A dialogue between Pedro Costa and Thom Andersen on Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub, after a screening of Costa’s film ‘Où gît votre sourire enfoui?‘ (‘Where Does Your Hidden Smile Lie?‘), on 28 September 2006 at the Bijou Theater, on the campus of the California Institute of the Arts, Valencia, California. Originally published in Cinema Scope, issue 29, winter 2007.

Andersen: Your film on Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub is often described as a romantic comedy, the kind Stanley Cavell calls “a comedy of remarriage”. I think it’s sometimes compared to some of Hawks’ movies. The other day you mentioned The Marriage Circle (1924) by Lubitsch. Do you want to comment on the comedic aspects of the movie?

Costa: That’s a difficult way to start.

Andersen: You want to start another way?

Costa: Yeah. Because that involves a lot of personal relations between us. I understand very well what Jean-Marie is saying when he addresses me, because he’s really my master. I know there are some secrets that I cannot tell because it’s better to be private, to keep it secret. But I know there is a movement on Jean-Marie’s part in the film of giving himself, exposing himself and exposing his love story, as well as his knowledge and sensitivity, or sensibility. The way he described the first meeting with Danièle is, I think, the best example of what he did for me, and for you, of course, in the middle of this very, very hard work he was doing with a lot of tension in that room, a lot of, I would say, suffering – they wouldn’t like this kind of word – but yeah, let’s say work, tension. And so he had the braveness of doing this movement, of giving some wonderful fragments of their love story, which is personal, private. He had no reason to tell them. He was there just to talk about the editing of this film, cinema, his opinions, to share a bit with the students.

This is a way they found now – or I should say, someone found for them – to finish the films they do today. It is very difficult for them to continue working. One of their mottos is “this will be the last film.” They are always saying that. And it’s absolutely true, not only because they approach every film as the last one, the first and the last, but because to finance the films and to complete them is very, very difficult. I know now for instance – because I helped them a little bit in one of the movies they made recently – I know people now work absolutely for peanuts, as you say, with them. With a lot of pleasure, of course. I could tell you that my film on the Straubs costs as much as Sicilia! So they have this plan B, this escape plan to finish the films, which is going to this school in France, and in exchange for talking like this, about editing, about cinema, about what you’ve seen, they can edit the films and they are given a print. One print. I think that’s the only way they can do it. They’ve been doing this kind of seminar for the last four or five films, I think.

I was there from day one to the end. And as you see, it’s made chronologically. Thay start on the first scene, they end on the last. This lasted for one-and-a half months. So what was a bit ironic or symptomatic was that on day one there were 30 students, and on the last day there were three, one girl and two boys. So that’s very sad because it’s like a screening of one of their films. Everybody leaves.

Andersen: sometimes

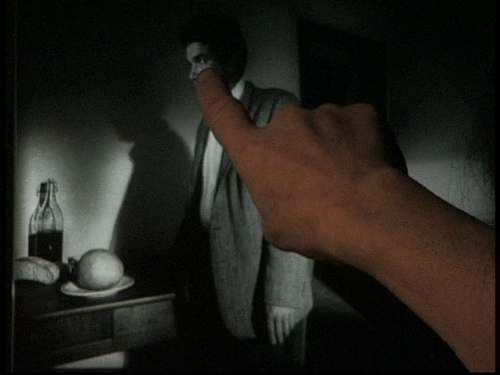

Costa: Sometimes. But the ones that stayed were there. There was this deal also that they were showing some of their films in the school’s cinema. I shot that, and I chose to have these two or three moments of those, let’s say, shows, for a simple because that’s the purpose of this series, Cinéma, de notre temps, which is a bit didactic. Also, it’s made to let you know what kind of films this man makes or that woman does. So it should have a didactic side to it. In the case of Jean-Marie and Danièle, it goes much deeper, I think, because for them cinema is not disconnected: it has to do with an attitude, a way of behaving every day. So there is a political way of being that had to be there also. So for me there is a very beautiful moment when Jean-Marie presents the Death of Empedocles (1987), and he shares this vision he has, this dream. This dream is more or less the same as that of this guy he’s talking about – the German poet Hölderlin. This Communist utopia. That has been something he’s been working on in films and his life with Danièle. And he’s probably the person who has worked this dream most deeply, in life and in art. So I had to have that. And the part at the end where he makes a summary of his life, his artistic life, and he says to the audience, “We started, it was difficult, but we enjoyed it, and we’ll keep going.” I felt that I should have those kinds of moments in the film because it wouldn’t be complete, without them.

Also, I wanted to destroy a little bit this common notion, this common cliché, that Straub is intellectual, difficult, hermetic, or Communist, Marxist, Maoist, terrorist – I don’t know what else. When I was young, it was impossible. You almost avoided going to see the films of these people, even the people that were their friends, like the Cahiers du Cinéma. I never agreed, and they don’t agree either – because we’ve talked about that – with those kinds of etiquettes and slogans. It’s like saying: don’t go see that. It creates indifference. It’s like denying this natural faculty that we all have of seeing and watching in liberty, in freedom. We’re free. So when this cultural thing begins, it’s like the beginning of indifference for me. It’s very violent, I think. It never stopped me from going to see their films, but I know that it frightened a lot of people. And perhaps some people saw their films and didn’t like them, I think, because of this other side. You have to know that is Hölderlin or Kafka or Schoenberg on the screen to like the Straubs. It’s not true. You just go there, and you hear something, you see something. If you like that, perhaps you can discover Schoenberg or Pavese. Culture means nothing to them, I think, culture in that sense. It’s really like Danièle says: it’s an effort in giving or approaching something. And then people discover things. So that was also one of the reasons why I accepted to do this films. It was to go against a lot of mainly French and American critics that didn’t help the films. I’m not saying that was the worst that happened to them. Far from it. But it didn’t help. So i think you have a light comedy.

Andersen: But also you were saying that for you the greatest films are the saddest films. And the ending of this film is… I don’t know if “sad” is the word, but “poignant”. They come into the theatre at the end of a screening…

Costa: This film is the impossible dream of every filmmaker because it’s a love story that works, that ends well. It’s probably the last chance I had of doing a film that has a happy ending. I always see that as a happy ending. He’s tired. There’s Beethoven regaining a bit of life, as he said, just for a moment perhaps. But he has his lighter. You see the light. And you know Danièle is behind him. She’s upstairs somewhere, always. So this is exactly like lubitsch. It’s a dream. How can you do something like Lubitsch? I did it once. Now it’s over. I will go on to do sad movies again. But this is not a sad movie, I think.

Andersen: Well, for me, when you’re standing or you’re sitting outside an auditorium in which people are watching a movie you’ve made, there’s a loneliness you feel that is a kind of special loneliness because you know that the way other people experience a movie you’ve made is something you can’t share because your relationship to it has to be different from that of everyone else. So I always feel, even if people like the movie, I always feel a kind a special isolation, which for me is kind of sad.

Costa: Snap out of it.

Andersen: All right.

Costa: Of course it is sad. It is always like this to people that work so hard and try to discover something new. What I found very nice was that everything confirmed all the expectations I had. I knew them a little bit before I did this film, but just from festivals and things like that. It was a very difficult decision for me to do this film because it has been in development for years. Three people tried to make it and failed. Janine Bazin and André Labarthe suggested me for this film because they knew that I was a fan, a guy that always, always, in interviews spoke about the Straubs. So when they asked me if I would like to do it, I said, “Yeah, I have to think because it’s something that is a bit scary.” Not because of them. That I think I could deal with. But what to do? And how? That was difficult. So it was a long story. I went to see them in Rome where they live. I had no idea what to say to them. So we spent one hour, me and Jean-Marie, in silence in a bar. And after an hour, he said, “So, what about this film?” And I said “I think I can make it.” And he said, “What’s it going to be?” And I said, “I’d probably like to film this editing you are going to do in France.” And then I remember he said, “That’s impossible, you can’t see that, it’s impossible to translate the image and sound.” And I said, “Yeah, perhaps.” But I had this experience of the other film, In Vanda’s Room, and sometimes in Vanda’s room, I had this impression that I was in this room and it became something else and the walls were moving and Vanda speaking, ad time and space were just there in front of me, and I was much more in control of all that than in the normal shooting, and so I was very, very sure of what I was seeing and hearing. And I told him about that, and he said, “I don’t think so, but if you don’t bother Danièle, okay, let’s try.”

Then he told me something very funny. He said, “But don’t forget that you will never, never find any artistic secrets. There are no secrets behind us.” I think that was the problem of all the projects before. They wanted how these crazy people do this kind of stuff. And so the editing work was for me the answer, to be close to this nonexisting secret. It’s just about work. So we started, and as Danièle said, it was just about confidence, trust. Little by little, I think they saw I was doing a very hard job myself, and Matthieu Imbert, who was doing the sound. And, of course, everything was confirmed. What I thought or suspected was true. Fortunately, of all the great artists I’ve met, mostly people that I loved very much when I was starting young and just dreaming about them and imagining things, now that I know them, it’s like there’s a reason for me to have loved them before. There was a poetic reason. So I was right. And that is a strong feeling to have. Knowing that you were right doesn’t matter that much, but for your art, it’s important. Sometimes for life. So they were very, very cooperative and generous, as you see, and they were always there.

Andersen: Maybe there aren’t any secrets revealed in the movie, but there are lessons, right? About patience, concentration, reduction, about where form comes from, how you can make a cut. I think for someone who’s interested in how you make movies, it’s a very useful film, even if you don’t agree with everything they say, or with their methods. I’ve always thought a lot of their ideas, which sometimes seem specialized and esoteric, actually apply to other kinds of filmmaking as well.

I could provide one example from my experience (Andersen had a small role in Class relations (1984)). Quite often the acting in their movies is, you might say, peculiar by Hollywood standards, or you could say Brechtian, as they have. There’s actually a quotation from Brecht in their films about the acting style. Something to the effect that the actor should tell the truth, he’s quoting. I recall one time when we were working on Class Relations, in 1983, Danièle said to us as we were working on a scene: “Don’t try to act until you have the lines in your blood.” I think all actors should follow this rule. It would prevent a lot of bad acting. But actors begin to act before they know the lines, so they get into bad habits, which repeat and repreduce themselves when they deliver the lines.

Question: Can I ask Thom about his experience in working with the pair? How many takes did you do?

Andersen: Twenty

Question: And what did they tell you between takes?

Andersen: Oh, Danièle said: “Don’t be lazy with your eyes.” That’s all I can remember. In your film, they said something about Christian Heinisch, the star of Class Relations, this young kid who was extremely bright, and because he’s been working with them for so long on this movie, three months or so, he understood what they were doing really well. Don’t they say he was the only actor they ever worked with who knew how to look?

Another story may relate to something Pedro was saying. This was a big production for them, it was a very long shooting schedule, three months or something. Most of the film was shot in Hamburg, but at the end they made one trip to the US, with two or three of the actors and the crew. But the crew was only six or seven people. There were two sound people, a kind of line producer, the director of photography, his assistant, maybe two lighting guys.

But the whole film was made for $250.000, shot in 35mm black and white. They did 20 or 30 takes of each shot. So they said, “You know, in a way we’re the richest filmmakers in the world.” Because they had found a way of working which enabled them to do what needed to be done, to do as many takes as they thought were necessary, by simplifying other aspects of the production. It makes a difference: when you have a crew of six people, you can be a director; when you have a crew of a hundred, catering trucks and all this, you’re not really an artist, you’re a general commanding an army, which is a different kind of work. Not necessarily evil work, just different. And it was like a close-knit family, everybody went to dinner at the same restaurant, everyone stayed at the same hotel and drank in the hotel bar after dinner. Well, Danièle and Jean-Marie didn’t hang out in the bar. They would edit.

What else can I say? Oh, one thing: you can make what you will of it, but I was impressed. I came a little earlier than was necessary for the scenes that I was involved in, and I watched them film for a while. There was this one location, and they filmed for the day with the actors and the crew. It happened to be the last day at this location, and everybody left (for the day), all the actors and the whole crew, but they stayed behind to clean up: they actually got down on their hands and knees and swabbed the floor of the location where they were working, so the place would be left the way they found it. So while everyone else was going out to dinner, they were doing the work that on any other movie would be done by the lowliest members of the crew.

Costa: Jean-Marie also said to me that his work as a director was much more about picking up cigarette butts than directing actors.

Question: You mentioned that in some ways you made this movie in response to a certain strain of criticism, both in France and America. Not being familiar with that body of literature, I was wondering if you could talk about that body of criticism?

Costa: go to your library.

Andersen: If you read French.

Costa: There was a moment, when I was 20 or so, there were two main forces for a person who liked cinema: Godard and Straub. And it was a very strong moment. In my case, when I saw the films, I was much closer to Straub than Godard. I still am. For me they are much closer to my beliefs on sensuality, violence, or tenderness. Perhaps it’s just really that there’s something more crude and raw, without camouflage, you know. That was what I liked about Straub. Actions to me found correspondence in Straub, not in Godard. Godard seemed very old to me, suddenly, when I saw all of Straub’s films. They were the fastest, the most furious, the most beautiful, sensual, ancient, modern. There was no doubt for me. The problem was convincing the others.

So I had these texts that sometimes didn’t help. Some were good, but let’s say the textual atmosphere around Straub was a bit… it didn’t talk well about this principle of sensuality in cinema. And that’s what I wanted to remember in this film, the feeling when I was young. They say it all the time. When they say, “it’s not true that in our films there is no psychology,” they are talking about that. They’re saying if you work well, you will have something. And they don’t avoid the words “emotion” or “tension.” And you can see how film is a movement, it’s a tension that you have to keep going in this editing room until the end, and it’s very, very difficult to maintian this tension, because it’s a tension you will probably have in life also if you do this kind of work. And another problem is that this tension is not bearable. It would be good to have this tension every day, every second, but it’s not possible. They perhaps are the people that go… they go very far in this. When I say “tension,” I could say “intense,” but no, it’s tension, a nervous sensibility, an attention to things, the kinds of details you see in the film. You have to be really, really attentive to see these kinds of things. You cannot maintain that all your life every day, it’s exhausting. But everybody should live that in that kind of way. That’s what they tell us, I think. Everybody should be as tense as a Bach composition – and let’s not say “complicated” or “difficult.” Let’s say “tense,” it’s much more simple, I think.

Question: So is that the reason Straub is referred to more than Huillet, because he was the primary author of these texts? Did he engage in these intellectual debates with Godard?

Costa: The essays are essays that people wrote about them, everything that people wrote in newspapers and magazines, some schools. Sometimes they said “Marxists,” they said “Maoists,” they said “terorists,” they said “formalists,” “Eisensteinians,” “Fordians,” It could be everything and the opposite. What I didn’t like was that people like you, people who don’t know the Straubs even today, can be blinded by these kind of things. So let’s see the films first, and then you can read, great texts on the Straubs – and I’ll tell you a lot of them – and then you can perhaps forget these “Maoist-Marxist-terrorist-hard intellectual” labels.

Andersen: Or maybe you could say there was a time when their films got reduced to being debating points in intellectual arguments. The films became objects to theorize about, and the theorizing wasn’t good enough. But there was another question she was posing: while they are equal collaborators, why do people often talk more about Jean-Marie than about Danièle?

Costa: You know as much about that as I do. I think because he’s the man – that’s point one – and a filmmaker is a man. I think also because she likes to be where she is. There is always this show-off in Jean-Marie. Jean-Marie is really an entertainer, let’s say. He would have liked to be the James Dean of the north of France when he was young, but he’s a genius, so… Danièle says you can be a genius for them, but you’re a distaster at home. He’s the boy, like you see. And Danièle is the woman: she takes care of him. They have been editing like you saw since the beginning, but in the first two films, the credits say, “Directed by Jean-Marie Straub,” and Danièle is the editor, or the producer sometimes. Then it changed to “Directed by Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet”, and now it has changed to “A film by Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub.”

Andersen: I think another thing is if you listen to them talk, or read the transcript of one of their interviews, Jean-Marie will go on for 20 minutes, and then Danièle will say one sentence that sums everything up. He talks a lot, but in a certain way she has more to say. She’ll cut to the chase, as it were, and say what he was trying to say over those 20 minutes. You can see it in the texts of the interviews that have been published.

Costa: And she corrects a lot of his misspellings and dates. When he says, “1914,” she says, “It’s ’24.” Or, “It’s not them, it’s they” – these kind of things; But seeing them work like I have, you can see more of Jean-Marie on the set. He’s more agitated, more behind the camera – it’s his job to be behind the camera, whereas she’s more of an art director, and likes to be with the actors.

Andersen: In my experience, on the set, Jean-Marie works on the image, and Danièle is directing the actors and working with the sound.

Costa: But she also does the clothing and the props, everything else. But I think a part of this very beautiful movement that their films have comes from her. This rhythmic fury that they have comes from her, because she’s so controlled. It’s like Moses and Aaron (1975): she’s the mouth of Jean-Marie in the film. She has this nervousness in he cutting, but she’s very calm and controlled. She’s tense too, but more controlled than Jean-Marie, who can be hyper-sentimental, and sometimes very melancholy also. So her work is to pull hum out of that dark place, saying, “Shut up,” or like they say, he’s always talking rubbish, and she says, “There’s a way of not talking rubbish in life: just shut up.” But it’s a collective work, it’s a duel, it’s not one person. It has never been, I think. Because they love each other so.

Danièle Huillet passed away 11 days after this dialogue took place, on October 9, 2006.