ARTIST IN FOCUS: Philippe Grandrieux

In the context of the Courtisane Festival 2012 (Gent, March 21 – 25).

Additional screenings at INSAS on March 26.

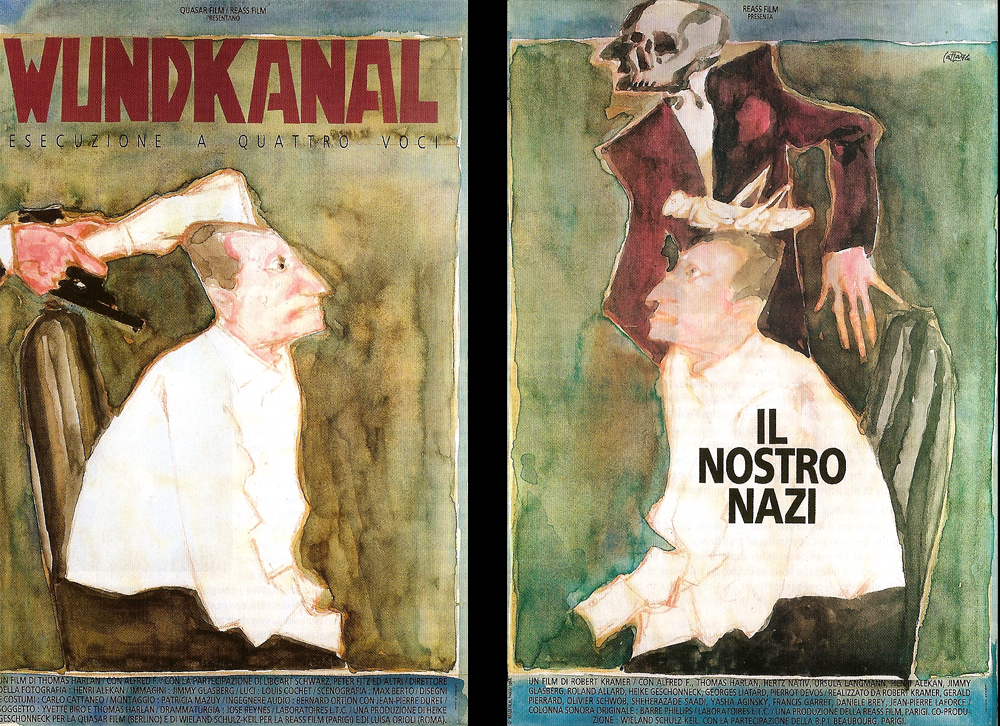

Cinema as a sensual experience: this understanding is the basis of the extraordinary work of Philippe Grandrieux (FR, 1954). The French filmmaker, who studied at INSAS in Brussels, has made quite an impression during the past decade with feature films such as Sombre (1998) and La Vie Nouvelle (2002), but his idiosyncratic oeuvre also includes documentaries and video art works, many of which have never been shown in Belgium before. His cinematic vision is clearly inspired by the modernist ideas of artists such as Antonin Artaud and Jean Epstein, who saw in cinema the potential to grasp the essential power and brutal beauty of reality. As very few have, Grandrieux succeeds in inscribing the most archaic and primitive sensations in the materiality of the medium. This is a cinema that vibrates and shimmers: cinematic space is transformed into a plastic mass of light, sound, colour and movement, in which form and content, figure and ground, body and matter, the abstract and the figurative fuse. At the occasion of the festival, an extensive selection of his work will be shown in Ghent and Brussels, including the first part of the film series “Il se peut que la beaute ait renforce notre resolution”, which celebrates filmmakers who in the course of the last century dedicated their work and life to resistance and emancipation.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

SAT 24.03 15:30, SPHINX

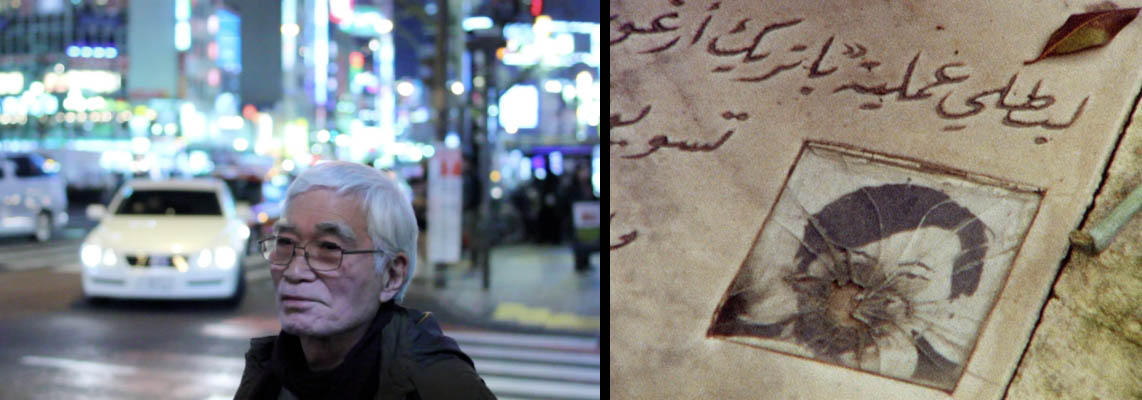

Il se peut que la beauté ait renforcé notre résolution – Masao Adachi

FR, 2011, video, colour, stereo, Japanese and French spoken, English subtitles, 75’

“A to and fro between politics and cinema, between Trotskym and Surrealism, between armed struggle and screenplays, between Palestine, Lebanon and Japan, between the day-before-yesterday and today, between beauty and resolve, between the art of eating and that of being a father, such is the risky and precise life of Masao Adachi, the monsieur with the white hair glimpsed in his delusions. And this is just how Philippe Grandrieux, faithful to his way of doing things, decided to suggest his portrait, with no a priori, without interrupting speech, filming him and listening to his words without at first understanding them, framing him in a tight close-up that is sometimes underexposed, other times overexposed, to better abandon him later for: cherry trees in blossom, the streets of Tokyo swarming with cars and passersby, familiar objects and lactescent celling light. And from time to time, Grandrieux lets speak a few shots from his earlier films, from where suddenly crops up the phrase, Genet-like, given in the title: a paradoxical program that hesitates to connect one shore to the other”. (Jean-Pierre Rehm)

SAT 24.03, 22:30 SPHINX

Sombre

FR, 1998, 35mm, colour, French spoken, English subtitles, 117’

“There is something profoundly new about Grandrieux’s plastic exploration of violence, but also something very contemporary. His approach is not based on such editing and framing effects one finds and admires in Hitchcock and Ray, nor in an exploration of excess as in Tarantino. He works on the inside of an image, on the special relation between the luminous content and the vibrant and fragmentary figuration. Grandrieux may ‘tell’ the story of a serial killer in Sombre, but the violence is both removed from the story and heightened: it descends with its hero into the dark, in scenes of a carved-up female body, captured with a hand-held 35mm camera. As Raymond Bellour observes in his eulogy and lively defence of the film, ‘Pour Sombre’: [the camera places us] among the bodies, into situations of unmitigated suffering, in order to confront us, despite the brutality of the acts, with ambiguous content, in a constantly disrupted fusion”. (Christa Blümlinger)

SUN 25.03, 13:30 SPHINX

Un lac

FR, 2009, 35mm, colour, French spoken, English subtitles, 85’

“Instead of the heavy 35mm camera painfully held on the shoulder for Sombre, it’s with a small DV camera (and all that it involves) that Grandrieux has shot Un Lac, with a freedom of mastered improvisation which is felt throughout the entire film (…). And thus the camera’s most directly sensitive recording capacity accompanies a will of great abstraction in the way that Grandrieux treats each of the components of the film, in the editing and the sound design, which is entirely constructed, as well as in the decision of lowering the level of light sensitivity, carefully respected from the shooting to the digital colourgrading and the blowup to 35mm. All of this seems to suggest that we are in front of a new way of negotiating the relation between the ‘two biggest trends in cinema, the design-tendency and the recording-tendency’. Serge Daney added ‘two ways of engaging the inhuman in the human’, explaining that it would be ‘in the middle, the ‘scene-tendency’ (…) that the inhuman is kept at a distance’.” (Raymond Bellour)

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

MON 26.03, 18:00 INSAS, Brussels

Retour à Sarajevo

FR, 1996, video, colour, Bosnian spoken, French subtitles, 70’

“Initially, this film was commissioned by Arte. The idea was to return to Sarajevo with Sada, a Bosnian woman who had spent the war in exile in Paris. As the work progressed, I realized that it was not that simple. That war had escaped me a bit, I was interested in how it could be done from Paris. It was a week after the Dayton Accords and the situation was definitely not stabilized, Sarajevo was still surrounded by the Serbs. At the same time, I’m not predisposed to be a war reporter, it’s not my story, this kind of fear does not excite me. We took one of the first busses that went back to Sarajevo and the trip was incredible. We crossed completely devastated landscapes: 300 kms of ruins between Split to and Sarajevo; a trip of countless hours through a piece of history that was absolutely shattered. We were arrested and controlled all the time, without any idea by whom. I’d never been physically in a war landscape. The film was an incredibly strong experience because it faced me with a certain responsibility, a commitment. If I had not been affronted with all these questions, with my own story and my relationship to history, perhaps I would have never embarked on a feature film. In that respect, this film seemed decisive. “(PG)

La vie nouvelle

FR, 2002, 35mm, colour, English and French spoken, French subtitles, 102’

“There was an extremely simple, basic narrative premise: a young man meets a young woman and wants her for himself, in an Orphic way. Little by little the film was constructed in terms of intensity – relations of intensity between characters who could inhabit or haunt the film. There’s the impression that everything is moving all the time, like a kind of vibrant, disturbed materiology. That’s what we were looking for: a disquieting film, very disquieting, very fragile and vibrant. Not a film like a tree, with a trunk and branches, but like a field of sunflowers, a field of grass growing everywhere. Here’s the biggest rupture: in the way the film was conceived. It was conceived and developed on questions of intensity rather than psychological relations. My dream is to

create a completely ‘Spinoza-ist’ film, built upon ethical categories: rage, joy, pride … and essentially each of these categories would be a pure block of sensations, passing from one to the other with enormous suddenness. So the film would be a constant vibration of emotions and affects, and all that would reunite us, reinscribe us into the material in which we’re formed: the perceptual material of our first years, our first moments, our childhood. Before speech. That’s the impulse – the desire – which led to the film.” (PG)

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

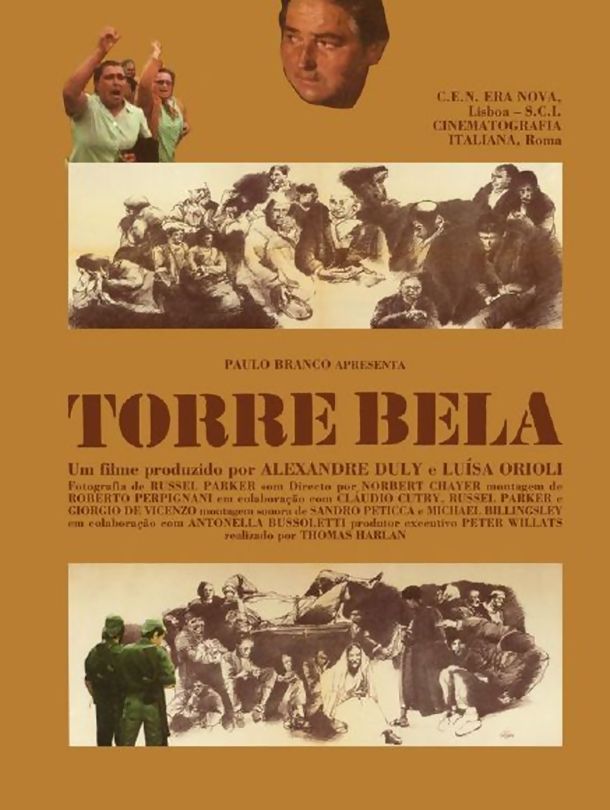

Carte Blanche to Philippe Grandrieux

SAT 24.03, 17:30 SPHINX

Edmond Bernhard

Dimanche

BE, 1962, 35mm, b&w, 20’

Too often forgotten and ignored, this is the master piece of Belgian filmmaker Edmond Bernhard, one of Grandrieux’s teachers during his studies at INSAS.

“Dimanche was supposed to be a didactic film, intended to evoke the problem of leisure. Bernhard diverts the order and outwits the trap of the ‘thematic’ film. Without resorting to any form of commentary, making use of extraordinary images sublimating common spaces (the boredom of Sundays, the changing of the guard, children playing, a runner in the woods, a football match, …), he constructs with a nifty montage an exceptional work dealing with the sense of void and the fossilisation of the world.” (Boris Lehman)

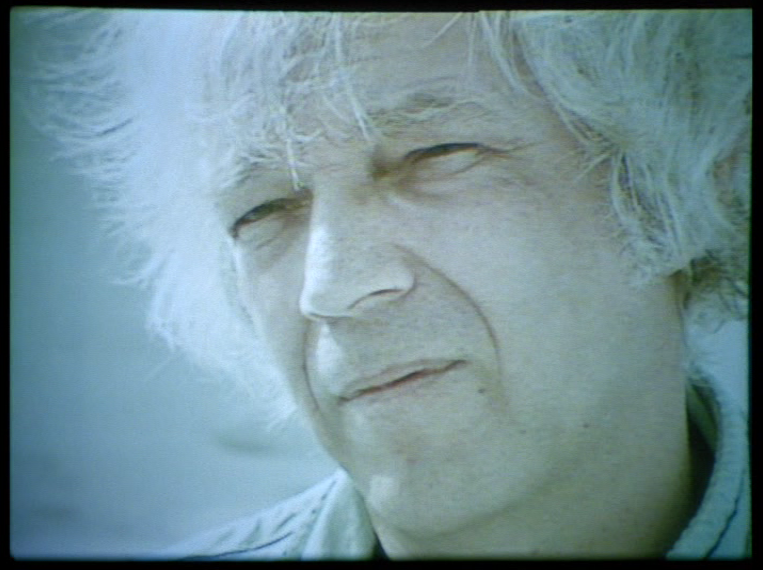

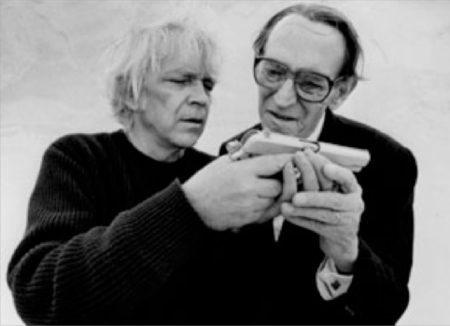

Stephen Dwoskin

The Sun and the Moon

UK , 2007, video, colour, 60’

One of the most personal and intimate films by Stephen Dwoskin. A radical portrait of lust, pain and melancholia, at the same time lurid fairytale and autobiographical essay. “The Sun and the Moon, a film fairy tale, is about two women’s terrifying encounter with ‘Otherness’ in the form of a man, abject and monstrous, and for them to either to witness, accept or partake in his annihilation. All are caught in their own isolation and are fearful of the menace that has to be met. The film, as a personal interpretation of Beauty and the Beast, enciphers concerns, beliefs and desires in seductive images that are themselves a form of camouflage, making it possible to utter harsh truths.” (SD)

Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Deutschland im Herbst (episode)

DE, 1977/78, 35mm, colour and b&w, 26’

Fassbinder’s contribution to the omnibusfilm Deutschland im Herbst, which attempted to portray the political climate in Germany in 1977 after the kidnapping and assassination of Hanns-Martin Schleyer by the Red Army Faction, and the subsequent “suicides” in Stammheim prison of three members of the Baader-Meinhof group. Exposing himself with frankness and brutality, Fassbinder conveys, in the words of Wilhelm Roth, “the feeling of powerlessness experienced by a left wing intellectual. It is not the political discussions that give this half hour its importance, but the brutality and honesty with which Fassbinder deals with himself as a man and a director.”

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Masterclass

MON 26.03 13:00 Sint-Lukas Brussel

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Avec le soutien de l’Ambassade de France en Belgique