âWhat has changed?â, asked Gilles Deleuze during one of his talks on âcinema and thoughtâ in 1985, drawing on his theory of the break between two ages based on an ontology of the cinematographic image. âJust as weâve searched for the differences between the so-called ‘classical’ and ‘modern’ image, we could also search for the differences between the classical political cinema en the modern political cinema. It seems clear to me: there is an obvious change that makes that political cinema today, aside from The Straubs and Resnais, has left the West and North-America and has ended up in the Third World.â Deleuze elaborated on this fundamental change in regards to âpolitical cinemaâ in Chapter 8 of his second Cinema book (see excerpt below), in which he argued that âif there were a modern political cinema, it would be on this basis: the people no longer exist, or not yet ⦠the people are missing (â¦.) Yet this recognition is no reason for a renunciation of political cinema, but on the contrary the new basis on which it is foundedâ, not âaddressing a people which is presupposed already thereâ, but âcontributing to the invention of a peopleâ. The response to the question âwhere is the people?â, argued Deleuze, can only be undertaken by the power of âfabulationâ: âIt is the act of fabulation, letâs say âthis act too big for meâ, that constitutes a people, this is what I was trying to express in regards to Third World cinema: fabulation as a function of the poor or the damnedâ (talk of 18 June 1985).

It was only towards 1985, around the time when his two Cinema books were first published, that the issue of fabulation (sometimes translated as “story-telling”) appeared in Deleuzeâs work. Taking his cue from Bergson, he and Guattari remark in What Is Philosophy? that “Bergson analyzes fabulation as a visionary faculty very different from the imagination and that consists in creating gods and giants, âsemi- personal powers or effective presencesâ. It is exercised first of all in religions, but it is freely developed in art and literature.” Looking back, it’s clear that their interpretation of the notion of “fabulation” was preceded and prepared for by the concept of âminor literatureâ, defined in their book on Kafka (1975) as âpositively charged with the role and function of collective, and even revolutionary, enunciationâ, and furthermore ââif the writer is in the margins or completely outside his or her fragile community, this situation allows the writer all the more the possibility to express another possible community and to forge the means for another consciousness and another sensibility.â It was precisely this function that Deleuze recognized in the work of the Canadian filmmaker Pierre Perrault, who became one of the protagonists in Cinema 2: Time-image. Perrault himself preferred to describe his own work as “cinéma du vécu” (living cinema) – as oppossed to âcinéma véritéâ (truth cinema) – as a documentary cinema that seeks to seize the moment when one passes from one state to another in the act of what he called âlegendingâ. In other words: “truth” isn’t something already out there to be apprehended – it has to be created. Wary of all predetermined fiction, Perrault was interested in capturing âfiction in flagrante delictoâ and in doing so âcontribute to the invention of his (Québecois) people.â Perrault argued that neither he nor the characters in his films were capable of producing such âlegendingâ by themselves, for they need one another as “intercessors”. In a 1985 interview Deleuze described Perrault’s function as that of a âmediatorâ:

âThe formation of mediators in a community is well seen in the work of the Canadian filmmaker Pierre Perrault: having found mediators I can say what I have to say. Perrault thinks that if he speaks on his own, even in a fictional framework, he’s bound to come out with an intellectual’s discourse, he won’t get away from a âmaster’s or colonist’s discourse,â an established discourse. What we have to do is catch someone else âlegending,â âcaught in the act of legending.â Then a minority discourse, with one or many speakers, takes shape. We here come upon what Bergson calls âfabulationâ… To catch someone in the act of legending is to catch the movement of constitution of a people. A people isn’t something already there. A people, in a way, is what’s missing, as Paul Klee used to say. Was there ever a Palestinian people? Israel says no. Of course there was, but that’s not the point. The thing is, that once the Palestinians have been thrown out of their territory, then to the extent that they resist they enter the process of constituting a people. It corresponds exactly to what Perrault calls being caught in the act of legending. It’s how any people is constituted. So, to the established fictions that are always rooted in a colonist’s discourse, we oppose a minority discourse, with mediators.â

Fabulation is thus proposed as the act by which a people that doesn’t yet “exist” as such (re)invents itself. Of course filmmakers can not invent a people, they can only evoke one, through forms of “free indirect discourse” (a notion Deleuze borrowed from Passolini). As Deleuze said in one of his talks, referring to Glauber Rocha’s Terra em Transe: “Rocha has put his country in trance but thatâs all he could do. It was his own free indirect discourse but he couldnât do more â itâs a great work of art but one could still say something is missing: the people is missing.” How then can cinema contribute to political acts of fabulation? What does resistance to established fictions and opposition of a minority discourse entail? Or, in his own words: “what is the relationship between the struggles of man of the work of art?”

“This is the closest and for me the most mysterious relationship of all. Exactly what Paul Klee meant when he said: ‘you know, the people are missing’. The people are missing and at the same time, they are not missing. The people are missing means that the fundamental affinity between a work of art and a people that does not yet exist is not, will never be clear. There is no work of art that does not call on a people who does not yet exist.” (talk of 17 March 1987, also published as What is the Creative Act?)

In a 1990 interview with Antonio Negri, a few years before his death, Deleuze gave some more hints to how this relationship might be thought of:

Negri: “How can minority becoming be powerful? How can resistance become an insurÂrection? Reading you, I’m never sure how to answer such questions, even though I always find in your works an impetus that forces me to reformulate the questions theoretically and practically. And yet when I read what you’ve written about the imagination, or on common notions in Spinoza, or when I follow your description in The Time-Image of the rise of revolutionary cineÂma in third-world countries, and with you grasp the passage from image into fabulation, into political praxis, I almost feel I’ve found an answer… Or am I mistaken ? Is there then, some way for the resistance of the oppressed to become effective, and for what’s intolerable to be definitively removed? Is there some way for the mass of singularities and atoms that we all are to come forward as a constitutive power, or must we rather accept the juridical paradox that conÂstitutive power can be defined only by constituted power?”

Deleuze: “The difference between minorities and majorities isn’t their size. A minority may be bigger than a majority. What defines the majority is a model you have to conform to: the average European adult male city-dweller, for example… A minority, on the other hand, has no model, it’s a becoming, a process. One might say the majority is nobody. Everybody’s caught, one way or another, in a minority becoming that would lead them into unknown paths if they opted to follow it through. When a minority creates models for itself, it’s because it wants to become a majority, and probably has to, to survive or prosper (to have a state, be recognized, establish its rights, for example). But its power comes from what it’s managed to create, which to some extent goes into the model, but doesn’t depend on it. A people is always a creative minority, and remains one even when it acquires a majority: it can be both at once because the two things aren’t lived out on the same plane. It’s the greatest artists (rather than populist artists) who invoke a people, and find they ‘lack a people’: Mallarme, Rimbaud, Klee, Berg. The Straubs in cinema. Artists can only invoke a people, their need for one goes to the very heart of what they’re doing, it’s not their job to create one, and they can’t. Art is resistance: it resists death, slavery, infamy, shame. But a people can’t worry about art. How is a people created, through what terrible sufÂfering? When a people’s created, it’s through its own resources, but in away that links up with something in art (Garrel says there’s a mass of terrible suffering in the Louvre, too) or links up art to what it lacked. Utopia isn’t the right concept: it’s more a question of a ‘fabulation’ in which a people and art both share. We ought to take up Bergson’s notion of fabulation and give it a political meaning”.

ââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââ-

The text below was published in ‘Cinema 2, The Time-Image’ (Athlone Press, 1989), Paragraph 3 of Chapter 8, ‘Cinema, Body and Brain, Thought’. First published as ‘Cinema 2, L’Image-temps’ (Les Editions de Minuit, 1985). Translated by Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Caleta (translation slightly modified).

Resnais and the Straubs are probably the greatest political film-makers in the West, in modern cinema. But, oddly, this is not through the presence of the people. On the contrary, it is because they know how to show how the people are what is missing, what is not there. Thus Resnais, in La guerre est finie, in relation to a Spain that will not be seen: do the people in the old central committee stand with the young terrorists or the tired militant? And the German people in the Straubs’ Nicht Versohnt (‘Not reconciled’): has there ever been a German people, in a country which has bungled its revolutions, and was constituted under Bismarck and Hitler, to be separated again? This is the first big difference between classical and modern cinema. For in classical cinema, the people are there, even though they are oppressed, tricked, subject, even though blind or unconscious. Soviet cinema is an example: the people are already there in Eisenstein, who shows them performing a qualitative leap in Staroye i novoye (‘The General Line’ aka ‘Old and New’), or who, in Ivan Grozniy (‘Ivan the Terrible’), makes them the advanced edge held in check by the tsar; and, in Pudovkin, it is on each occasion the progression of a certain awareness which means that the people already has a virtual existence in process of being actualized; and in Vertov and Dovzhenko, in two different ways, there is a unanimity which calls the different peoples into the same melting-pot from which the future emerges. But unanimity is also the political character of American cinema before and during the war: this time, it is not the twists and turns of class struggle and the confrontation of ideologies, but the economic crises, the fight against moral prejudice, profiteers and demagogues, which mark the awareness of a people, at the lowest point of their misfortune as well as at the peak of their hope (the unanimism of King Vidor, Capra, or Ford, for the problem runs through the Western as much as through the social drama, both testifying to the existence of a people, in hardships as well as in ways of recovering and rediscovering itself).(1) In American and in Soviet cinema, the people are already there, real before being actual, ideal without being abstract. Hence the idea that the cinema, as art of the masses, could be the supreme revolutionary or democratic art, which makes the masses a true subject. But a great many factors were to compromise this belief: the rise of Hitler, which gave cinema as its object not the masses become subject but the masses subjected; Stalinism, which replaced the unanimism of peoples with the tyrannical unity of a party; the break-up of the American people, who could no longer believe themselves to be either the melting-pot of peoples past or the seed of a people to come (it was the neo-Western that first demonstrated this break-up). In short, if there were a modern political cinema, it would be on this basis: the people no longer exist, or not yet … the people are missing.

No doubt this truth also applied to the West, but very few authors discovered it, because it was hidden by the mechanisms of power and the systems of majority. On the other hand, it was absolutely clear in the third world, where oppressed and exploited nations remained in a state of perpetual minorities, in a collective identity crisis. Third world and minorities gave rise to authors who would be in a position, in relation to their nation and their personal situation in that nation, to say: the people are what is missing. Kafka and Klee had been the first to state this explicitly. The first said that minor literatures, “in the small nations”, ought to supplement a “national consciousness which is often inert and always in process of disintegration”, and fulfill collective tasks in the absence of a people; the second said that painting, to bring together all the parts of its “great work”, needed a “final force”, the people who were still missing.(2) This was all the more true for cinema as mass-art. Sometimes the third world film-maker finds himself before an illiterate public, swamped by American, Egyptian or Indian serials, and karate films, and he has to go through all this, it is this material that he has to work on, to extract from it the elements of a people who are still missing (Lino Brocka). Sometimes the minority film-maker finds himself in the impasse described by Kafka: the impossibility of not “writing”, the impossibility of writing in the dominant language, the impossibility of writing differently (Pierre Perrrault encounters this situation in Un pays sans bon sens, the impossibility of not speaking, the impossibility of speaking other than in English, the impossibility of speaking English, the impossibility of settling in France in order to speak French … ), and it is through this state of crisis that he has to pass, it is this that has to be resolved. This acknowledgement of a people who are missing is not a renunciation of political cinema, but on the contrary the new basis on which it is founded, in the third world and for minorities. Art, and especially cinematographic art, must take part in this task: not that of addressing a people, which is presupposed already there, but of contributing to the invention of a people. The moment the master, or the colonizer, proclaims “There have never been people here”, the missing people are a becoming, they invent themselves, in shanty towns and camps, or in ghettos, in new conditions of struggle to which a necessarily political art must contribute.

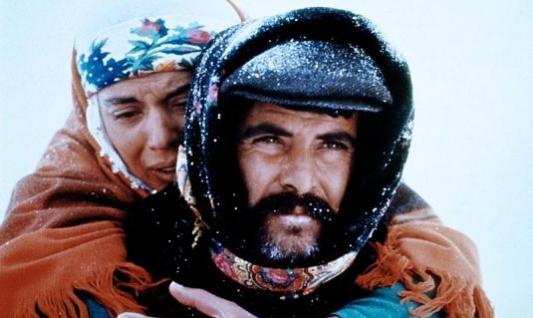

There is a second big difference between classical and modern political cinema, which concerns the relationship between the political and the private. Kafka suggested that “major” literatures always maintained a border between the political and the private, however mobile, whilst, in minor literature, the private affair was immediately political and “entailed a verdict of life or death”. And it is true that, in the large nations, the family, the couple, the individual himself go about their own business, even though this business necessarily expresses social contradictions and problems, or directly suffers their effects. The private element can thus become the place of a becoming conscious, in so far as it goes back to root causes, or reveals the “object” that it expresses. In this sense, classical cinema constantly maintained this boundary which marked the correlation of the political and the private, and which allowed, through the intermediary of an awareness, passage from one social force to another, from one political position to another: Pudovkin’s Mat (‘Mother’) discovers the son’s real object in fighting, and takes it over; in Ford’s The Grapes of Wrath, it is the mother who sees clearly up to a certain point, and who is relieved by the son when conditions change. This is no longer the case in modern political cinema, where no boundary survives to provide a minimum distance or evolution: the private affair merges with the social – or political – immediate. In Güney’s Yol, the family clans form a network of alliances, a fabric of relationships so close-knit that one character must marry the wife of his dead brother, and another go far away to look for his guilty wife, across a desert of snow, to have her punished in the proper place; and, in Süru (‘The Herd’) as in Yol, the most progressive hero is condemned to death in advance. It could be said that this is a matter of archaic pastoral families. But, in fact, what is important is that there is no longer a “general line”, that is, of evolution from the Old to the New, or of revolution which produces a leap from one to the other. There is rather, as in South American cinema, a juxtaposition or compenetration of the old and the new which “makes up an absurdity”, which assumes “the form of aberration”.(3) What replaces the correlation of the political and the private is the coexistence, to the point of absurdity, of very different social stages. It is in this way that, in Glauber Rocha’s work, the myths of the people, prophetism and banditism, are the archaic obverse of capitalist violence, as if the people were turning and increasing against themselves the violence that they suffer from somewhere else out of a need for idolization (Deus e o Diabo na Terra do Sol, ‘Black God and White Devil’). Gaining awareness is disallowed either because it takes place in the air, as with the intellectual, or because it is compressed into a hollow, as with Antonio das Mortes, capable only of grasping the juxtaposition of two violences and the continuation of one by the other.

What, then, is left? The greatest ‘agitprop’ cinema that has ever been made: the agitprop is no longer a result of a becoming conscious, but consists of putting everything into a trance, the people and its masters, and the camera itself, pushing everything into a state of aberration, in order to communicate violences as well as to make private business pass into the political, and political affairs into the private (Terra em Transe, ‘Earth Entranced’). Hence the very specific aspect assumed by the critique of myth in Rocha: it is not a matter of analysing myth in order to discover its archaic meaning or structure, but of connecting archaic myth to the state of the drives in an absolutely contemporary society, hunger, thirst, sexuality, power, death, worship. In Asia, in Brocka’s work, we can also find the immediacy of the raw drive and social violence underneath the myth, for the former is no more “natural” than the latter is “cultural”.(4) A lived actual which at the same time indicates the impossibility of living can be extracted from myth in other ways, but continues to constitute the new object of political cinema: putting into a trance, putting into a crisis. In Pierre Perrault, it is a matter of a state of crisis and not of trance. It is a matter of stubborn quests rather than of violent drives. However, the aberrant quest for French ancestors (Le regne du jour, Un pays sans bon sens, C’etait un Quebecois en Bretagne) testifies in its own way, beneath the myth of origins, to the absence of boundary between the private and the political, but also to the impossibility of living in these conditions, for the colonized person who comes up against an impasse in every direction.(5) It is as if modern political cinema were no longer constituted on the basis of a possibility of evolution and revolution, like the classical cinema, but on impossibilities, in the style of Kafka: the intolerable. Western authors cannot save themselves from this impasse, unless they settle for a cardboard people and paper revolutionaries: it is a condition which makes Comolli a true political film-maker when he takes as his object a double impossibility, that of forming a group and that of not forming a group, “the impossibility of escaping from the group and the impossibility of being satisfied with it” (L’ombre rouge).(6)

If the people are missing, if there is no longer consciousness, evolution or revolution, it is the scheme of reversal which itself becomes impossible. There will no longer be conquest of power by a proletariat, or by a united or unified people. The best third world film-makers could believe in this for a time: Rocha’s Guevarism, Chahine’s Nasserism, black American cinema’s blackpowerism. But this was the perspective from which these authors were still taking part in the classical conception, so slow, imperceptible and difficult to site clearly. The death-knell for becoming conscious was precisely the consciousness that there were no people, but always several peoples, an infinity of peoples, who remained to be united, or should not be united, in order for the problem to change. It is in this way that third world cinema is a cinema of minorities, because the people exist only in the condition of minority, which is why they are missing. It is in minorities that private business is immediately political. Acknowledging the failure of fusions or unifications which did not re-create a tyrannical unity, and did not turn back against the people, modern political cinema has been created on this fragmentation, this break-up. This is its third difference. After the 1970s, black American cinema makes a return to the ghettos, returns to this side of a consciousness, and, instead of replacing a negative image of the black with a positive one, multiplies types and ‘characters’, and each time creates or re-creates only a small part of the image which no longer corresponds to a linkage of actions, but to shattered states of emotions or drives, expressible in pure images and sounds: the specificity of black cinema is now defined by a new form, “the struggle that must bear on the medium itself” (Charles Burnett, Robert Gardner, Haile Gerima, Charles Lane).(7) In another style, this is the compositional mode of Chahine in Arab cinema: Iskanderija… lih? (‘Why Alexandria?’) reveals a plurality of intertwined lines, primed from the beginning, one of these lines being the principal one (the story of the boy), the others having to be pushed until they cut across the principal one; and Hadduta misrija (‘An Egyptian Story’ aka al-Dhakira, ‘Memory’) leaves no place for the principal line, and pursues the multiple threads which end in the author’s heart attack, conceived as internal trial and verdict, in a kind of Why Me?, but where the arteries of the inside are in immediate contact with the lines of the outside. In Chahine’s work, the question “why” takes on a properly cinematographic value, just as much as the question “how” in Godard. “Why?” is the question of the inside, the question of the I: for, if the people are missing, if they are breaking up into minorities, it is I who am first of all a people, the people of my atoms as Carmelo Bene said, the people of my arteries as Chahine said (for his part, Gerima says that, if there is a plurality of black “movements”, each film-maker is a movement in himself). “But why?” is also the question from the outside, the question of the world, the question of the people who, missing, invent themselves, who have a chance to invent themselves by asking the I the question that it asked them: Alexandria-I, I-Alexandria. Many third world films invoke memory, implicitly or even in their title, Perrault’s Pour la suite du monde, Chahine’s al-Dhakira, Khleifi’s Al Dhakira al Khasba (‘Fertile Memory’). This is not a psychological memory as faculty for summoning recollections, or even a collective memory as that of an existing people. It is, as we have seen, the strange faculty which puts into immediate contact the outside and the inside, the people’s business and private business, the people who are missing and the I who is absent, a membrane, a double becoming. Kafka spoke of this power taken on by memory in small nations: “The memory of a small nation is no shorter than that of a large one, hence it works on the existing material at a deeper level.” It gains in depth and distance what it lacks in extent. It is no longer psychological nor collective, because each person “in a little country” inherits only the portion due to him, and has no goal other than this portion, even if he neither recognizes nor maintains it. Communication of the world and the I in a fragmented world and in a fragmented I which are constantly being exchanged. It is as if the whole memory of the world is set down on each oppressed people, and the whole memory of the I comes into play in an organic crisis. The arteries of the people to which I belong, or the people of my arteries …

But is this I not the I of the third world intellectual, whose portrait Rocha and Chahine among others have often sketched, and who has to break with the condition of the colonized, but can do so only by going over to the colonizer’s side, even if only aesthetically, through artistic influences? Kafka pointed to another path, a narrow path between the two dangers: precisely because “great talents” or superior individualities are rare in minor literatures, the author is not in a condition to produce individual utterances which would be like invented stories; but also, because the people are missing, the author is in a situation of producing utterances which are already collective, which are like the seeds of the people to come, and whose political impact is immediate and inescapable. The author can be marginalized or separate from his more or less illiterate community as much as you like; this condition puts him all the more in a position to express potential forces and, in his very solitude, to be a true collective agent, a collective leaven, a catalyst. What Kafka suggests for literature is even more valid for cinema, in as much as it brings collective conditions together through itself. And this is in fact the last characteristic of a modern political cinema. The cinema author finds himself before a people which, from the point of view of culture, is doubly colonized: colonized by stories that have come from elsewhere, but also by their own myths become impersonal entities at the service of the colonizer. The author must not, then, make himself into the ethnologist of his people, nor himself invent a fiction which would be one more private story: for every personal fiction, like every impersonal myth, is on the side of the “masters”. It is in this way that we see Rocha destroying myths from the inside, and Perrault repudiating every fiction that an author could create. There remains the possibility of the author providing himself with “intercessors”, that is, of taking real and not fictional characters, but putting these very characters in the condition of “making up fiction”, of “making legends”, of “fabulation”. The author takes a step towards his characters, but the characters take a step towards the author: double becoming. Fabulation is not an impersonal myth, but neither is it a personal fiction: it is a word in act, a speech-act through which the character continually crosses the boundary which would separate his private business from politics, and which itself produces collective utterances.

Daney observed that African cinema (but this applies to the whole third world) is not, as the West would like, a cinema which dances, but a cinema which talks; a cinema of the speech-act. It is in this way that it avoids fiction and ethnology. In Ceddo, Ousmane Sembene extracts the fabulation which is the basis of living speech, which ensures its freedom and circulation, which gives it the value of collective utterance, thus contrasting it with the myths of the Islamic colonist.(8) Was this not already Rocha’s way of operating on the myths of Brazil? His internal critique would first isolate a lived present beneath the myth, which could be intolerable, the unbelievable, the impossibility of living now in “this” society (Deus e o Diabo na Terra do Sol, Terra em Transe); then he had to seize from the unliving a speech-act which could not be forced into silence, an act of fabulation which would not be a return to myth but a production of collective utterances capable of raising misery to a strange positivity, the invention of a people (O Dragão da Maldade Contra o Santo Guerreiro (‘Antonio das Mortes’), Der Leone have sept cabeças (‘The Lion Has Seven Heads’), Cabeças Cortadas (‘Severed Heads’)).(9) The trance, the putting into trances, are a transition, a passage, or a becoming; it is the trance which makes the speech-act possible, through the ideology of the colonizer, the myths of the colonized and the discourse of the intellectual. The author puts the parties in trances in order to contribute to the invention of his people who, alone, can constitute the whole [ensemble]. The parties are again not exactly real in Rocha, but reconstructed (and in Sembene they are reconstituted in a story which goes back to the seventeenth century). It is Perrault, at the other end of America, who addresses real characters, his “intercessors”, in order to prevent any fiction, but also to carry out the critique of myth. Operating by putting into crisis, Perrault will isolate the fabulation speech-act, sometimes as the generator of action (the reinvention of porpoise-fishing in Pour la suite du monde), sometimes taking itself as object (the search for ancestors in Le regne du jour), sometimes bringing about a creative simulation (the elk-hunt in La bete lumineuse), but always in such a way that fabulation is itself memory, and memory is invention of a people. Everything perhaps culminates in Le pays de la terre sans arbres, which brings all the ways together, or, by contrast, in Un pays sans bon sens, which minimizes them (for, here, the real character has the most solitude, and does not even belong to Quebec, but to a tiny French minority in an English country, and leaps from Winnipeg to Paris the better to invent his belonging to Quebec, and to produce a collective utterance for it).(10) Not the myth of a past people, but the fabulation of the people to come. The speech-act must create itself as a foreign language in a dominant language, precisely in order to express an impossibility of living under domination. It is the real character who leaves his private condition, at the same time as the author his abstract condition, to form, between the two, between several, the utterances of Quebec, about Quebec, about America, about Britanny and Paris (free indirect discourse). In Jean Rouch, in Africa, the trance of the maîtres fous is extended in a double becoming, through which the real characters become another by fabulation, but the author, too, himself becomes another, by providing himself with real characters. It may be objected that Jean Rouch can only with difficulty be considered a third world author, but no one has done so much to put the West to flight, to flee himself, to break with a cinema of ethnology and say Moi un Noir, at a time when blacks play roles in American series or those of hip Parisians. The speech-act has several heads, and, little by little, plants the elements of a people to come as the free indirect discourse of Africa about itself, about America or about Paris. As a general rule, third world cinema has this aim: through trance or crisis, to constitute an assemblage which brings real parties together, in order to make them produce collective utterances as the prefiguration of the people who are missing (and, as Klee says, “we can do no more”).

ââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââââ-

Notes

(1) For example on democracy, the community and the necessity of a “leader” in King Vidor’s work, cf. Positif, no. 163, novembre 1974 (articles by Michel Ciment and Michael Henry).

(2) cf. Kafka, Journal, 25 December 1911 (and letter to Brod, June 1921); Klee, On Modern Art, trans. Paul Findlay, London: Faber, 1966, p. 55. (“We have found parts, but not the whole. We still lack the ultimate power, for: the people are not with us. But we seek a people. We began over there in the Bauhaus. We began there with a community to which each of us gave what he had. More we cannot do.”) Carmelo Bene has also said: “I make popular theatre. Ethnic. But it is the people who are missing” (Dramaturgie, p. 113).

(3) Roberto Schwarz and his definition of ‘tropicalism’, Les Temps modernes, no. 288, juillet 1970.

(4) On Lino Brocka, his use of myth and his cinema of drives, cf. Cinématographe, no. 77, avril 1982 (especially the article by Jacques Fieschi, ‘Violences’).

(5) On the critique of myth in Perrault, cf. Guy Gauthier, ‘Une ecriture du reel’, and Suzanne Trudel, ‘La quete du royaume, trois hommes, trois paroles, un langage’, in Ecritures de Pierre Perrault, Edilig. Suzanne Trudel distinguishes three kinds of impasse, genealogical, ethnic and political (p. 63).

(6) Jean-Louis Comolli, interview, Cahiers du cinéma, no. 333, mars 1982.

(7) Yann Lardeau, ‘Cinema des racines, histoires du ghetto’, in Cahiers du cinéma, no. 340, octobre 1982.

(8) cf. Serge Daney, La rampe, Cahiers du cinéma / Gallimard, pp. 118- 23 (especially the character of the story-teller).

(9) On Rocha’s critique of myth and the evolution of his work, cf. Barthelemy Amengual, Le cinema novo brésilien, Etudes cinématographiques, II (p. 57: “the counter-myth, as one says counter-fire”).

(10) Ecritures de Pierre Perrault: on real characters, and the speech-act as fabulation function, “flagrant offence of making legend”, cf. the interview with René Allio (on La bête lumineuse, Perrault would say: “I recently came across an unsuspected country … Everything in this apparently quiet country is made into legend as soon as one dares to talk about it.”).

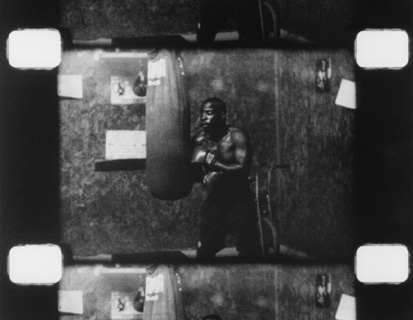

Meditations on Revolution (1997- 2003) is the title of a series of films that represent the heart of Fenz’s oeuvre. “Revolution” does not refer here to the overthrow of a form of state, but to the countless nameless revolutions inscribed in rural and urban spaces, steeped in hollowed and smiling faces, dancing on the rhythms of a world in constant transition. “Revolution” takes here the form of a sensible world. A dance lesson in the bustling streets of Havana, children playing in a shanty town in Rio de Janeiro, the hard-trained torso of a boxer in Greenville, Mississippi, the proud but fatigued monologue of a jazz musician (the late Marion Brown) in New York: the politics of Fenz’s films does not lie in lecturing on economical or geo-political issues, but in the reframing of bodies, the world they live in and the place that they take in that world. Politics resides in the confrontation of power and impotence, reality and possibility, inside and outside, “here” and “there”. It lies in the way films are made. “Say how things are real”, as Godard proclaims, is what making political films implies. Making films politically: “to say how things really are”.

Meditations on Revolution (1997- 2003) is the title of a series of films that represent the heart of Fenz’s oeuvre. “Revolution” does not refer here to the overthrow of a form of state, but to the countless nameless revolutions inscribed in rural and urban spaces, steeped in hollowed and smiling faces, dancing on the rhythms of a world in constant transition. “Revolution” takes here the form of a sensible world. A dance lesson in the bustling streets of Havana, children playing in a shanty town in Rio de Janeiro, the hard-trained torso of a boxer in Greenville, Mississippi, the proud but fatigued monologue of a jazz musician (the late Marion Brown) in New York: the politics of Fenz’s films does not lie in lecturing on economical or geo-political issues, but in the reframing of bodies, the world they live in and the place that they take in that world. Politics resides in the confrontation of power and impotence, reality and possibility, inside and outside, “here” and “there”. It lies in the way films are made. “Say how things are real”, as Godard proclaims, is what making political films implies. Making films politically: “to say how things really are”.