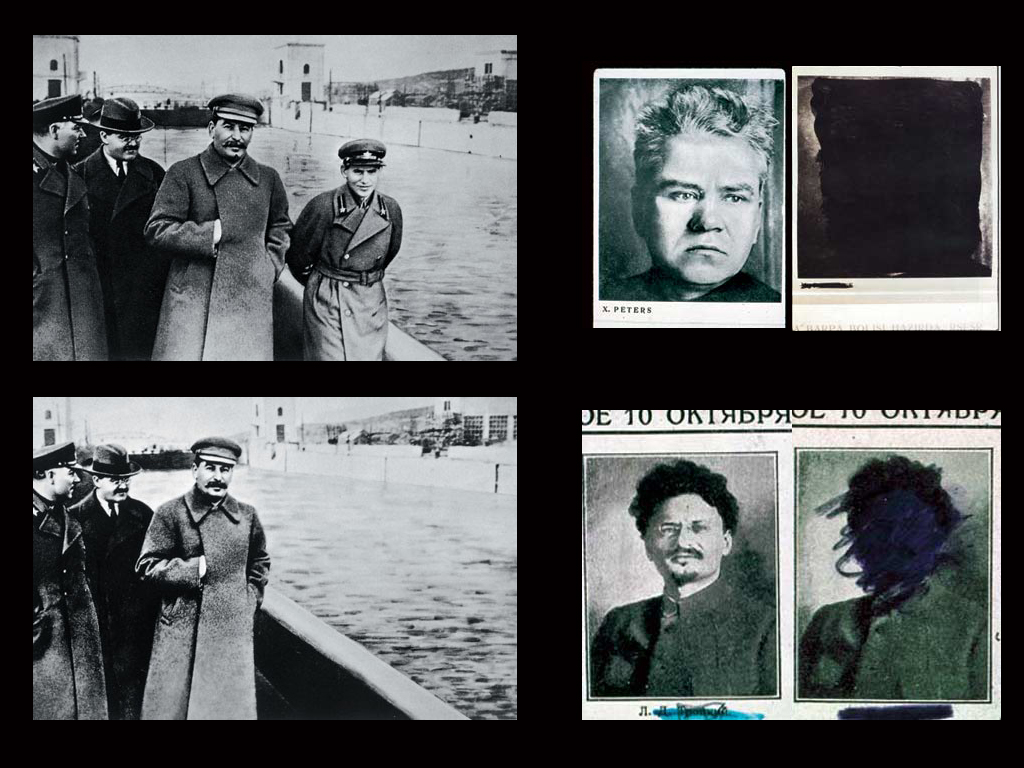

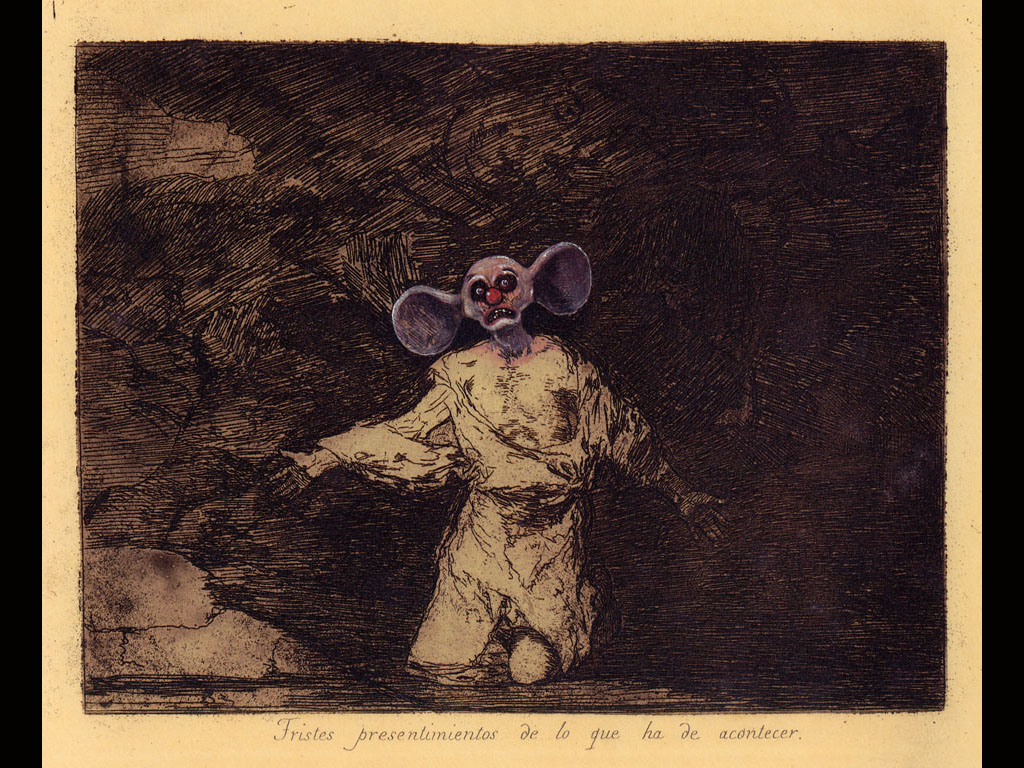

To erase, remove, rub out or conceal signs and images has never been as easy as it is in today’s era of digital hybridization. The immense possibilities in image processing, compositing and trimming have led to the development of a “Photoshop Reality”, a corrected reality which has penetrated unnoticed the heart of our visual culture. However, the act of erasing is never without trace: there always remains a residue, a print upon the surface, a ghost where once was an image. Whether we are speaking of bare scratching or of calculated digital layering, each erasure leaves a trace behind, each absence suggests a (missed) presence. This ambiguity is even stronger in the context of the moving image, which only exists itself thanks to a sort of progressive “erasure”, each image canceling the previous one. Elimination and inscription come together. The act of erasing, “of” and “in” the image, unavoidably leaves the trace of an event underway. It makes the new visible to itself as it redefines what is visible in the old. The film, video and media works in this programme use the idea and the gesture of removing as the basis for an exploration of the tension between presence and absence, appearing and disappearing.

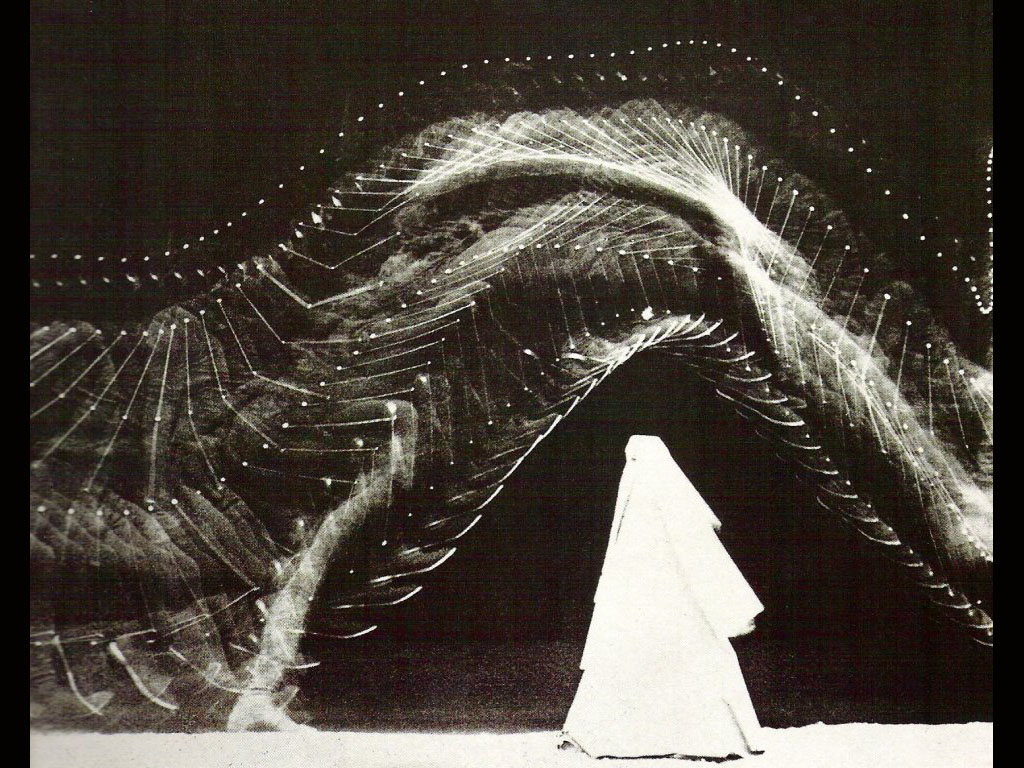

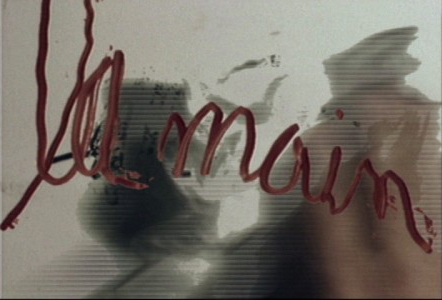

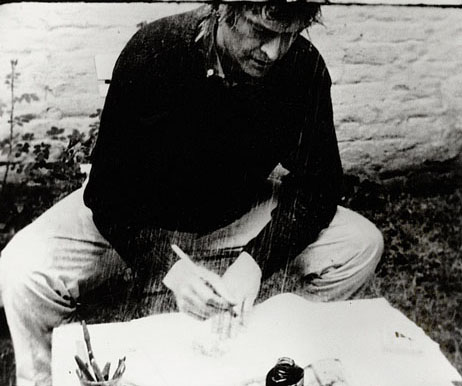

Pierre Hébert

Enkel de Hand (Only the Hand)

CA, performance, 30′

In 2007 the attention of the Canadian animation artist Pierre Hébert was brought to the sentence “Only the hand that erases can write the truth”, generally attributed to the German mystic Master Eckhart. Hébert was not only interested by its inherent paradox, but also by the fact that that it centered on the gesture of erasing – a central element of his live animation performances. In fact, the “animated” movement can only exist thanks to the act of erasure. The sentence would be come the base for a new performance, which will be carried out in Dutch for the first time in Ghent. “The objective of associating the austere theme of erasing carried by the sentence to the burgeoning abundance of virtually all the languages add another layer of paradox and gives a less unilateral value to the whole enterprise : to advent truth must not only face the exercise of taking away all superfluities, but also engage itself in the infinite repetition of all the idioms of mankind.”

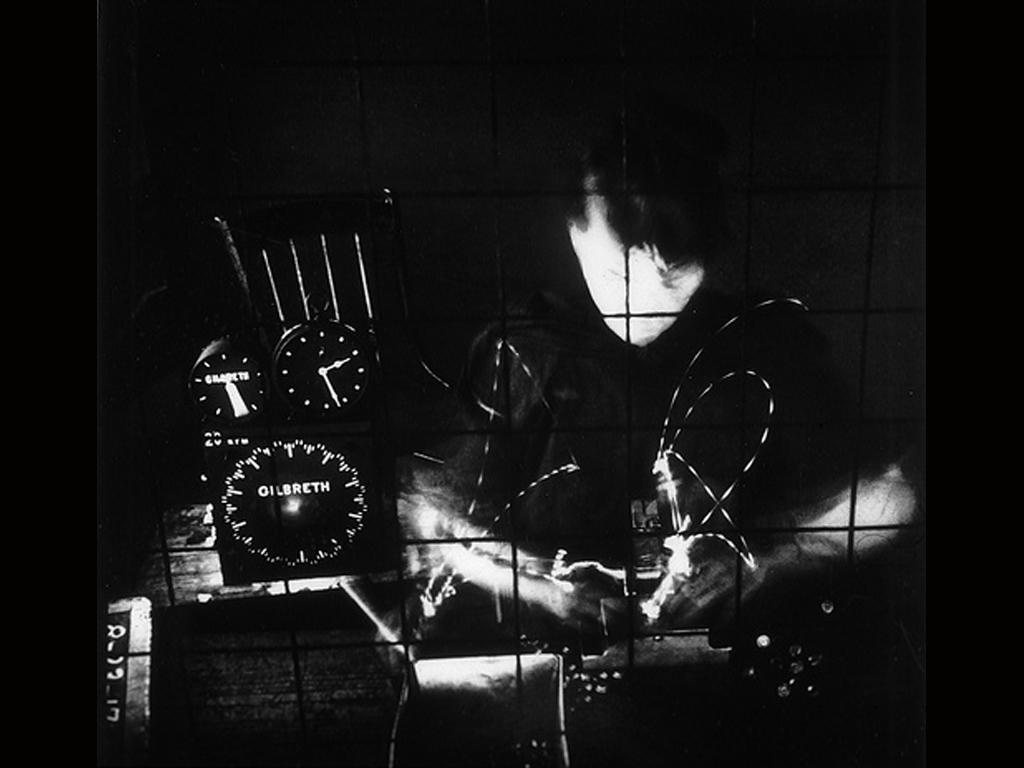

Martin Arnold

Deanimated

AU, 2002, video, b/w, sound, 60’

In this installation, filmmaker Martin Arnold deconstructs an old American horror film. Thanks to digital technology, he removes all the actors one by one, leaving the deserted cinematic space to become the film’s actual leading actor. Arnold turns The Invisible Ghost (from 1941) – a rather atmospheric murder tale in which invisibility and ghosts play no role – into a literally inanimate film. The camera’s eye wanders around aimlessly through sets devoid of human life, unable to find a face in which to read fear or desire, in which to embody the point of view of the murderer or of the vitctim. Disappearance, a classical motif in crime and horror films, is intensified and escalated in Deanimated, up to evacuation. The dramatic soundtrack accompanies the visible traces of events which seem to come out of nowhere before dissapearing into the void again. A voice speaks. A revolver is shot. A cloud of dust rises and dissipates again.

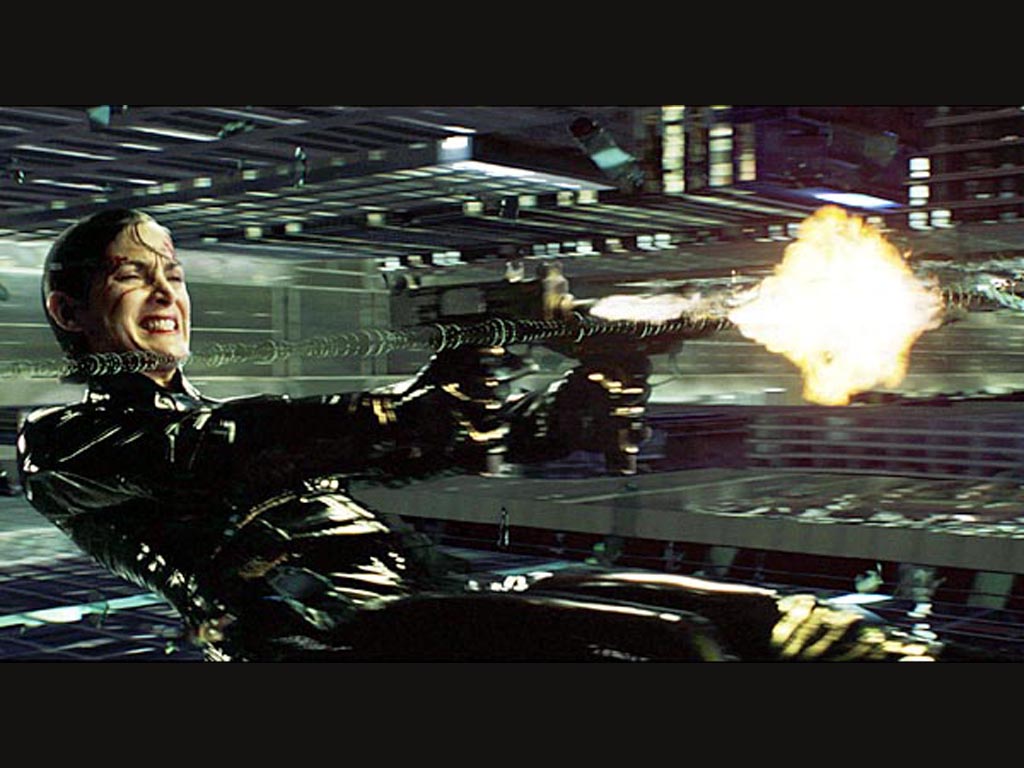

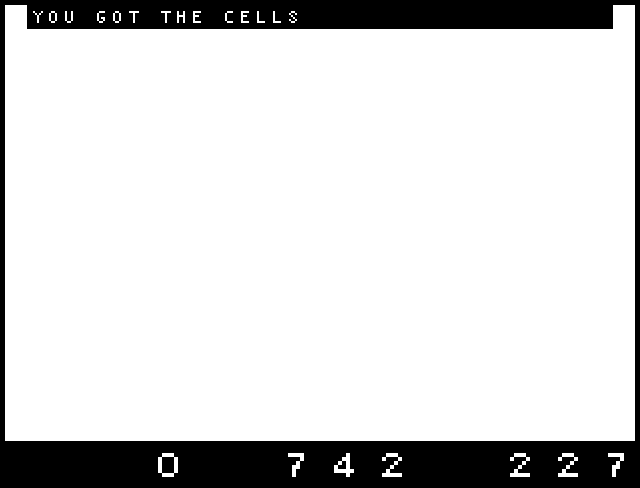

JODI

Untitled Game (‘Arena’ version)

NL/BE, 1996-2001, game mod

“Quake undressed by the gamers themselves”. Untitled Game is a set of modifications, or ‘mods,’ of the video game Quake 1. There are 13 versions of the piece for PC and 12 for Mac. Untitled Game was made just as game modifications began to gain widespread recognition as an art form unto itself. JODI (Joan Heemskerk and Dirk Paesmans) made the piece by altering the graphics of Quake as well as the software code that makes it work. Their mods reduced the complex graphics of Quake 1 (intro Level 1) to the bare minimum, aiming for maximum contrast between the complex soundscapes and the minimal visual environment. For the mod ‘Arena,’ JODI took this principle to the extreme: they completely erased (actually rendering) every graphical element of the game, turning monsters, characters and backgrounds all to white.

Naomi Uman

Removed

US, 1999, 16mm, colour, sound, 6’

Using nail polish remover and household bleach, Uman erased the female figures from an old and forgotten porn film. The wriggling holes in the film become erotic zones, blanks on which a fantasy body is projected, creating a new pornography.

Tammuz Binshtock

Kadooregel

IL/NL, 2001, video, color, sound, 1’

“No Ball, No Glory. Highlights of the ‘Match of the Day’. It’s a strange football game, with both teams missing plenty of good opportunities. Expect to see excellent teamwork, real effort & motivation combined with high-quality soccer moves. One of the best no-ball games ever! “

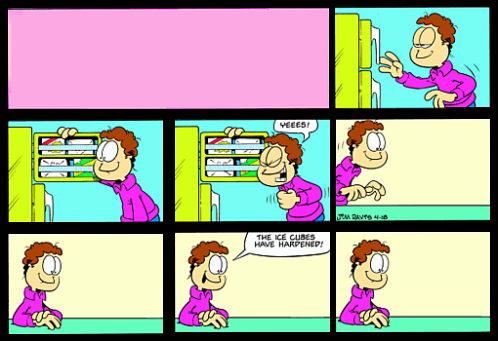

Stephen Gray

Beep prepared

UK, 2002, video, color, sound, 5’

“What is Road Runner without Willie E. Coyote, what is a cartoon without protagonists? What remains of the longest running and most existential series of sketches, once the actors have left the stage? Part one of a deconstructivist trilogy.”

Natalie Frigo

November 22, 1963

US, 2004, video, color, sound, 1’

“November 22, 1963 presents the Zapruder footage of the Kennedy assassination with JFK removed from each frame. Experience of this event was/is almost exclusively through television; interestingly, the original footage was corrupted before it was released to the public. Manipulation of the footage changes not only our experience, but the assassination-in-itself is forever altered. If this version were shown in place of the “original” footage, our memory of this date would be tied to Jacqueline’s ride in Dallas, not JFK’s assassination.” (Natalie Frigo)

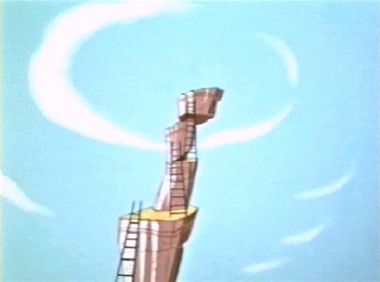

Spike Jonze & Ty Evans

Invisible Boards

US, 2003, video, color, sound, 2’

A short fragment from the film “Yeah Right !”, a cinematographic ode to skateboarding. Filmmaker Spike Jonze, internationally acclaimed for his music videos and the long feature film “Being John Malkovich” and a long time skateboard fanatic, enhances the elegance and agility of the skaters with the help of digital technology. In this clip, a bunch of skaters seem to be jumping and sliding on thin air, an effect obtained using “Green Screen” technology.

Marcel Broodthaers

La pluie (Projet pour un texte)

BE, 1969, 16 mm, b/w, sound, 3’

Broodthaers is filmed in his back garden, while absorded in the process of writing. Equipped with paper, ink and a feather pen he begins to scribble when it starts to rain. The text is constantly erased, but the artist doesn’t seem to mind. A melancholic and allegoric reflection on artistic production, authorship and cinema, that particular medium which constantly doubts between stasis and movement, between writing and erasing.

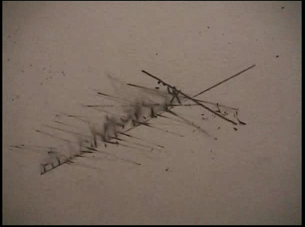

Denis Savary

Le Bourdon

CH, 2004-2007, color, 15’30, sound

In Denis Savary’s animated drawings the act of erasure holds a central place. He draws, erases and draws again successive images on a single sheet of paper, photographing each phase of the process. His little figures come to life in a fog of stains and traces, as if each movement brought carried along the ghosts from the past.

Matt McCormick

The Subconscious Art of Graffiti Removal

US, 2001, 16mm, color, sound, 16’

“It is no coincidence that funding for “anti-graffiti” campaigns often outweighs funding for the arts. Graffiti removal has subverted the common obstacles blocking creative expression and become one of the more intriguing and important art movements of our time. Emerging from the human psyche and showing characteristics of abstract expressionism, minimalism and Russian constructivism, graffiti removal has secured its place in the history of modern art while being created by artists who are unconscious of their artistic achievements.”

Martijn Hendriks

the Birds without the birds (excerpt)

NL, 2007-ongoing, video, color, sound, 3’

Martijn Hendriks is fascinated by the potential of negation and the condititions under which a non-productive gestures becomes productive. By drawing the attention to what remains after the objects of our attention have been erased, sabotaged of shown to contradict themselves, he questions our relation to images and the expectations of visibility and availability. In recent video work such as This is where we’ll do it, a series of manipulated You Tube clips, or The Birds without the birds, in which he uses fragments from Hitchcock’s The Birds, the absence of essential elements from well known images brings unexpected notions to the foreground.

———————————————————————————————————————————————————

Thanks to Martin Arnold, Tammuz Binshtock, Marie-Puck Broodthaers & Maria Gilissen, Natalie Frigo, Stephen Gray, Pierre Hébert, Martijn Hendriks, Jodi, Cindy Banach (Palm Pictures), Natalie Farrey (MJZ), Dominic Angerame (Canyon), Denis Savary, Elodie Buisson & Frances Perkins (Galerie Xippas), Christophe Bichon & Emmanuel Lefrant (Lightcone), Marie Logie (Auguste Orts), Pieter-Paul Mortier (STUK), Vooruit, Bozar, Atelier Graphoui