Figures of Dissent: Thomas Harlan

Programme 1: 16 February 2012 19:00, KASKcinema, Gent.

Programme 2: Courtisane Festival (21 – 25 March 2012)

introduced by Stoffel Debuysere

“My works don’t tell political stories. They rather document a political alertness, a clairaudience for certain constellations. My films, each for themselves, are generally useless for the purpose of a position or theory.”

– Thomas Harlan

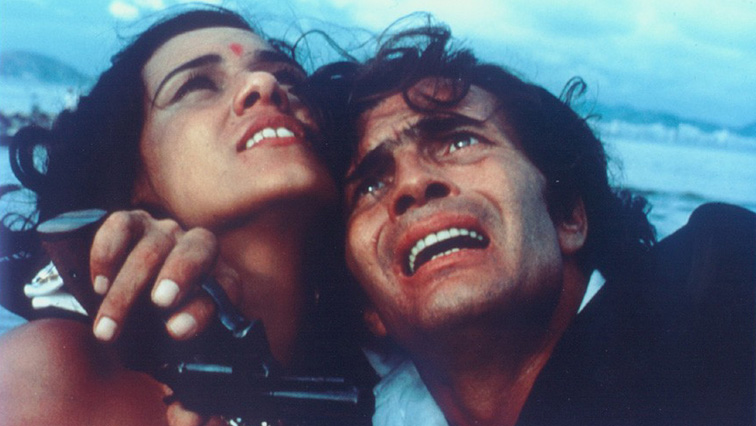

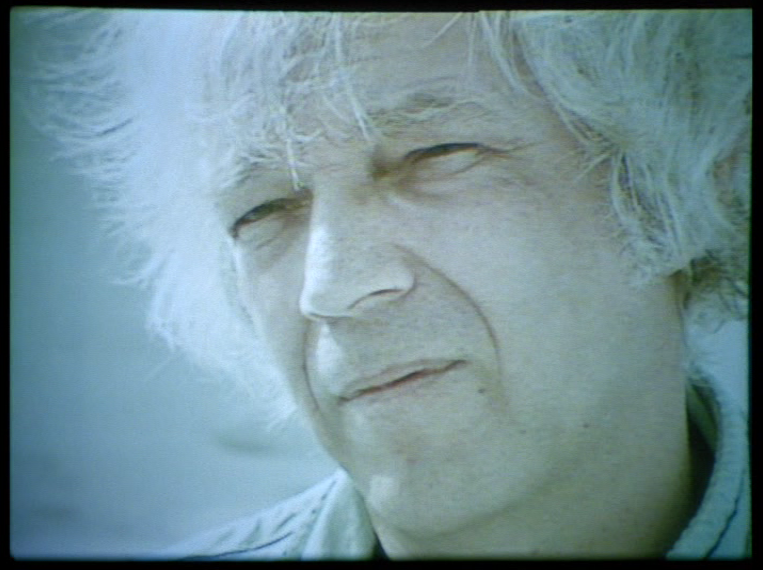

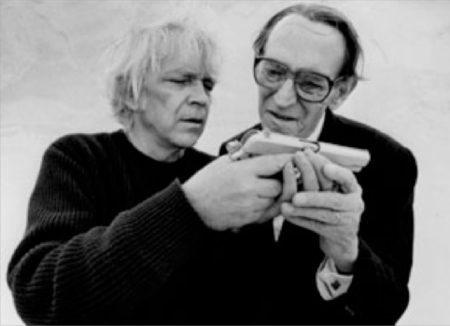

“I am the son of my parents. That is a disaster. It has determined me”, declares writer, playwright and filmmaker Thomas Harlan (1929-2010) in the interview book ‘Hitler war meine Mitgift’. Harlan, who grew up in Nazi-Germany, once shared a table with Adolf Hitler, accompanied by both of his parents, actress Hilde Körber and filmmaker Veit Harlan, the director of the infamous anti-Semitic propaganda film Jud Süß. It is a heritage that he could never get rid of: the appalled son would take upon himself the sins of his repentless father. His whole life Harlan would strive for truth as the only possible justice: he spent years in the Polish archives, looking for proofs of German war crimes; in Rome he joined the radical leftist group “La Lotta Continue” and travelled to wherever the spirit of revolt and revolution emerged. In 1975 Harlan was in Portugal where, in the aftermath of the Carnation Revolution, various movements of resistance and initiatives of land occupation were developing. That is where he shot his first film, a documentary about the occupation of the Torre Bela estate, which according to critic Serge Daney represents a condensation of “all the key ideas – materialised, embodied – of political and theoretical leftism from the past decade”. His following film project started as a reaction to the “German Autumn” of 1977. Wundkanal explores the relation between the events in the Stammheim prison, where several members of the RAF died in suspicious circumstances, and the logic of Nazi terror. The shooting of the film, in which war criminal Alfred Filbert played a hardly fictionalized version of himself, appears in Robert Kramer’s documentary Notre Nazi, revealing a staggering portrait of a filmmaker who, in an attempt to come to terms with his past, takes on the methods of the enemy and in doing so becomes his own worst enemy; and thus an old sin is replaced by a new one.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

PROGRAMME 1

16 February 2012 19:00, KASKcinema, Gent. A Courtisane programme.

Thomas Harlan

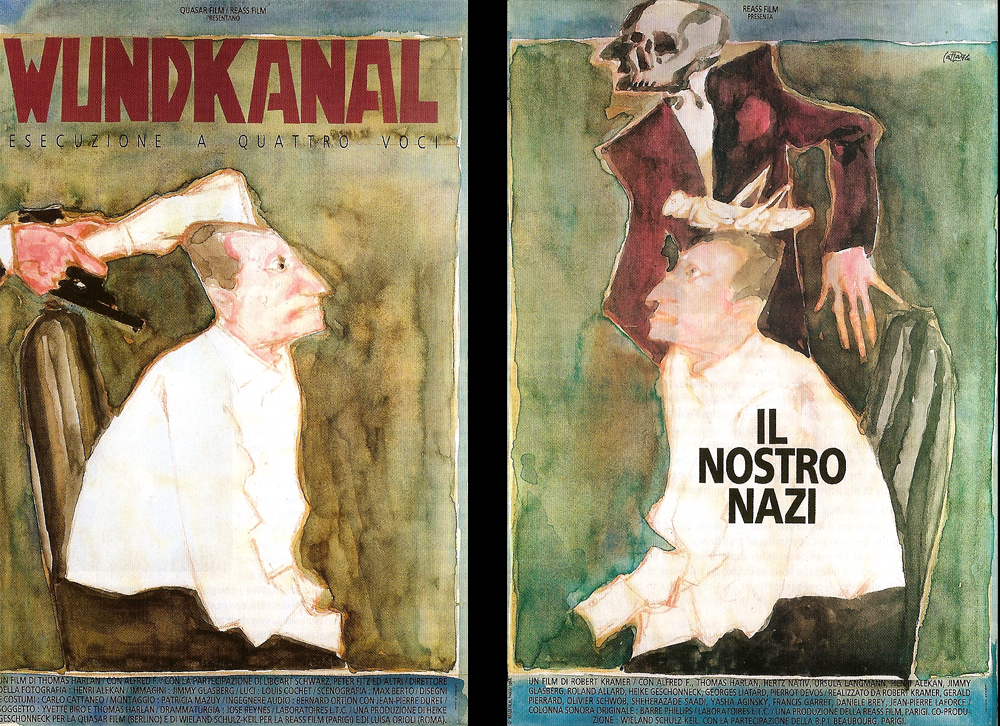

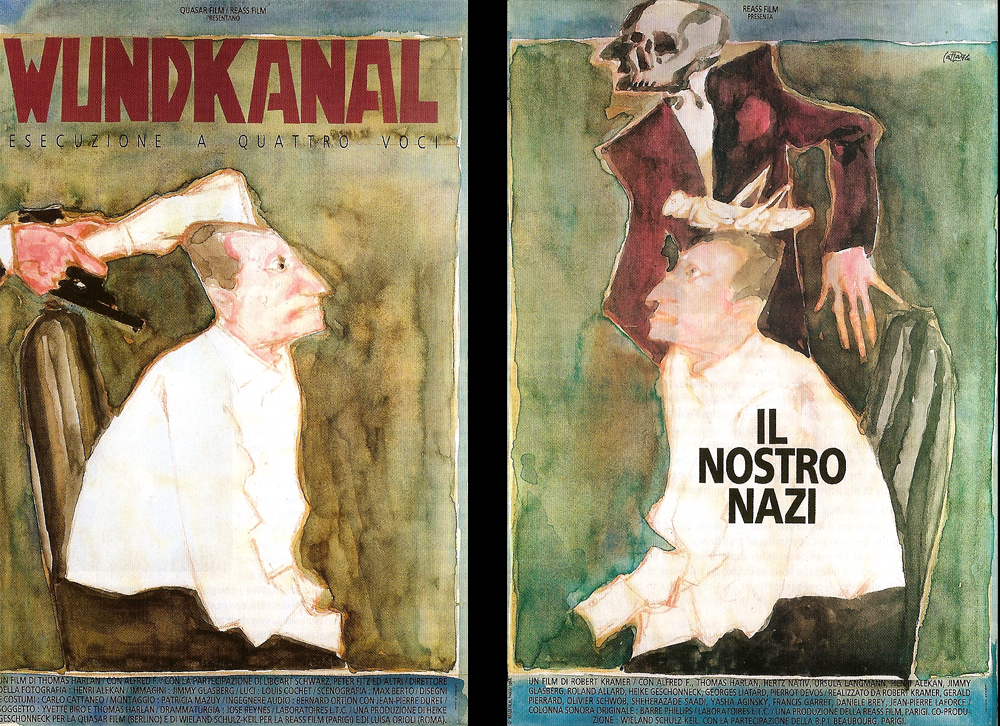

Wundkanal

1984 – RFA/France –107’

Robert Kramer

Notre Nazi

1984 – RFA/France – 116’

“My film is perhaps another fiction: the story of a certain T., son of the greatest Nazi filmmaker, and himself a film director. All his life he has tried to undo his past. Today he is shooting a fiction film, he has given the main role to a Nazi war criminal who is more or less the same age. By this act T. releases a whole torrent of unforeseeable energy which sweeps the set and even more than the set.”

– Robert Kramer

“For the first time in the history of cinema, said Louis Marcolles in le Monde (30 August 1984), two films were shot against each other; the first being fiction, the second unmasking this fiction; the first mystifying its subject (crime), the second outrageously unveiling its methods of manipulation.

Yet, both films were produced by the same producer, both in the outskirts of Paris and with two directors who are complementary to each other: Thomas Harlan, The German and Robert Kramer, the American.

Wundkanal by Thomas Harlan is a fiction film about a killer. Notre Nazi by Robert Kramer kills the fiction.

But the Killer is a real-life killer, and never before in the history of cinema did an audience get so intimate with a murderer like doctor Alfred Filbert, did an audience get so close to his face and to his skin.

Indeed, Alfred Filbert – the archetypal gentel German grandpa – belonged to the inner circle of nine men who in Hitler’s terror state planned the Holocaust; so in the film he appears as an actor and as himself, playing his own part in history.

In Wundkanal – a quiet oratorio of long sequence shots – four terrorists interrogate a war (and peace) criminal they kidknapped in Alsatia, trying to drive him to commit suicide.

In Notre Nazi the actor playing a part in a fiction film becomes a real human being again, of flesh and blood. The members of the film crew discover their sorrow and their pity as they live through unimaginable moments of violence and despair.

Two inseperable films – lashing out against each other as ruthlessly as a couple divoring publicly – “the scandal”, as Il Messagero put it, “of the 1984 Venice Film festival.” (Editions Filmmuseum)

Note: There is actually a third film in this series: Dorenavant tout sera comme d’habitude by Roland Allard, a documentary report on the making of Wundkanal and Notre Nazi. Unfortunately I haven’t been able to track down a copy.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

PROGRAMME 2

Part of the Courtisane Festival (21 – 25 March 2012)

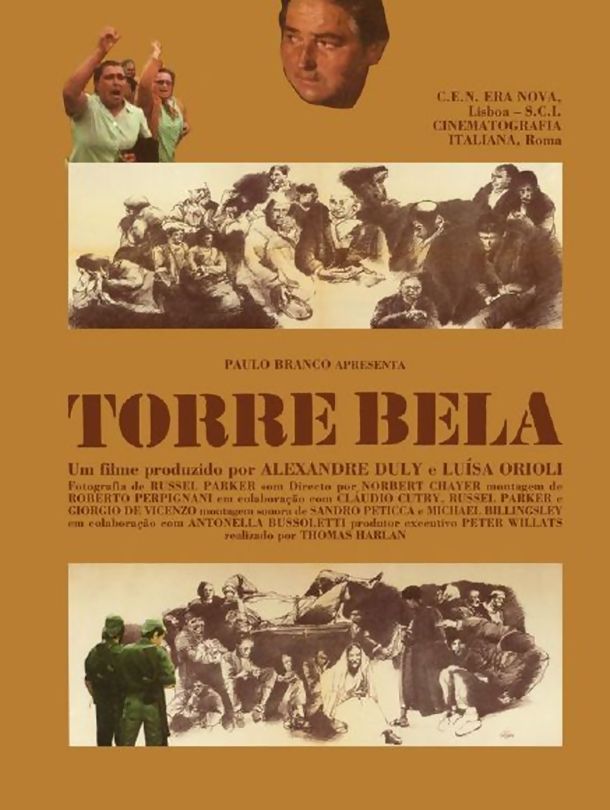

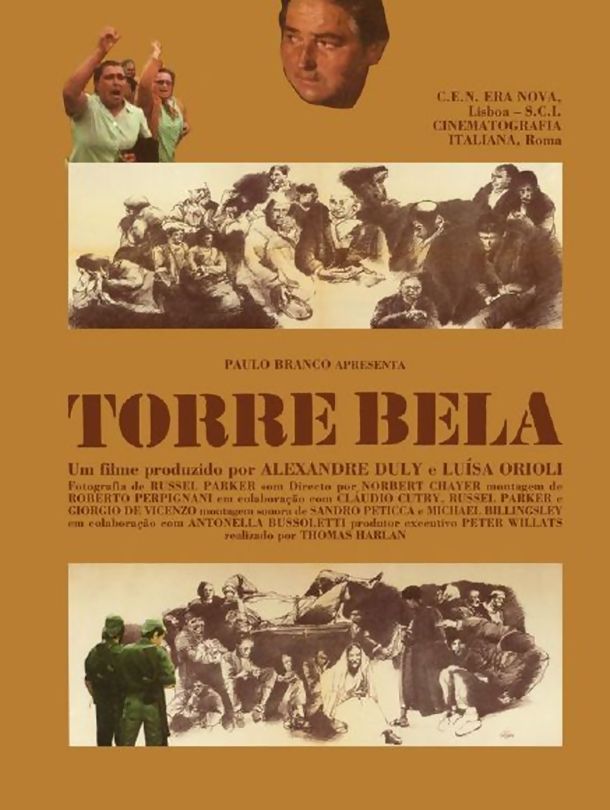

Thomas Harlan

Torre Bela

1977 – Portugal – 106’

José Filipe Costa

Linha Vermelha

2011 – Portugal – 80′

“Torre Bela is the complete opposite of what a documentary should be. The film is a film that we, in fact, did not conceive as a film, but as reality. The reality was provoked, intentionally created.”

– Thomas Harlan

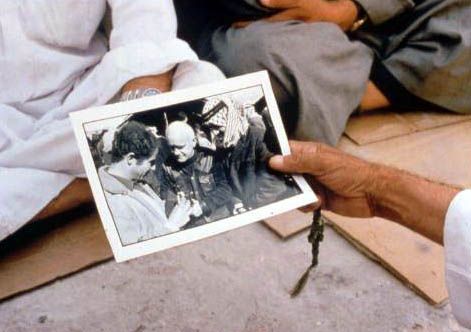

“In the revolutionary Portugal of 1975, a group of peasants occupied the vast manor and estate of Torre Bela owned by the Duke of Lafões and founded a cooperative there. The events were recorded in the film Torre Bela (1977) by the German director Thomas Harlan, son of the director Veit Harlan.

When I first started filming Red Line I asked a woman in a village near Torre Bela if she had been involved in any way in the 1975 occupation. She immediately replied that she had not and that I should ask that question to another villager who was on the other side of the street. When I asked him, the latter was extremely surprised by his neighbour’s denial: since it was even possible to see her in the film, amongst a crowd shouting slogans! After this episode I became increasingly aware of how an observational documentary had become a controversial historical object: for some it was even proof of a “crime” committed during the revolutionary period of 1975. In one of the most controversial sequences of Harlan’s film it is possible to see the squatters breaking into the palace on the estate, opening drawers and trying on the Duke’s jackets, as they play joyfully with these symbols of power. Red Line questions how the film Torre Bela played a role in how these events are viewed and examines how Thomas Harlan intervened in the flow of the events, himself becoming a squatter. Drawing on testimonies, recently discovered sound rushes and other documents, Red Line explores the complexities and ambiguities of a filmed revolution, in which the camera helps people to play new roles: “Are we actors or occupiers? If we are actors, we’re actors…” says one occupant while waiting for the camera to start filming before the group broke through the door of the palace in 1975.” (José Filipe Costa)

In the context of the research project “Figures of Dissent (Cinema of Politics, Politics of Cinema)”

KASK / School of Arts

See also ‘The militant ethnography of Thomas Harlan‘ By Serge Daney