Palestine: cartography, memory, imagery. Some notes.

(this text accompanies the exhibition ‘Drawn from Life’, hosted online by Animate Projects. The exhibition contains works by Till Roekens, Sarah Wood and Dominique Dubosc )

Cartography

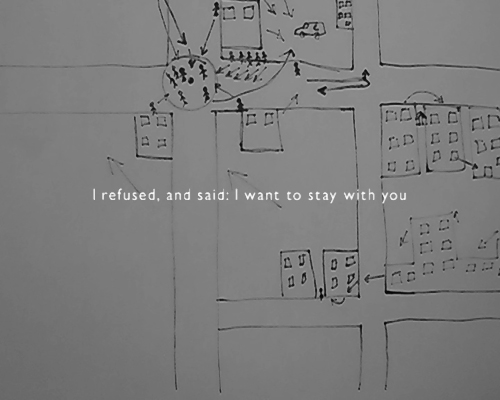

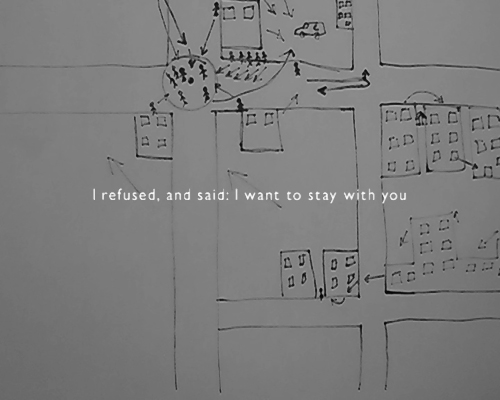

Maps are all but common in Palestine. On those that are available, hastily distributed by the Israeli PR services, there is a never a reference to the West Bank, but to Samaria and Judea, the old biblical names of the province, as if it was nothing there other than the Israeli settlements which continue to multiply like mushrooms. There is no sign either of the ‘Green Line’, the internationally recognised demarcation line between Israeli and Palestinian settlements: in these maps, the Holy Land appears as one continuous territory from the Mediterranean Sea to the River Jordan. Only those who read the small letters will notice the designations ‘Area A’ and ‘Area B’, the territories on the West Bank of the Jordan under Palestinian or shared Israel-Palestinian rule. ‘Area C’, however, which stands for the settlements under Israeli rule, the security buffer zones, the strategic areas, the settler roads and military bases, as defined during the Oslo agreements in 1993, does not appear in these maps; Israeli rule appears as self-evident. There is absolutely no indication of the countless borders, walls, fences and checkpoints that traverse the territory: those are only for the Palestinians[1].

In Oslo, Arafat suffered from this lack of reliable, well documented maps of the Palestinian Territories. The Palestinian negotiators found themselves powerless against the fruits of the systematic mapping put in place by Israel in the 1970s as a sign of their neocolonialist policy[2]. Since then, it has become evident that the agreement that should have accelerated the resolution of the conflict, played in favour of the occupier, who delayed and undermined the arrangements that were made. The ensuing ghettoisation of Palestine is the result not only of the aggressive use by Israel of its power apparatus, but also of what architect Eyal Weizman refers to as an ’architecture of occupation’: the geo-spatial and logistic mechanisms of control and division that keeps on fragmentising and isolating the Palestinian territory. Everyday needs and utilities such as housing, paving, public lightning, water supply and electricity are used as tactical tools in a long-running process during which the living environment is continuously and abruptly reconfigured, suffocating its inhabitants slowly but surely.

The doomed ‘road map’ proposed by George W Bush and his administration in 2002 as a possible solution to the conflict is nothing more than a smoke screen hiding the reality on the ground[3]. Annexation, destruction, reorganisation and subversion of space are still the order of the day in Palestine. The urban and rural environment cannot be considered simply as the backdrop of the conflict, but as an instrument of divergent political, economical and social powers. What unfolds horizontally as an arrangement of powerful manoeuvres and gradual counter movements, increasingly reveals itself on a vertical axis. The more reckless are the actions of the Israeli air force, the more underground becomes the resistance. The response to the absolute oppression of the Palestinian air space is a creative form of subterranean opposition: a rare symmetry in an predominantly asymmetrical conflict. Ultimate visibility (mapping and surveillance) versus relative invisibility (tunnels and bunkers); high-tech (satellite and GPS) versus ingeniousness (compass and drawings). Or how, for each form of cartography – traditionally associated with mechanisms of the exercise of colonial power – there exists a possibility of counter-cartography.

Memory

What memory? Whose memory? Who can still remember the tragic events of 1948? What history makes mention of the humiliation, banishment and annihilation of thousands of Palestinians during the Al-Nakba (‘the Catastrophe’)? An unspeakable trauma for some; an ugly stain for others. For some, a gruesome manifestation of a colonial ideology that still today continues to spread insidiously; for the others, an unfortunate collateral damage of an independence war between two military forces. For everyone, willingly or not, an indication of the fact that ‘Palestine’ today represents only a fifth of its original territory and a third of the Palestinian population. It’s a painful recollection that the political arena and the mainstream media tend to avoid or simply ignore for it throws a divergent light on the status and the perspectives of the Palestinians in refugee camps, on the West Bank, on the Gaza strip. Italian journalist Paolo Barnard speaks in this context of a ‘missing narrative’: just as if the French Revolution were to be described in history books as a violent outburst without historical roots or background.

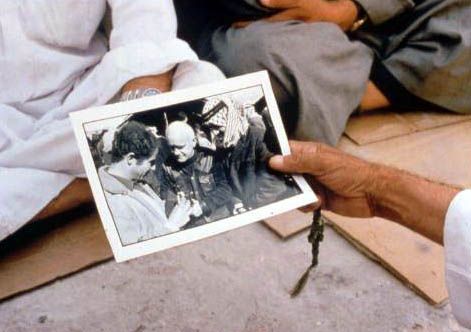

‘Nations are narrations’, according to Edward Said. Imperialism is not only about the appropriation of land, but also about the making – and the control – of the stories about whom the land belongs to, and who can cultivate it. There is no room for alternative versions. In Israel, the dominate narrative is not only inscribed in the official discourse and curriculum[4], but also in the landscape: in national parks, Palestinian olive, almond and fig trees have given way to imported conifers, erasing all evidence of Palestinian life prior to 1948. Where Palestinian villages used to be, one now finds settlements surrounded by ecologically correct spaces for leisure and entertainment[5] . How can Palestinians reclaim their memories, knowing that the common experience of the pre-Nakba period has been fragmentised? Knowing that the Palestinian geography – with the help of archaeologists and biblical experts – has been increasingly Hebraicized and that a number of archives (including the Palestinian Film Archive[6]) have disappeared or been devastated? How does a memory that chiefly consists of gaps and silences disclose itself?

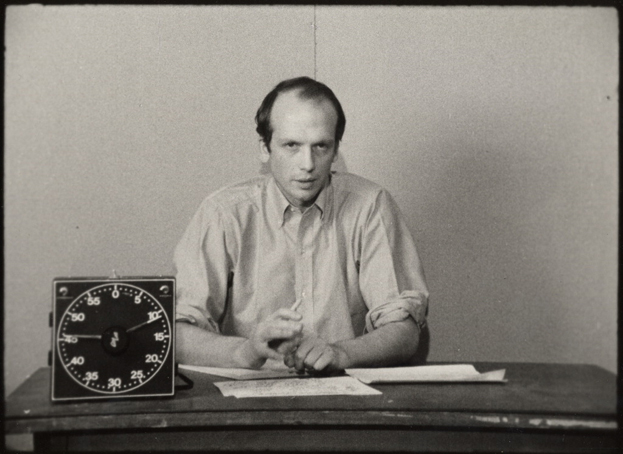

‘The point, then, isn’t to preserve memory, but to create it.’ French philosopher Jacques Rancière refers in this sentence to The Last Bolshevik[7], Chris Marker’s tribute to Soviet filmmaker Alexander Medvekin, but it can also be applied to the Palestinian situation. ‘Memory must be created against the overabundance of information as well as against its absence. It has to be constructed as the liaison between the account of the events and traces of actions, much like that ‘arrangement of incidents’, that Aristotle talks about in the Poetics and that he calls muthos: not, as it were, a ‘myth’ that points us back to some sort of collective unconscious, but a fable or fiction. Memory is the work [oeuvre] of fiction’. It is the ‘fiction’ – originally ‘fingere’ doesn’t mean ‘to feign’ but ‘to forge’ – of the ‘village memorial books’, in which are collected cartographic maps, lists, poems and drawings by Palestinian refugees. It is the ‘fiction’ of the poetry and graffiti that since the first Intifada has tinged the Palestinian side of the West Bank. It is the ‘fiction’ in the work of countless poets, filmmakers and theater writers exploring and inventing new relations between past and present, bearing witness to what is forgotten, denied, ignored. For every dominant narrative, fetishised and instrumentalised in the name of History, there are possible fictions of memory.

Imagery

What are the images of Palestine that we believe to know? A huge concrete wall, separating the weak from the mighty, the dispossessed from the prosperous. An extensive matrix of checkpoints, earth mounds, trenches, gates and roadblocks, restricting the movements of almost four million people. A country cut of its environment, its ecosystem and its chances of survival. Refugees who have been living in ‘provisional’ camps for over half a century. Families who are unable to leave their homes, while armed forces are stationed on their roof. Dried up lands that are no more viable today than the South African Bantustans were yesterday. Bulldozers demolishing homes, uprooting orchards and destroying crops. Kids throwing rubber bullets back at the same Israeli soldiers that previously fired them. 1.4 million people, mostly children, piled up in Gaza, one of the most densely populated regions of the world, with no place to run and no space to hide. ‘The world’s largest prison’, cut off from all essential supplies, bombarded by a barrage of lethal missiles for the sake of ‘war against terror’. Sabra and Chatilla. Muhammad and Jahal al-Durrah. Death and suffering.

What image is missing? ‘There is no complex image of Palestinian Reality’, wrote Serge Daney, ‘and that, I’m afraid, plays into everyone’s hands… Between the word and the thing, the word – the word ‘Palestinians’ – has won out. It’s a word with success, it’s a pure signifier, at once umbrella and alibi for everybody. And we know how much easier is to die for a word than to work for the image of a thing.’ Just as the homeland has become a slogan, so have the images we believe to know become cliché, in the sense that a cliché is an image that can no longer evolve. ‘No doubt this cliché is useful for the survival of the word ‘cause’’, wrote Daney, but it doesn’t function as much more than an advertising label. [8]‘ This is what Jean-Luc Godard also struggled with while making Jusqu’a la victoire, a documentary about the Palestinian refugee camps, which would eventually become Ici et Ailleurs: how to make an image that has not been overwhelmed by rhetorical framing[9]? In the context of one of his more recent works, Notre Musique[10], Godard points out that the Palestinians’ image is that of the ‘others’ of the Israelis: on the one hand, the intractable, anti-Semitic terrorist refugee, and on the other, the figures of helplessness and victimhood. ‘Do you know why Palestinians are famous?’, asks Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish in the film. ‘Because Israel is our enemy’.

Under every image, there is another image. Just as under Jewish settlements, Palestinian villages are buried. Just as behind the pastoral, displaced landscape paintings on the Israeli side of the wall, there is an ‘other’. It is a matter of not only seeing what there is (‘just an image’, as Godard said) but also of imagining what is missing, what has been removed from sight. ‘Absence was in their hands just as it was under their feet’, wrote Jean Genet recounting the time he spent among Feyadeen[11]. Absence is still at the heart of the Palestinians: absent from their own country[12], absent from their own image. ‘Out of place, out of time’[13]. Mahmoud Darwish once described the image that Palestinians have created for themselves as a foothold for vision: ‘When we see our faces and our blood on the screen, we applaud the image, forgetting it’s of our own making. And by the time production goes into postproduction, we are only too ready to believe it is the Other who is pointing at us. [14]‘How to visualise an absent image which is not predicated upon the insistent presence of absence? How to set up ways of seeing which are not predicated upon the predominant idea of the abstract Other? In the absence of an image, we are left to rely on its frail ghost: imagination.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

[1]Pieter van Bogaert, ‘Reality Check’. In: Pieter van Bogaert, Els Opsomer & Herman Asselberghs, Time Suspended, Square, 2004.

[2]One of Ariel Sharon’s obvious talents is the use of maps and cartography.

[3]While Israel formally accepted the Road Map, it attached fourteen reservations that completely eviscerate it.

[4]See Eyal Sivan’s Izkor: Slaves of Memory, 1991.

[5]See Illan Pappe’s The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine, Oneworld, 2006.

[6]‘Established in 1976, this was an archive of political cinema, documenting the Palestinian people’s struggle and resistance movements, as well as images of their everyday lives – homegrown film of a country and people more usually represented by western news footage. The aim of the film-makers who had established it – and in the 1970s, film-makers really did work collectively – was to make ‘a people’s cinema’. For a nation unused to film, with no infrastructure to show it, and where everyday survival seemed more vital than watching images of that survival, it was an ambitious project. But after six years, the archive was lost in the 1982 siege of Beirut’ (Sarah Wood).

[7]Chris Marker, Le Tombeau d’Alexandre, 1993.

[8]Serge Daney, ‘Before and After the Image’. Originally published in French in Revue des Etudes Palestiniennes 70, 40, Paris, Summer 1991 and in English in Documenta X.

[9]Jean-Luc Godard & Anne-Marie Mieville, Ici et Ailleurs, 1976.

[10]Jean-Luc Godard,Notre Musique, 2004.

[11]Jean Genet, Prisoner of Love, Wesleyan, 1992.

[12]Remember the early mobilising phrase of Zionism: ‘We are a people without a land, going to a land without a people.’

[13]‘Hors du Lieu, hors du temps’ (Elias Sanbar).

[14]Mahmoud Darwish, Memory for Forgetfulness: August, Beirut, 1982, University of California Press, 1995.