The people are missing. With these words, Gilles Deleuze, taking his cues from Paul Klee and Franz Kafka, once described the essence of what he considered to be a “modern” political cinema: the people are not there, or at least not yet. It is clear to us now, as it was for Deleuze back then, that cinema can no longer be thought of as the democratic art form par excellence, able to convert “the masses” into a genuine subject, nor is it the revolutionary medium capable of communicating the promise of a new future for all men alike. Indeed, we have drifted far away from the utopian dreams of such Soviet directors as Vertov or Eistenstein, inventors of a language meant to construct the sensible reality of communism, just as we have lost touch with the “primitive” social realism of the Lumières or Griffith, the stubborn humanism of Chaplin or Rossellini, or the heteroclite communitarianism of Ford or Mann.

Is it any wonder that their figurations of “the people” hardly work any more, in a time when forms for making socio-political conflicts visible are covered up by identity issues, when the end of the “myths” of class struggle has been loudly trumpeted, a time when yesterday’s exploited seem to have traded places with the marginalized and displaced of today, and humanity has all together shifted to the side of humanitarianism, annihilating political subjectivity by reducing it to the absolute victim, “bare life” stripped down to animality, or to its terrifying double: the inhuman perpetrator denying all humanity? How can the relationship between political truth and cinematographic appearance still be thought of today, now that the traditional borders of social divisions and the dialectic of human and citizen can apparently no longer be represented, now that people are more than ever “exposed”, yet at the same time affirmed in their impossibility to appear?

The people are not there. But have they ever been? Actually, the idea of the missing people can be traced back even further, to the days of Karl Marx, who, in The Holy Family, relentlessly dismissed Eugène Sue’s popular novel Les Mystères de Paris, as a manifestation of “petit-bourgeois morality”. In the curious, emphatic gaze of a young writer – an enthusiast of the 19th-century Parisian “physiologies” once described by Walter Benjamin as “moral dioramas” – and a philanthropist eager to mend social wounds, Marx seized the moment at a point when the dominant democratic figuration of “the people” was already established. Sue, in his own literary work, had proposed an image of society in which everyone can be immediately identified and confirmed by anyone, a society inhabited by people represented in all their familiarity, always already there.

At the end of the 1970s, Jacques Rancière defined this as a “voyeurist-unanimist” fiction, a fiction that displays the spectacle of social diversity – particularly on the fringes of society – “under the double gaze of a voyeur who feels as comfortable in high as in low places and a reformer who acknowledges social plagues and invents remedies”. It is this taxonomist logic that Rancière recognizes as characteristic of the fiction de gauche that he saw advancing in French cinema at that time: a leftist fiction in which the ambiguities of the social and the divergences in the history of the people were absorbed in this speechless “sociological majority”, which François Mitterand celebrated on the evening of his victory in 1981. Precisely in his rejection of this dominant, consensual figuration of social identification, it was Marx who made the people with unspeakable features into a name without a face. According to Rancière, “The people are what is not there yet, never in the right place, never ascribable to the place and time where anxieties and dreams await.”

“The People”. Today, even writing these words has become difficult, tainted as they are by overhanging notions of nationalism and populism. Nationalism identifies politics solely with the identity of an imagined homogeneous community (particular uses of the word Volk come to mind), while populism is used as a convenient catchphrase to discredit all possible resistance to the management of the economic and social interests of the self-defined community. The concept of “populism” – borrowed from the Leninist dictionary – perpetually presents an image of the people as an ignorant crowd, an irrational flock driven by blind rejection, targeting either those in power (allegedly stemming from a failure to understand the complexity of political mechanisms) or the “others”, those out of place (seemingly generated by an unreasonable fear of change and progress). It is a blunt return of stereotypes cultivated more than a century ago as a reaction against the rise of the workers’ movements, which were discarded as naïve and all too impressionable.

Even if “the people” as such do not exist, their images do exist, and this is one that threatens to override all others. But “the people” have always been a double figure: as Rancière and others have reminded us, the demos in ancient Athens referred to both the common people and the people as a whole, to the subject of sovereignty and a populace whose existence undermines or contradicts the attainment of sovereignty (Marx: “The proletariat does not have a homeland”). It is this constant ambiguity that captures the tension between a community and its internal divisions. According to Rancière, the people emerge as political subject only when one suspends the dominant logic of identification within the existing community, according to which everyone is assigned their proper place. This implies that the people are always different from themselves and divided within themselves. At the same time, it is bound to the homonymy of these sociological figures of the people as formless mass, miserable rabble, colourful collection of picturesque features. It is in this field of tension between the inconsistency of the people as political subject and the sociological consistency of popular embodiments that the image of the people is to be constructed.

The people do not have a body, only a mise-en-scène. In this sense, the question of the figuration of the people belongs to the aesthetics of politics, to its undertaking as a reconfiguration of given perceptual forms. After all, domination itself operates across a meaningful fabric of the visible, the sayable, the thinkable and the possible: a “distribution of the sensible”, as Rancière would have it. This question necessarily intersects with that of the politics of aesthetics. As Rancière has pointed out, the time of the great political revolutions – between the French and the Soviet Revolutions – was also that of the aesthetic revolution, dispensing with the old representative canons that defined what could be represented, and how. This was the moment when the repartition of genres, styles and characters as either noble or vile, beautiful or base, was dissolved.

These old differentiations made way for new models, two types of redistribution of equality: by displacing them within the represented people themselves or by translating their indifference into the equality of form and content. The first model constructed social narratives in which the “little people” of history – Victor Hugo’s misérables – came to occupy centre stage. The latter model showed that all subjects were worthy – “Yvetot is as good as Constantinople”, wrote Gustave Flaubert – and only the chosen form could make a difference. In any case, the representation of the people became an aesthetic problem, in line with the reorganization of the relations between narrative and descriptive, fiction and signification. As they are still used today, the problems put forward by the negotiation of the contention between the so-called Hugo and Flaubert models converge with the political problems of the negotiation between political subjectivation on the one hand and figures of social identification on the other. Still, there is no way to ascertain the “good” correlation between these two relationships: it is always a struggle. The question is how to turn the cinematic form itself into a struggle.

“Cinema is true; a story is a lie”, claimed Jean Epstein. Although cinema was born at a time when stories were highly suspect, it nonetheless inherited the basic features of narrative art: representation and identification. It is according to this logic that art assumes the properties of the featured subjects. Art is supposed to be “social” when it plunges us into the destitute margins of the global socio-economic order. It is “committed” when it deals with its terrible injustices, which one assumes in turn mobilizes our commitment. This basically goes back to Plato’s principle of mimesis, denoting the concordance between the fabric of sensory signs in which a certain art form is presented, and the fabric of perception and emotion through which it is felt and understood. But of course, as Brecht already pointed out, images of factories say nothing at all about the social relationships that manifest themselves there. There can be no straight line from looking at a spectacle to understanding the state of the world, no straight line from intellectual awareness to political action.

At the same time, cinema is also a visual art form in which recognition functions photo-mechanically, with no differentiation between worthy and unworthy, a form that is constantly jeopardized by its excess of sensible information what Godard, via Manoel de Oliveira, called “that saturation of magnificent signs bathed in the light of the absence of explanation”. So the “voyeurism” of its principle and the “unanimism” of its effects are inherent to its nature, and what we see in cinema is always evoked by immediate identification with the stereotypes of the social imaginary. Throughout the history of cinema, filmmakers have had to look for more complex representations to counter these commonplaces. Eisenstein was still able to explore the autonomous sphere of the visual in order to topple the typical heroic representations à la Hugo in the mythological, replacing traditional effects produced by identification with the story and the characters with direct identification with sensible affects. Then, with the challenge of sound synchronization and its entailing added information, one had to look for other ways to elude the limits of representation and construct new relationships between appearance and reality, the visible and the hidden, the singular and the common. From Renoir and Mizoguchi to Rocha and Pasolini, they all went out of their way to create some kind of gap between their cinematic figures and the social imaginary, in a game of displacements and differentiations in which “whatever face” could stand out from the nameless crowd: a face “in which what belongs to common nature and what is singular are absolutely indifferent” (Agamben).

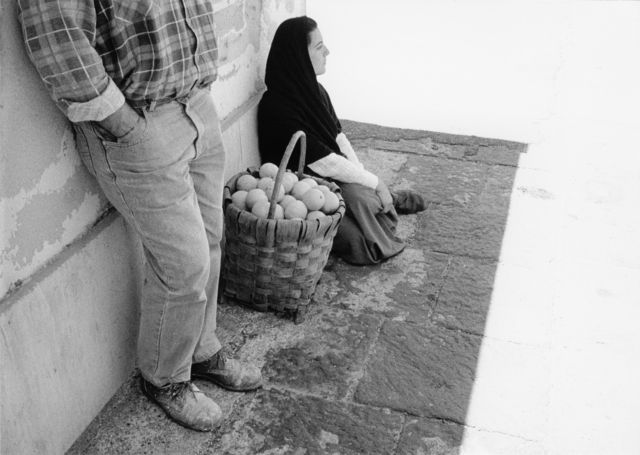

In the work of these filmmakers, and many others like them, there is a mise-en-scène of transitions between individual figures, typically characters with recognizable social traits engaged in conflict scenarios, and the visual presence of a community, represented in the frame as a collectivity that does not directly identify with a human decor of figurants or extras. Because, writes Georges Didi-Huberman, “Figurants is a word for the labyrinths that every figure conceals. (…) They are to the society of spectacle what Hugo’s misérables were to the industrial society.” In other words, they are to cinema what the people are to history: without merit or consequence. The sounds they make are nothing but clamour, the gestures they produce nothing but flutter: included in the frame but not belonging to the image.

Again, it was Eisenstein who radically overturned the hierarchical relationship between “figure” and “figurant”, between small story and grand History, although others have tried in their own ways to give those “sunk into anonymity” (Mallarmé) back their faces, their words and their capacity to divide and assemble, filming them less as indistinct mass than as dissonant community. It is in this irresolvable game of composing and decomposing the popular frame that one can find an audiovisual analogy with certain forms of relationship between social imagery and political subjectivation. This consists of transforming this space of endless, undifferentiated circulation into a space for appearance. Passolini, via Roberto Longhi, called it “figurative fulguration”; Deleuze, by way of Henri Bergson, called it “fabulation”. But in both cases, it entails a mise-en-scène that relates to a process of dis-identification, an alteration of a field of experience characterized by a certain distribution of capacities, according to which each plays its part and each part has its place. For Rancière, this crossing of identities is precisely what constitutes a fundamental condition for politics: the enactment of a capacity that was not acknowledged in the name of a subject not considered as such, or “the part of those who have no part”.

How can cinema make the people appear, as political subject, in this era defined by a professed “end of politics”? Why is it that today’s so-called “minor fiction” – and fiction in general, one might add – seems so impotent in relation to the figuration of the people? “It is not we who no longer tolerate politics. It is politics which no longer tolerates the remnants of the real of fiction,” writes Rancière. As if fiction were no longer able to deal with social reality, while reality increasingly imposes its own laws on fiction. As if cinema could do nothing more than go way beyond reality, wallowing in an accumulation of effects and intensities, or align with reality, conceding with the dominant sociological imaginary and the cultivation of a depoliticized politics – a duplicitous figure, as it happens, which is also characteristic of our consensual times, in which the real can only seem to be present in the form of the infra-political (of the everyday and the anonymous) or the ultra-political (of violence and catastrophe).

The consensual order is therefore aesthetic as well as political. The arrangement of bodies in the community is a distribution of the sensible continually oscillating between sociological proximity and fantastic distance, between recognition and exception. In any case, the visible is always anticipated by its meaning. Caught in this trap, typically resulting in sterile combinations of socio-political stereotypes and hyper-dramatic clichés, most minor or social fictions seem to have lost the capacity to get out of this “consensual circle of mutual attestation of reality and signification”. The real of fiction attests to the real, and is attested by the real in return. What is at stake here is not the “end of politics”, says Rancière, but rather the end of a certain idea of political film – a certain entanglement of the real and the fictional rendered powerless. The real is no longer something to be apprehended or attested in order to make it credible: on the contrary, it has to be invented, so that it no longer recognizes itself.

Perhaps that is why we tend to look towards other cinematic propositions for relief, other dispositions for dealing with the real and the fictive, observation and construction, action and contemplation. Perhaps that is also why we tend to recall a certain childhood of cinema, when the “story” was still subsidiary to the passion of gestures and the reflection of faces, when the mimetic qualities of cinema were still compatible with its formal powers. It is not an urge of nostalgia towards the lost paradise of mute cinema or Eisenstein’s pure language of sensations, it is rather a quest for an other sort of “mutism”, one that can oppose the deafening silence of a world without possible social figuration with the sensation of the deaf speech that mute things carry with them, in harmony with the power of speech invested in bodies. Rancière refers to the “utopia of ‘kinship’ in the image”: a true exchange between the offer and the demand of the image, between the movements of the ever-yearning camera and the craving desire of the image that raises every individual beyond mere “bare life”.

This exchange also involves another “kinship”: that between those in front of, and those behind the camera. Referring to the films of Johan van der Keuken, Serge Daney once called it “unequal exchange”, indicating not only a political reality, but also the intrinsic condition of filmmaking itself. The question of the figuration of the people cannot be separated from this question of inequality and the never-ending challenge of restoring equality. In order to respond to this challenge, it is necessary to counter the system of oppositions that are as inherent to the narrative conventions of cinema, as they are to the rhetoric of populism: between high and low, inside and outside, wealth and misery, the passivity of the “wretched of the earth” and the activities of the powerful. The process of dissociation then becomes a matter of constructing a poetic of exchange that shifts the focus from the artificial construction of identifiable identities to an aesthetic construction of proximities and distances, through which everyone is acknowledged in the ability to create one’s own character. Everything that has been seized has to be returned. Everything that has been left unspoken has to be given the chance to be taken up. It is not a matter of revealing, but simply resisting. And resistance is as much part of art as it is of politics, bound together in this irresolvable promise of a future destined to remain unaccomplished. Always, in the words of Deleuze, “in view, one hopes, of the still missing people”.

Notes taken as part of the “Figures of Dissent” research project (KASK/HoGent), in association with the screening programme Once Was Fire.