Benjamin Godsill on Joy Garnett‘s ‘Kill Box’ (2001):

“Thanks to digital imaging, representations of violent conflict are often cleansed of real violence to real bodies: night vision, GPS, laser-guided bombs, and satellite imagery replace images of the violent destruction of actual bodies. Amid the actual obliteration of real bodies, war is waged on the level of the virtual and visual. As Retort formulates, the disconnection of images from systems of meaning-making increases their powers of social control; images acquire the ability to inscribe ideologies, ways of seeing the world, and viewpoints onto subjects when the gulf between the actual and the representation widens. With this growth, the ideological formulations supporting the construction, editing, broadcast, and reception of images increase in agency, as these functions connect image and event.

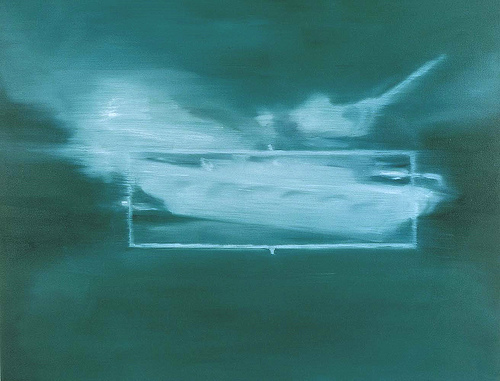

Joy Garnett’s painting Kill Box (2001) acts to deconstruct the hegemonic links between image and event. Garnett remediates one of the many techno-fetishist visual representations of the first Gulf War, hand-painting a tank in the digital target area–or kill box–that (presumably) a pilot has used to launch the missile seen blowing it apart. Garnett’s low-res style and palette loosely recalls the electronic green and ghostly white of the night vision technologies used by American forces in that conflict, whose images were then broadcast worldwide to signify American technological superiority. Representations of the Gulf War (a conflict that relied on digital technologies for both its execution and for the live feed of its images on global news) were overwhelmingly like the one in Kill Box. They were rendered from the point of view of machines that were designed and used to harm bodies, their night vision and infra-red points of view incapable of representing real physical bodies being destroyed yet masterful at creating cleansed, video-game-like war images to be beamed into living rooms…”

This works reminds me of some recent exhibited paintings by Luc Tuymans (Against the Day expo), ‘sniper’ and ‘bridge’, so-called ‘authentic falsifications’ of war images he found online.

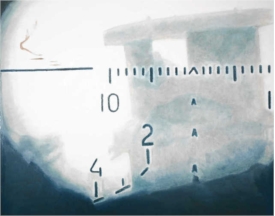

“Sniper is the fabrication of a meta-reality. It is the instant image of a real hit from a sharpshooter at the moment of striking his target in Bagdad. By pure coincidence, while surfing the web I came across this image that was later deleted and replaced by simulated computer games bearing the same title. The intention of this work is to fully revert back to the idea of the impact, and the immediacy; here, the view is diverted to the idea of the deed”. About ‘bridge’: “Like in Sniper, there is also a limited field of vision here, or how an access route becomes visible by a night watchman: a sort of tunnel vision where only the shining parts, the headlights of oncoming cars, result in blind spots; distance and speed become abstracted.”

A quote from an interview with Art World: “the image clearly goes to the ground, spiraling down. The show presents the idea of an end, showing things as raw material, dispersed and disjointed, simultaneously offering more and more propositions, but basically going nowhere. It is the world as we know it.”

Katrin Kaschadt on Thomas Ruff’s night photographs

“Thomas Ruff first exhibited the large-sized photographs of his Night series in 1992 at documenta IX. Up until 1995 about 40 pictures followed each depicting a different location. The serial treatment but also the large format both feature in Ruff’s previous works, his Portraits, Houses, Stars or Newspaper Portraits. Moreover, the topic ‘architecture’ emerges several years earlier – wholly in the tradition of his teachers Bernd and Hilla Becher. What makes the night photos different is Ruff’s employment of a new, unusual method which relies on the so-called ‘available-light amplifier’. The infra-red low-level light device enables the human eye to detect objects in intense darkness by amplifying the available light electrons which are normally insufficient to allow this. In other words, the shots depict what would normally be invisible to the eye.

By using an optical device which became known through its use in the Gulf War, Ruff stirs memories of the green pictures shown in news reports – not only evoking the military context and the specific historical event, but also the special media dimension particular to this war. This was the first time in history that the media was supplied with censored photographs of the theater of war on such a scale. Since the images on the computer screens of the military decision-makers are identical to those on the domestic TV screen, the actual events coincide with their presentation by the media: The viewer is directly confronted with the events presented to him/her. Yet what might have constituted an essential instrument to soldiers in the war, appears to the viewer in his/her living room as mere ‘second-hand reality’ prepared by the media; it is a means of satisfying his/her curiosity. Consequently, the night scene becomes a critical statement on the voyeurism of the Western TV viewer.

That said, Ruff does not show any pictures from the Gulf War but separates the technology from its war context by employing the infra-red device in city scenes set in his native Düsseldorf. Nevertheless, the original military context is transferred to the new environment. The green cast combined with the slight, foggy blur as well as the focus on the illuminated, usually central picture section transform the familiar scenes to suspicious locations of strategic military importance. The medium reveals itself to be a vehicle of interpretation..”