Programme presented in the context of the Courtisane festival 2018. Curated by Stoffel Debuysere.

“I feel I have one relation with Bresson, another with Ghatak. But there is a wide difference between the two. It is strange that I have a relation with two persons so contrary in disposition. I am often trying to figure out how to strike a chord between the two. I have absorbed both of them.”

How can one mention Robert Bresson and Ritwik Ghatak in the same breath, let alone blend them into one single cinematic vision? While the films of the first are most often associated with constraint and rigor, those of the latter are generally identified with sensuousness and exuberance. While one aspired to free cinema from the influence of theatre, the other hinged his cinematic endeavors on his experience with the Indian People’s Theatre Association. Yet for all their differences and peculiarities, Bresson’s ascetic studies of penance and grace and Ghatak’s epic tales of displacement and dispossession seem to have at least one thing in common: a profound impatience with the conventions of dramatic plot structure. It is this impatience that has fuelled Mani Kaul’s ambition to pave his own path through the world of cinema, one that has guided him towards the study of other forms of art, notably of the Indian traditions of Mughal miniature painting and Dhrupad music. In these traditions, Mani Kaul (1944- 2011) found something that he wished to transpose to cinema: an abjuration of the notion of convergence that is ubiquitous in the Renaissance period in western art, in favor of a logic of dispersion and elaboration, as exemplified by the improvisation upon a single scale in Indian Raag music, able to transform a singular figure into a concert of flowing perceptions.

Perhaps this particular attention towards subtle shifts and unfolding movements can be traced back to Mani Kaul’s childhood. As a young boy growing up in the city of Udaipur in Rajasthan, Kaul was suffering from acute myopia, which for a long time he assumed as a normal mode of vision. When he finally saw the world through his first pair of glasses, he would time and again get up at the crack of dawn to see the city come alive before his eyes in a continuous play of light and colour. Right from his early documentary Forms and Design (1968), which sets up an opposition between the functional tools of the industrial age and the decorative forms from Indian tradition, Kaul made it apparent that he was interested in the possibilities of form over functionality. In his first feature film, Uski Roti (1970), inspired by a short story by Mohan Rakesh and the paintings of Amrita Sher-Gil, he pared down plot and dialogue to a bare minimum while emphasizing the experience of time and duration and blurring the distinction between the actual and the imagined. With this radical departure from the prevalent cinematic norms, Kaul established himself as one of the protagonists of the so-called “New Cinema Movement,” alongside notable colleagues such as Kumar Shahani, John Abraham and K.K. Mahajan, who had also studied with Ritwik Ghatak at the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) in Pune.

The focus on process rather than product was also central to the work of the Yukt Film Cooperative that was set up by a group of FTII graduates and students in the mid-1970s, in response to the state of emergency that Prime Minister Indira Gandhi declared across India. Kaul, by then a renowned filmmaker, collaborated on their interpretation of Ghashiram Kotwal (1977), based on a popular Marathi play of the same name, which draws out sharp parallels between that dark period of repression and the authoritarian Peshwa regime that ruled over western India on the eve of European colonization. Although the film might appear like a deviance in Kaul’s trajectory, its mixture of history and mythology, traditional folk forms and complex visual structures, also brings into focus some of the concerns that are central to his cinematic research. His study of Indian aesthetics, folk art and music would become more prevalent in subsequent documentary features such as Dhrupad (1982), focused on the legendary Dagar family of musicians, and Mati Manas (1984), about the ancient tradition of terracotta artisanry and the myths associated with it. By that time, Kaul had begun his studies of Dhrupad music with one of the members of the Dagar family, Ustad Zia Moiuddin, and derived a number of cinematic approaches from this musical idiom. As critic Shanta Gokhale has noted: “Classical Indian music is to Mani Kaul the purest artistic search … Just as a good musician has mastered the musical method of construction which saves his delineation of a raga from becoming formless, so a good filmmaker has a firm control over cinematic methods of construction and can therefore allow himself to improvise.”

Towards the end of the 1980s, Kaul found another gateway for his cinematic search in the literature of Dostoyevsky, of whom he adapted A Gentle Creature and The Idiot. Twenty years after Bresson adapted the first story into Une femme douce (1969), Kaul made his own version with Nazar (1989), whose concert of exchanged glances and delicate gestures unfolds like a musical performance sliding from one note to another. While fine-tuning the process of precise preparation combined with an embrace of the dissonant and the aleatory, Kaul ventured to let his compositions drift ever further away from linearity and unity, allowing for the expression of multiple flows. “A film should not replicate the rhythms of daily life,” he would say, “it should create its own rhythms.” Mani Kaul kept on pursuing his explorations until his untimely death in 2011, leaving behind a wealth of films and writings which unfortunately remain all too invisible to this day. This program wants to pay homage to his work by not only showing a varied selection of his films but also by tracing a lineage that extends from his mentors Robert Bresson and Ritwik Ghatak to the recent work of Gurvinder Singh, one of the numerous filmmakers who continue to gracefully prolong the singular legacy of Mani Kaul.

Full programma can be found on www.courtisane.be. In collaboration with the Essay Film Festival in Birkbeck, with the support of the National Film Development Corporation of India (NFDC), Cinemas of India and Films Division. This program would not have been possible without the help of Gurvinder Singh, Ashish Rajadhyaksha, Arindam Sen, Ricardo Matos Cabo, K. Hariharan, Gurudas Pai, Surama Ghatak, Matthew Barrington.

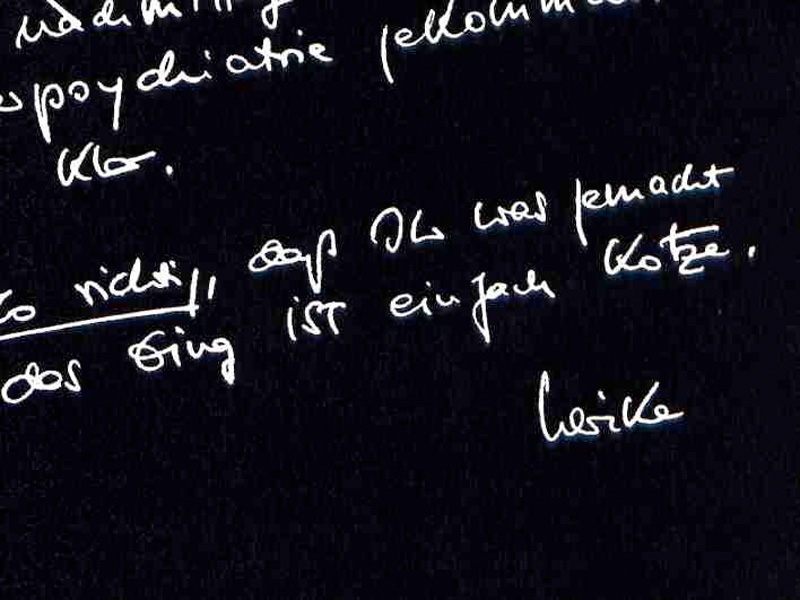

On the occasion of this program dedicated to the work of Mani Kaul, Courtisane has collected a series of writings and interviews in a small-edition publication.