Conversation between Stoffel Debuysere and C.W. Winter & Anders Edström, Courtisane festival 2021

Have you ever lived in a film? Ever had the feeling that cinema could, at least for a day, let you sway to the natural and human rhythms of a place unknown to you, get lost in its landscapes and sound fields, become familiar with its customs and traditions? If one recent film is worthy of such merit, it is undoubtedly The Works and Days (of Tayoko Shiojiri in the Shiotani Basin) (2020), the second film by C.W. Winter and Anders Edström, shot in a rural village of forty-seven inhabitants in the mountains of Kyoto Prefecture, Japan. For eight hours, divided into five chapters, the film follows the daily groove and grind of the oldest family in the village, the Shiojiri-Shikatas, whose members have been farming the land for eleven generations in constant dialogue with their natural environment, and their circle of acquaintances. The protagonist is Tayoko, the grandmother of the family, who diligently discharges her mundane duties and faces change and loss throughout the shifting seasons. Anders Edström, a renowned Swedish photographer who has maintained close ties with the family for two decades, and C.W. Winter, a California-born CalArts alumnus attached to Oxford University, have distilled an unforgettable epic from this special place and the prosaic lives of its inhabitants, which, against all appearances, has been achieved through thoughtful construction and thorough staging.

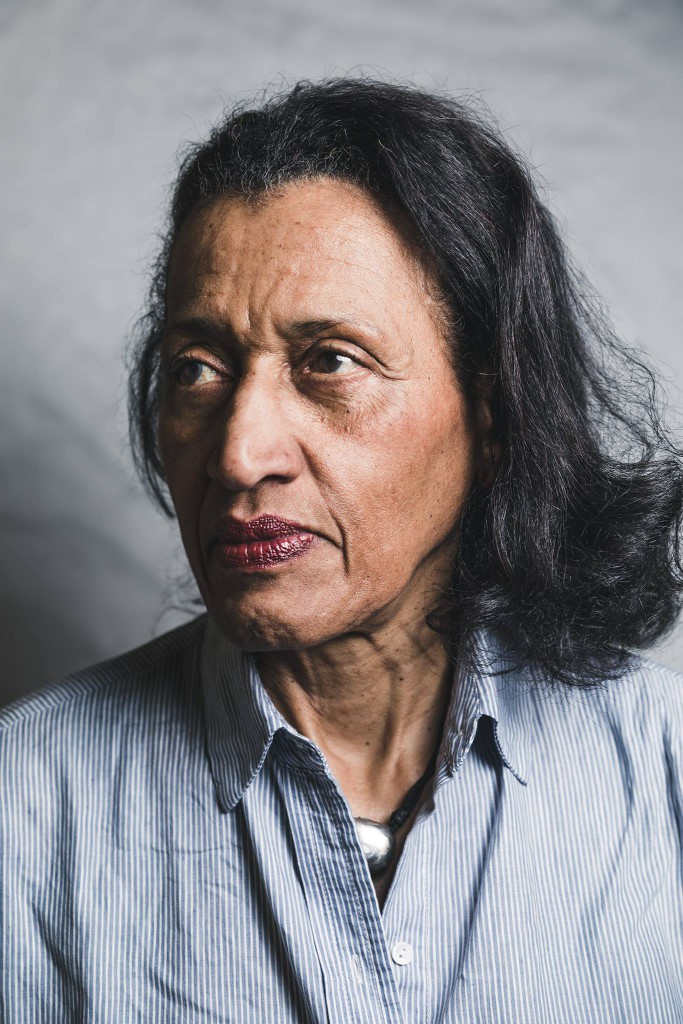

The filmmakers previously applied a similar approach, which they themselves have described as a “topological reworking of the real into the fictional,” when making The Anchorage (2009), a portrait of Ulla Edström, Anders’ mother. The film is a reconstruction of three days in her life on a Swedish archipelago around Stockholm, during which isolation, serenity and routine are broken by the appearance of a mysterious hunter. Once more, plot is secondary to the sophisticated attention paid to the everyday exchanges between the human and the natural, the lived and the constructed. But whereas The Anchorage seeks rather a formal homogeneity, The Works and Days draws on a multitude of formal and sensory registers, with the dedication to sound timbre and composition particularly notable.

This preoccupation with sound is no accident: indeed, both creators share a love of the work of sound artists such as Alvin Lucier, Éliane Radigue or Akio Suzuki, which can be heard subtly in their most recent film. One of their heroes is guitar improviser-par-excellence Derek Bailey, of whom they made a portrait sketch in 2003, driven by a shared fascination with duration and “the idea of delivering with a restraint that emerges over extended time”– a description that also graces their own work. If Bailey’s spirit permeates the work of C.W. Winter and Anders Edström, it is almost certainly to be found in their non-idiomatic approach: a cinematic approach founded on discipline and dissensus, openness to contingency and investment over time. An approach that does not advocate for the overly determined and pre-ordained, but for cinema as a medium of shared experiences and lasting rewards.