By Serge Daney

Originally published as ‘La remise en scène’ in Cahiers du cinéma 268 (July 1976).

Deceitful intent and despicable procedure

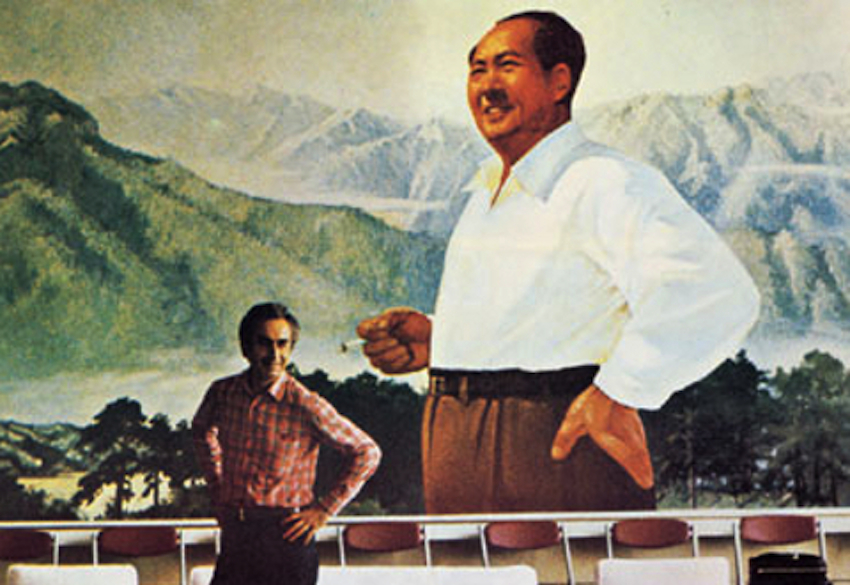

It’s under this title that the Renmin Ribao (“The People’s Daily”) trashed Antonioni’s Chung Kuo. The argumentation was rather strange. Judge by yourselves (it’s about the Tiananmen Square).“The film doesn’t provide any general view of this place and removes all majesty from the Tiananmen gate, which the Chinese people hold so dearly. Conversely the author doesn’t save any pellicule to film small groups of people on the square, sometimes from a distance, at other times up close; sometimes up front, other times from the back; here a swarm of faces, there an mesh of feet. He deliberately turns the Tiananmen square into a messy fair. Doesn’t he have the intent to insult our great homeland?” (To this false question, the answer is evidently: yes)

Two reproaches then: 1. By way of an exaggerated multiplication of shots and angles, Antonioni cuts as he pleases (without respect, denigrating, insulting). 2. He doesn’t reproduce the official image, which is supposed to be emblematic of the place “which the Chinese people hold so dearly”, its “brand image”. He does the same when he films the Nankin bridge: “While filming the great Nankin bridge on the Yangtsé, this magnificent modern bridge, he has deliberately chosen very bad angles, giving the impression that it’s crooked and unstable.” In other words: every image that deviates from the brand image is supposedly slanderous. Or: not filmed= denied, denied= contended.

There are cut up images that are supposed to be whole, and there are images that are supposed to be there but are missing. Third reproach: “In regards to the choices he made while filming and editing, he has hardly filmed the good, new and progressist images, and if he has filmed them it was rather for show and to cut them out afterwards.” In other words: the “good, new and progressist images” are not to be constructed but are already there, already given and only to be reproduced. Isn’t the Renmin Ribao contributor assigning a mission to cinema: re-mettre en scène?

Typage and natural, natural and typage

So far for the Renmin Ribao’s argumentation (definitely strange). Let’s get back to Europe. For those interested in Chinese politics (and not only in China as dream or utopia, model or challenge), Chung Kuo wasn’t a very satisfactory film. We couldn’t get rid of the impression that we were assisting in the mute tribulations of Chinese extras in China, under the eye of a great skeptical but nevertheless attentive esthetician who concludes from all this, a bit brisk, the impossibility of understanding anything at all of the mysteries that were shown to him. He refused to affix his signature to the already constituted images (the “good images”) that were expected to be reproduced (Chinese naivety? Pro-Chinese naivety?). Worse: he got even more attached to the images that were advised against or forbidden: an official building, a military boat, a free market in open country. The Chinese didn’t seem to be aware that the only image that marks or “brands” here in the West, is that which is won out on something.

For us (at Cahiers), there was something else at stake in the criticism on Chung Kuo. It provided us with a particularly convenient occasion to restate our mistrust of naturalism. To all those who were bewildered by this slice of life, it sufficed to say: in cinema, there is not only encounter, naturalness, “as if”. There is no image that slyly (naturalism) or explicitly (publicity) wants to become a brand image, that is to say of the congealed, blocked, repressed. And we added: the sly typage welling up from Chun Kuo is not without ulterior motives or malicious intent. We don’t have great merit in being right: Antonioni himself doesn’t hide that he avoids what he does not understand or consider: Chinese politics.

But confronted with the arguments made by the author (anonymous of course) of “Deceitful intent and despicable procedure”, we were also divested. How can one reproach Antonioni of not having filmed the Tiananmen square from an official angle? And why infer that these shots would insult the Chinese people, while in France it’s exactly those shots that do not hold any denigration or slander? It’s almost the opposite: for a progressist audience (those to whom the film is aimed, evidently not the Franco-Chinese friends), a human, close, non majestic image, not resembling a postcard of Tiananmen, was something positive. Where do paradoxes like this one come from (from the Renmin Ribao): “But Antonioni shows the Chinese people as an ignorant and stupid crowd, cut off from the world, with sad and worried faces, without energy or hygiene, loving to drink and eat, in short a grotesque horde. “ And in Libération we could read, written by Philippe Sollers, at text on the calmness, the nonchalance, the lack of hysteria of the Chinese crowd.

We also wanted to tell the Chinese exactly the contrary of what was being said to the readers of Libération and Cahiers: there is not only typage, the exemplary, a film is not only an encoding, a shot is not completely determined by the cause it serves, the image resists. The little of the real it encloses doesn’t let itself be reduced like that. There is always something that remains.

Funny debate which was already about the here and the elsewhere. Here (Paris, end of 1973): release of an Antonioni film on China. Question: what does an image hide? What is its out-of-frame? Elsewhere (China, beginning of ’74): violent debate on western art and “musique sans titre”. Question: what does an image show? What is there in the frame? Here: repression of the “prise de vues”, of the political dimension of the shooting, in favor of of the fetichism of the image taken, won (of the scoop), according to the double criterium of rarity (China) and truth (the eye of the master: Antonioni). Elsewhere: repression of the image in favor of a normalization of the “good image” which is nothing but a “re-prise” of the déja-vu. Here: tracking down the mise-en-scene under the natural. Elsewhere: tracking down the natural under the re-mise-en-scène. Cross-over or short-circuit?

Ambivalence or Amphibology

There’s a scene which the Renmin Ribao contributor didn’t mention: the opening scene showing a childbirth (Caesarian, under acupuncture). Suppose that Antonioni wasn’t the anti-Chinese monster in lack of defamatory images. In that case a question comes up: which images to take back from China that can satisfy the Chinese authorities (those who invited him) and can show the western audience (the only ones who will see the film) something of China, something impressive, something that they don’t know or don’t know well. The cesarian is one response.

In fact, it plays out on two levels. For the Chinese, it illustrates the success of popular medicine: success of acupuncture, success of the ideology “in service of the people” in medicine. Of this image (a birth “with eyes open”), the Chinese have reason to be proud. It’s evidence in their favor.

For us as well this image plays out favorably, yet for different reasons: it shows – better than all discourse – that the relationship the Chinese have with the body is at the very least very different than the one that exists in a society such as ours. The fear of disembowelment, of in- and outside, of shame and fault, is missing here. It’s about something else. About what? We don’t know, but it’s enough that the question is asked. This image, for us, is revelatory. It touches upon our truth.

So here’s a series of shots that is twofold positive, but in two different areas. For them and for us. It satisfies two audiences who will never meet, except by virtue of this film. It forbids the western spectators to put themselves where they are not (in pro-China for example), it does not permit the Chinese to put themselves where they are not (in the throes of the Christian body). It keeps its distance and in doing that, it makes visible.

We see that a militant discourse would object to this double scene. What is important, it would say, is not that these shots play out positively in two areas that don’t know about each other, it’s the fact that because of this mediation these two areas, the Chinese and the French one, have started communicating with one another.

We should know by now that it’s not people who communicate but rather objects (statements, images) that communicate by themselves. In putting too much trust in communication, we risk being disappointed, like we were three years after Chung Kuo when noticing that Joris Ivens, despite his talent, only provoked smiles with Yukong. At least Antonioni is a smuggler, not “here”, not “elsewhere”, but between brackets, protected by them, without anchor, exposed. Exposed to the utopia, to the non-place. Moreover, that’s what worries and delights him since forever: cinema as affirmation of distance, however small. In this scene in The Passenger in which the old African chieftain grabs the camera and films Jack Nicholson, one can see quite clearly what is at issue: the sudden possibility of a reversibility, of the camera passing without a word from hand to hand to the great confusion of the scene and the actors. This, in China, was simply impossible.

The pose (keep smiling)

Someone is being filmed? There are several approaches:

1. The filming happens within the framework of the industry of cinema. It is then symbolically covered by the type of contract (wage, one-off fee, benefits participation, unpaid) agreed between the production and the actors. In the name of this contract, the filmmaker will be able to demand a certain acting or performance.

2. The filming happens within the loose framework of a documentary, of a socio or ethno-logical essay, or of an investigation. Most often, actors do not have the capacity, total or relative, of controlling, technically or intellectually, the operations to which they lend their bodies and voices. We then enter the domain of morals and risk: to film those for whom there exists no reversibility, no chance of becoming themselves “filmeurs”, no possibility of anticipating the image which will be made of them, no hold on the image. Mad people, children, primitives, the excluded, filmed without hope (for them) of a reply, filmed “for their own good” or for the sake of science or scandal: exoticism, philanthropy, horror.

3. There is a third type of situation (the one that interests us here): when the filming is done by a filmmaker or a crew who have decided to put their camera and their know-how at the service of. Of a people, of a cause, of a fight. In these conditions, the non-reversibility has other causes (under-development, lack of equipment, need for foreign help) , but generates new kinds of problems.

We know that a people in struggle is led to make an image of this struggle, a “good” image. Every extended struggle makes itself a brand image, a flag, a symbol regarding its identity, so regarding itself (because it always starts with the negation of this identity). Every image is always proof, a constatation, a piece of evidence. And to obtain this image one has to pose, and make pose. The Renmin Ribao reproached Antonioni to have cut, not having filmed a “general shot”, to have destroyed the pose. We are in the heart of the problem: how to respect this pose? And also: how not to respect it?

It’s an old question. Just like Joris Ivens’ response: “In every place we had to struggle to conquer our liberty. The natural tendency of people is to show only the positive aspect of things, to beautify reality. Is is a problem, I think, that I’ve encountered everywhere in the world. When receiving a guest, we clean the table and do the dishes. All the more so when the guest arrives with a camera.”

The common part

The same question is asked to the collective that has made L’Olivier. Danièle Dubroux: “In the children’s camps, what interested us was to show the relations between them, how they handled themselves, autonomously, their life, while doing the dishes, taking care of the plantations and the sheep… But they didn’t understand at all why we were interested in all that and the leader made them put everything in order especially for us.” It’s what Serge Le Peron formulated under the guise of a question-program “What is the common part of two systems of questions?” The film is taken up in a real four corners game. On one hand the one being filmed and their personal issues. On the other the ones filming and their personal dealings. But, behind the ones filming, there is also the question of knowing what effect these images will have on their audience and behind the ones being filmed, of what they imagine and what they hope from this effect that they don’t know. Example: “the Fedayeen were completely dumbstruck when we told them that this image they were showing of themselves, that of people taking up arms, is an image that, here, shows them like madmen, like people who only think about death and suicide, crazy, insane people.. While there, they were completely disarmed, if we could say so, in front of this possible becoming of their images, of these images of them in arms.”

Because, supposing that there are images that actually gratify this four corners game, it doesn’t mean that they would be the most clarifying or even the most useful. It is doubtful that the search for average images, formation-images of compromise defined by the sole fact that they don’t upset anyone, produces anything other than in-decidability, all obscurity and softness. An image can exist in various areas but it can only bear one point of view.

And yet, Ivens and Loridan: “These images, it’s a mixture of our presence and their reality. There is a dialectics between the two.” Strange dialectics according to which the terms of contradiction cannot be assigned. Mixture muddles while dialectics unites contradictorily, unites to divide, combines to disconnect.

“Our presence and their reality”. Making cinema directly based on a coded reality, is what characterizes ethnological cinema. In the case of China, the code has a name: politics. As its name indicates, socialism aims for socialization of relations between people. It makes them enter (mostly by force) the apparatus where individuals think and live the exercise of power collectively and “unconsciously”. By them and on them. Who doesn’t notice that we are already talking about cinema? The “cinema” that makes up a society, the postures that it takes in order to save face?

A camera and a microphone that are naively connected to the Chinese reality necessarily encounter this social pre-mise en scène. Either it renews it (to make it look spontaneous) or it makes it forget it for a while (but then, one has to cut it up). Naturalism is a technique that renews something that pre-exists it: the society as it is is already a mise-en-scène. To work on this given, break this pre-mise en scène, make it visible as it is, is always an courageous, difficult and unpopular undertaking. Realism is always to be won.

The duettists in question

In How Yukong Moved the Mountains, the most interesting episode, according to me, is the one taking place in the generator factory in Shanghai. Why? Because at the moment when Ivens and Loridan are in this factory, something happens that obliges them to leave their first idea behind and adopt another. The film becomes a report on an event that shakes up the factory: dissatisfaction of the workers, campaign of dazibaos, leaders being criticized, meetings etc. Suddenly there is a necessity for the filmmakers to stick to this fiction, to not cheat with it, to respect time and space. Necessity to do what they don’t do anywhere else in their film-flow: to make the masters of discourse come back to the screen at a time when these discourses have touched the fire of the real. In cinema, as in life, we can only take seriously what happens at least twice: for example the two criticized leaders (the duettists) of the generator factory.

What strikes us is that, from the beginning to the end of the film (before and after being criticized), they hold on to the same discourse, which all of the sudden sounds more and more hollow. Discourse without surprise: it is said that one shouldn’t go against the masses, accept their criticism, that it enriches, makes one better etc. If nothing had happened in this factory, this discourse would have played a accompanying role to an “open door” operation. But because we have had the time to witness them sound hollow, it makes us to see what other films seem to want to hide: that in China, more than elsewhere, discourse is above all not to be taken for what it says but for what it constitutes as a political practice that is more diffuse, more crafty, more complex, through which, in low as as in high places, power plays out.

The problem is not so much to know if the people are sincere or not than to encircle the articulation between this or that individual (a body and a singular voice, even if the discourse is stereotypical) and the collective discourse, the rhetorics for all purposes. What does it mean? What does he want when he talks? Or when he shuts up? Where is the accent of truth in what he says? Or, as they say in china, in “waving the red flag to attack the red flag”?

Roland Barthes, in a short text (‘Alors, La Chine?’) has seen this fundamental aspect of the relation between the Chinese and their discourse: circulation of power in the fact of power circulating speech and thus getting rid of it: “In fact, every discourse seems to progress by means of commonplaces (“topoi” and clichés), analogous to the sub-programs known in cybernetics as “bricks”. What, no liberty? Yes, under the theoretical crust, the text fuses (desire, intelligence, work, struggle, all that divides, bursts, exceeds). First of all, these clichés, everyone combines them differently, not only according to an esthetical project of originality, but under the more or less vivacious pressure of his political conscience (using the same code, what difference is there between the solidified discourse of this responsable of a popular commune and the vivacious, precise, topical analysis, of this shipyard worker in Shanghai).”

The important phrase here is “using the same code.” We know (it’s enough to read Pékin-Information) that the most bitter, violent ideological and political struggles speak the same language, they speak from the inside of a limited body of statements that function like so many cards (statement-trumps, statement-masters) in games that are always renewed. Hence the difficulty in recognizing the adversary. That is why Ivens can naively say “no-one says openly: I am a reactionary”.

Hence also the completely particular use that the Chinese make of brackets. Inside a discourse, the brackets never attest to the presence of another (system of quotes). Brackets in China are essentially defamatory. They constitute a double operation

1. To translate. Translate plainly (in the common code) what the other has never said but is supposed to have thought. Example: someone is supposed to have defended the thesis (evidently unsayable) that “the bourgeoise does some good.”

2. To put on the side. Brackets mark an isolation of bad discourse, designating it as defamation.

It’s because Ivens and Loridan have been the first to base their film on the words of the Chinese, that we are entitled to make remarks and reservations about their film. They relate to a decisive point that we can approach in different ways: discourse/power, statement/enunciation.

How to understand something of power, Chinese or otherwise?

How to film brackets?

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Translated by Stoffel Debuysere (Please contact me if you can improve the translations).

In the context of the research project “Figures of Dissent (Cinema of Politics, Politics of Cinema)”

KASK / School of Arts