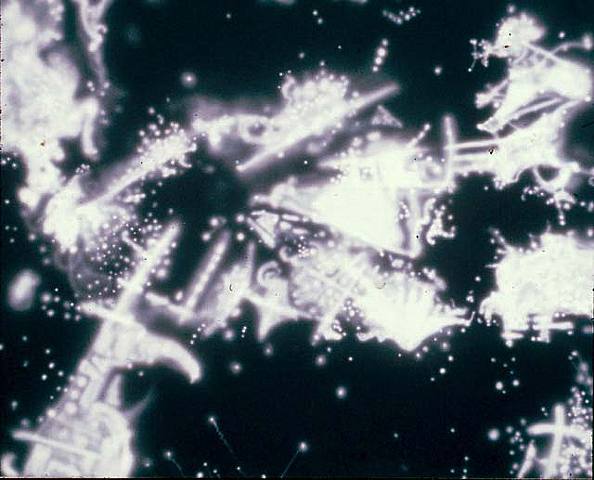

“The daytime to me is about total disappearance, because there is an even light that floods everything out, but at nighttime one can light and spot light. So I see the nighttime as being where I can kind of come into my own, and the daytime is about my absence.”

Jack Goldstein in ‘Wir Männer die Technik so Lieben’ (Stefaan Decostere, 1985)

Jean Fisher about Goldstein:

– To see is that sense of loss, of an appearing disappearance, that is always behind –

“If Goldstein’s spectacle holds us in a thrall that seems both disturbing and imperative, it is because the work’s function is to lay bare the image of the image with all the tyranny that it exerts upon us. Like the prisoners in Plato’s allegory of the cave, we are reluctant to tear our eyes away from our illusions, to break the spell of desire that captures us in its play of nocturnal shadows. Through all the manifestations of the spectacle – the masquerade, the carnivalesque, the cinematic – the immobilized, fascinated subject becomes, in the dark, other than himself. There our fear of the body’s temporality and physicality recedes into forgetfulness, and we can spin our dreams of immortality. To go into the light is to risk the blindness of the absolute insight of the gods.

Such is the paradox of the sublime sensibility alluded to in Goldstein’s painted spectacles: an ecstatic vision of a transcendental self, and an abject self that contemplates the terror of its own effacement by powers beyond its comprehension. In 19thC American art, the sublime was expressed through a landscape of light and space, evoking immensity, silence, and the potentially catastrophic with a tragic theatricality that we find recurring in post-Modernism. For the late 20thC this ambivalence is expressed through the mediated, cinematic spectacle of technology, in the face of which the subject is both remote and anonymous, denied ‘spontaneity’. To image this Heideggerean dread, to use technology’s own devices is, for Goldstein, to exert a measure of ‘control’ over its effect. We may now begin to see the Promethean rather than literal dimension of the artist’s images of impending disasters, warplanes and ‘burning cities’, and their relationship to the cosmic energies described in the more recent paintings of lightning, volcanoes and eclipses.”

Here’s a fragment from ‘Wir Männer die Technik so Lieben’ with parts of interviews with Goldstein and Paul Virilio (see also here). If you’re interested in seeing or showing this (great) video, please contact Stefaan Decostere.

image: Jack Goldstein, Untitled, 1981 (Oil on masonite, 49 x 61 inches)