By Jacques Rancière

Originally published as ‘Un cinéma des minorités (Retour d’un festival dédié à la frontière)’, Cahiers du cinema n° 605 (October 2005).

This year Douarnenez hosted the 26th edition of a festival which has from the outset dedicated itself to the theme of national minorities, this time focused on the Mexicans in the United States. This continuity is not without its problems. In a quarter of a century’s time, the cause of minorities has suffered its share of tribulations, from consensual integration to terrorist diabolization. The cause of militant – or simply political – cinema is not much better off. It has certainly made great efforts to escape from what it is always reproached for in advance: stereotypy and manichaeism. But the gaps intended to avoid manichaeism themselves constantly become fixed on stereotypes. This is evidenced in the cinema of Ken Loach, represented in Douarnenez by Bread and Roses, dealing with a strike of Chicano cleaning workers in Los Angeles. The too edified theme of the consciousness-raising of exploited workers is here carefully destabilized: on one hand, by the Woody Allen–like gesticulations of a syndicalist agitator coming straight from the universe of East side law schools, played by an actor, Adrien Brody, who is used to portray persons who are not at their place; on the other hand, by the human density conversely bestowed on the mother of the Chicana family who betrays the strikers. But this unsettling of stereotypes has itself become a recipe. The problem in fact concerns the politics of fiction as much as the militant good will. Mixing the correct proportions of the militant and the aberrant, comedy of manners and the fantastic: this is the principle of this programming which mixes, since half a century, documentary and fiction, Hollywood and independent cinema. But in a wider sense it is the problem of the cinema of today that wants to bear witness to its times.

Maybe that’s why the problematic theme of minority identity was displaced with a formal thematic, summarized in a title borrowed from Chantal Akerman, De L’autre Côté (From the other side). If the theme of minorities is stuck in the oscillation between stereotypes and counter-stereotypes, the theme of the other side allows to play freely with the literality or the metaphoricity of borders and crossings. If Aldrich’s El Perdido was included in the programme, it’s obviously not for the figuration of three Mexican guitar players or the crossing of the Rio Grande, but for the impossible encounter between Kirk Douglas and Carol Lynley, symbolizing the effacement of the borders between order and disorder, childhood and adulthood, dream and reality. The naked reality of the border wall, on the other hand, obstinately returns in several films, especially documentaries, notably this border which extends into the sea in Tijuana, all the while allowing children playing on the beach to gaze in from the other side. In Mickael Roth’s Aliens on Hope Street, the “aliens” of Los Angeles, these writers who blend English with Spanish at the same time as urban tumult blends into poetic wording, consider themselves shaped in their identity by the scar of this wall.

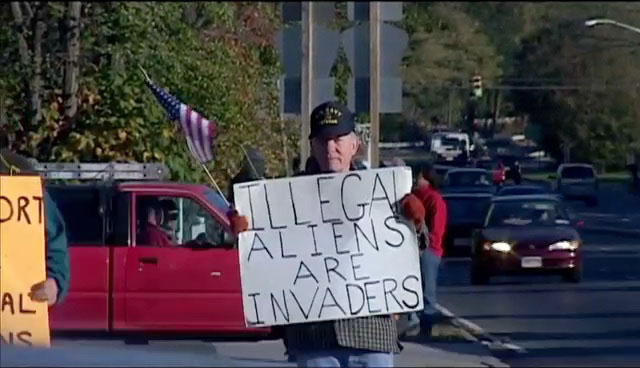

But the other side can simply be the opposite pavement where the residents of a small town in Long Island see the immigrants regrouping like a irreducible multiplicity, waiting for the cars of the contractors, or the house next door where an unknown number of them is living in group. “It’s not a problem of race, it’s a problem of density”, says one of the residents of Farmingville, interviewed by Carlos Sandoval and Catherine Tambine in the film with the same title. The merit of the filmmakers is that they have taken the thing literally. The coexistence of natives and immigrants is first of all a problem of population of spaces and respective positions of bodies. Giving space and time to these words on urban density and quality of life is also a way of connecting two spaces shaping American identity: the local assemblies giving over to the confrontation of ways of thinking and the streets giving over to the uniformity of ways of living. The otherness of the thousand five hundred Mexicans of Farmingville is also the strangeness of American democracy.

It is undoubtedly the advantage of the documentary form: not having to construct identities, looking for the right mixture of politics and non-politics, opening up to the multiplicity of arts by which everyone acknowledges being capable of creating his/her character and constructing with words a space to dispute communally; see its mise-en-scène displaced by the art of speakers and the art of presentation of bodies: in Chantal Akerman’s film, the enigmatic smile of the young man recounting the journey of those who died while crossing the desert; the flowered blouse of the old school teacher recounting the misery of the village; the restrained words of the letter read out loud by the clandestines to those hosting them in a Christmas decor; the gesture of the one looking for a paper napkin to dry his tears. The most effective politics is not one of portable cameras trying to stick close to the bodies of clandestines running in the night, towards the small vans where they will be piled up. It’s the one setting up flush to the wall, on the day when the cars pass by indifferently, the evening when children play base-ball, the night when the spotlights compose a fantastic ballet; the one confronting its silence with the words of those who, on one side, describe their stubborn journey in search for a “form of better life”, on the other side, confer their problems of density and environment. De l’autre Coté constructs the space of a modification of relations between those who speak and those who keep quiet. This modification could define the programme of a minority art. It is also a fairly good definition of politics.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Translated by Stoffel Debuysere (Please contact me if you can improve the translation).

In the context of the research project “Figures of Dissent (Cinema of Politics, Politics of Cinema)”

KASK / School of Arts