By Jean-Luc Godard

Originally published as ‘Pour un cinéma politique’ in Gazette du Cinema (September 1950). English version is available in ‘Godard on Godard’, edited by Jean Narboni (The Viking Press, 1972). Translated by Tom Milne.

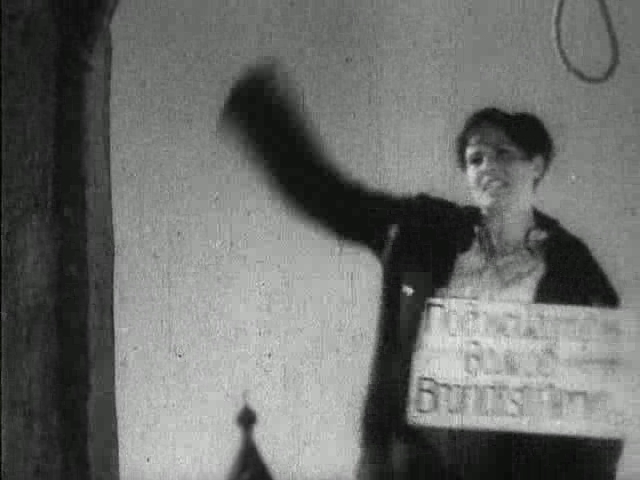

One afternoon towards the end of a Gaumont newsreel, my eyes widened in pleasure: the young German Communists were parading on the occasion of the May Day Rally. Space was suddenly lines of lips and bodies, time the rising of fists in the air. On the faces of these young Saint Sebastians one saw the smile which has haunted the faces of happiness from the archaic Kores down to the Soviet cinema. One felt for Siegfried the same love as that which bound him to Limoges. (1) Purely through the force of propaganda which animated them, these young people were beautiful. ‘The beautiful bodies of twenty-year-olds which should go naked.’ (2)

Yes, the great Soviet actors speak in the name of the Party, but like Hermione (3) of her longings and Lear of his madness. Their gestures are meaningful only in so far as they repeat some primordial action. Like Kierkegaard’s ethician, a political cinema is always rooted in repetition: artistic creation simply repeats cosmogonic creation, being simply the double of history. The actor infallibly becomes what he once was, the priest. The Fall of Berlin and The Battle of Stalingrad are Masses for a consummation.

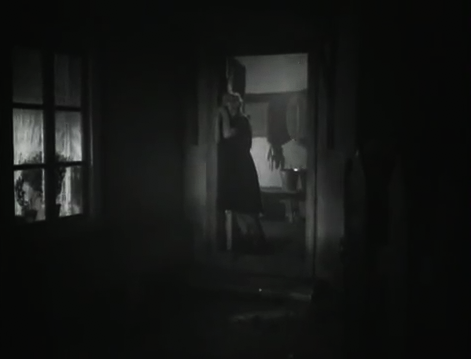

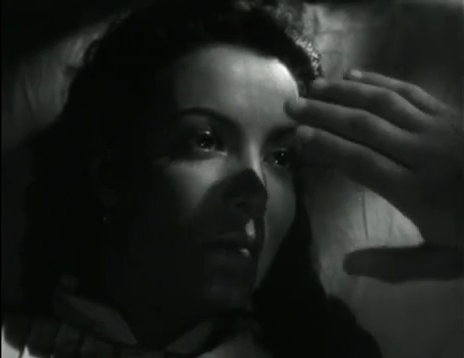

In relation to history, the Soviet actor interprets his role (his social character) in two ways: as saint, or as hero. Corresponding to these two basic agencies are two major currents in the Soviet cinema: the cinema of exhortation and the cinema of revolution, the static and the dynamic. ‘In the former the expression outweighs the content, and in the latter the content outweighs the expression’ (Marx). Whereas in Michurin or The Rainbow the plot takes first place and so articulates the movements of the characters, in Zoya and Ivan the Terrible ‘the consciousness of self which transforms a class into a historical actor forms part of the revolutionary act. It engages itself in the drama of History through the spontaneous and passionate poetry of the event’ (H. Rosenberg). And the reason I admire The Young Guard so deeply is that it oscillates between these two poles, a heart beating ceaselessly between the cult of the Absolute and the cult of Action. One remarkable shot sums up not only the aesthetic of Sergei Gerasimov (who tells his actors he will not be content unless he finds both Rastignac and Julien Sorel (4) in them) but perhaps of the whole Soviet cinema: a young girl in front of her door, in interminable silence, tries to suppress the tears which finally burst violently forth, a sudden apparition of life. Here the idea of a shot (doubtless not unconnected with the Soviet economy plans) (5) takes on its real function of sign, indicating something in whose place it appears. And it is curious that this sign acquires formal beauty only at the moment of its defeat:* the village fleeing before the invader, the arrival of the Germans, shown in a single shot with fantastic virtuosity, the death of the young people, intensified in effect by repeating the same camera movement five times. These moments are brief, but their very swiftness seems everlasting, ‘as the child creates a world out of a single image’. (By what strange chance are these heroes in their darkest hours arrayed in the vestments of our childhood? Zoya barefoot in the snow, Ivan rolling at the feet of the Boyars, Maria Felix with revolver in hand to prevent the great sacrilege, the violation of this woman who is as much part of us as the earth.)

Aside from the Soviet cinema, there are few films revealing such deep political experience. No doubt only Russia feels at this moment that the images moving across its screens are those of its own destiny. (Another significant shot in The Young Guard shows a young girl unable to cry because she is a poor actress, but one look at her actress-comrades weeping for the sacred cause is enough to bring tears flooding to her cheeks.) If one excepts the Giralducian Kuhle Wampe by Brecht and Dudow,

(0 dark young girl

Why do you weep so

A young officer in Hitler’s guard

Has ensnared my heart)

the Nazi propaganda film might be defined in these words by Georges Sorel:(6) ‘an arrangement of images capable of provoking instinctive feelings corresponding to the manifestations of the war engaged . . . against modem society’. It is impossible to forget Hitlerjunge Quex, certain sequences from Leni Riefenstahl’s films, some fantastic newsreels from the Occupation, the baleful ugliness of Der Ewige Jude. This was not the first time that art was born of coercion. The last few seconds of Fascist joy may be seen through the bewildered smile of a small boy (Germany Year Zero).(7)

The last shot of Rio Escondido: the face of Maria Felix, the face of a dead woman whom the voice of the President of the Mexican Republic covers with glory. In dealing constantly with birth and death, political cinema acknowledges the flesh, and metamorphoses the holy word without difficulty. Unhappy film-makers of France who lack scenarios, how is it that you have not yet made films about the tax system, the death of Philippe Henriot,(8) the marvellous life of Danielle Casanova ?(9)

* As Brice Parain notes: ‘the sign forces us to see an object through its significance’. (10)

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Translator’s notes

Most of the films referred to in this article are Russian: The Rainbow (Mark Donskoi, 1944), Zoya (Leo Arnstam, 1944), Ivan the Terrible (Sergei Eisenstein, 1944-46), Michurin (Alexander Dovzhenko, 1947), The Young Guard (Sergei Gerasimov, 1947), The Fall of Berlin (Mikhail Chiaureli, 1949), and Battle of Stalingrad (Vladimir Petrov, 1950). Hitlerjunge Quex (Hans Steinhoff, 1 933) and Der Ewige Jude ( Fritz Hippler, 1940), both German, are two of the most notorious Nazi propaganda films, the former anti-communist, the latter anti-Semitic; while Leni Riefenstahl directed the equally notorious Triumph of the Will and the Berlin Olympics film of 1936. Kuhle Wampe, on the other hand, was notorious as the only German film of that time (1932) to be communist in inspiration. Written by Bertolt Brecht and Ernst Ottwalt, directed by Slatan Dudow, Kuhle Wampe (shown in the West as Whither Germany?) was an independent German production partly financed by the Russian company Mezhrabpom. Promptly banned on political grounds, it was subsequently passed subject to cuts. The odd film out in this political catalogue is Rio Escondido: a Mexican film directed by Emilio Fernandez in 1947, it is a heavy-breathing melodrama with Maria Felix piling on the histrionics as a schoolteacher who devotes her life to conquering illiteracy among the Indians.

(1) ‘Siegfried . . . Limoges’: A reference to Jean Giraudoux’s novel Siegfried et le Limousin (which he later turned into a play, Siegfried). It is about a French soldier (from Limoges) in the First World War who, wounded and amnesiac, is assumed by the Germans to be German and re-educated accordingly. Later, when his true identity is discovered, he is asked to choose between his two countries, France and Germany.

(2) ‘The beautiful bodies of twenty-year-olds . . . ‘: A line from Arthur Rimbaud’s poem, Les Soeurs de Charite, which Godard has put into the plural (in Rimbaud’s original it reads : ‘Le beau corps de vingt ans qui devrait aller nu’).

(3) ‘Hennione’: in Racine’s Andromaque. Hennione, loved by Orestes, is hopelessly in love with Pyrrhus, who loves Andromache, whose insistence on remaining faithful to the dead Hector sparks off the holocaust of the play.

(4) ‘ Rastignac . . . Julien Sorel ‘: The first is a character in Balzac’s Le Père Goriot, the second in Stendhal’s Le Rouge et le Noir.

(5) ‘Soviet economy plans’: A joke lost in translation, since the French for ‘shot’ is ‘plan’,

(6) ‘Georges Sorel’: French social philosopher ( 1847- 1922). Largely self-taught, he was a follower of the Anarchist philosophy of Proudhon and Bakunin, denying the concept of progress and instead advocating a ‘heroic conception of life’, At first on the Left as a champion of the Syndicalist cause, he later veered to the extreme right-wing nationalism of l’Action française. The Fascist movements in Germany and Italy were inspired by his system of a Corporate State, and by his idea of a heroic myth used to arouse public opinion.

(7) ‘ Germany Year Zero’: Roberto Rossellini’s 1948 film, Germania, Anno Zero, is set in the ruins of Berlin after the Second World War. The protagonist is a twelve-year-old boy who is driven by the chaos round him to delinquency, patricide, and finally suicide.

(8) ‘ Philippe Henriot’: Executed as a Nazi collaborator after the liberation of Paris in 1944. In the 1930s, as Oeputy for Bordeaux, Henriot had been one of the leading anti-Semitic witchhunters in the Stavisky affair; in the 1920s, at a time when the conflict between the Catholic militants (right wing) and anti-clericalists (left wing) had a distinct political bias, he was one of the chief spokesmen for the National Catholic Federation.

(9) ‘ Danielle Casanova’ : A heroine of the French Resistance during the Second World War.

(10) ‘Brice Parain’: A contemporary French philosopher, particularly concerned with problems of language, once described by Sartre as a man who is ‘word-sick and wants to be cured’, He later made a personal appearance in Vivre sa Vie as the philosopher who talks to Nana in the care about truth, error and the problems of linguistic communication .