Lately I have been chewing a bit on an idea for a film/video program on the “cinematic night”. One catalyst has been a paper – or at least its abstract – by Eduardo Abrantes, titled ‘Night-Coloured-Eye: Night Vision in Video or the Mediated Perception of Invisibility’. He writes: “Joseph Anderson and Donald Richie, in their 1959 reference work The Japanese Film: Art and Industry, describe the distinct chromatic experience of cinematic night in western and eastern tradition. Whereas in the early colour conventions of western films night was expressed in a blue tint, in eastern films, namely Japanese and Taiwanese, the night scenes were coloured orange. Why such a radical difference in twilight tonal perception? It is interesting to notice that blue-purple and orange are complementary colours, meaning that while it is mimetically clear that a night sky might appear bluish-purple to human eyes, if one were to suddenly look towards an empty white film screen, the brain would reproduce an orange colour, owing to the physiological trait that an afterimage is produced by the fatigue of specific colour receptors. Somehow, the visible in time seems to manifest its invisible counterpart, its complement. But what happens to the colour of night in the digital age? How does video relay the chromatic experience of darkness unbound? The limited range of colour and light sensitivity that video still possesses, when compared to film, causes its technological role to become active more than passive.”

I don’t think the paper has been published yet, but I sure like to read it. This abstract already plugs into several interesting ideas: on the nuances in tonal perception in western and eastern cinema, the rise of new image technologies – night glasses, active infrared, thermal vision etc. – as commonplace tools to venture into the previously invisible, or the aesthectical differences of the cinematic night in film and video, analog and digital. Consider for example Michal Mann’s ‘Collateral’ (2004), one of the first digitally captured mainstream films to make a certain look out of digital video rather than trying to make the footage appear as it was shot in 35 millimetre film. This approach can be seen very clearly in the film as most of the scenes take place at night. Mann: “Film doesn’t record what our eyes can see at night. That’s why I moved into shooting digital video in high definition–to see into the night, to see everything the naked eye can see and more.”

This theme also relates to the “Day for night” or “nuit américaine” technique, used to simulate a night scene with special blue filters and under-exposed film. Many of the night scenes in early B-movies, Westerns, and film noir were done this way, but also in Spielberg’s ‘Jaws’ (1975), for instance. It seems like day-for-night shooting has become more common in recent years. In ‘Fresnadillo’s ’28 Weeks Later’ (2007) most of the night scenes in London were shot using a new technique created specifically for the film by director of photography Enrique Chediak. Imdb: “the scenes were shot day-for-night for three reasons. Firstly, because the filmmakers weren’t allowed to use Mackintosh Muggleton at night time. Secondly, because there is supposed to be a total shut down of all power in London, hence every building must appear light-less. However, if one were to actually shoot at night time in London, this would be impossible to capture photo-realistically and would hence involve complex post-production work removing all of the lights. By shooting during the day time however, there are few lights on in most buildings anyway, and as such, when the day-for-night treatment is applied to the film stock, everything in the image darkens equally, thus giving the impression that all of the buildings are in total darkness. Thirdly, director Juan Carlos Fresnadillo has always been a big fan of the ‘ghostly’ quality day-for-night shooting has, and he felt it would create the perfect sense of unease for the film.”

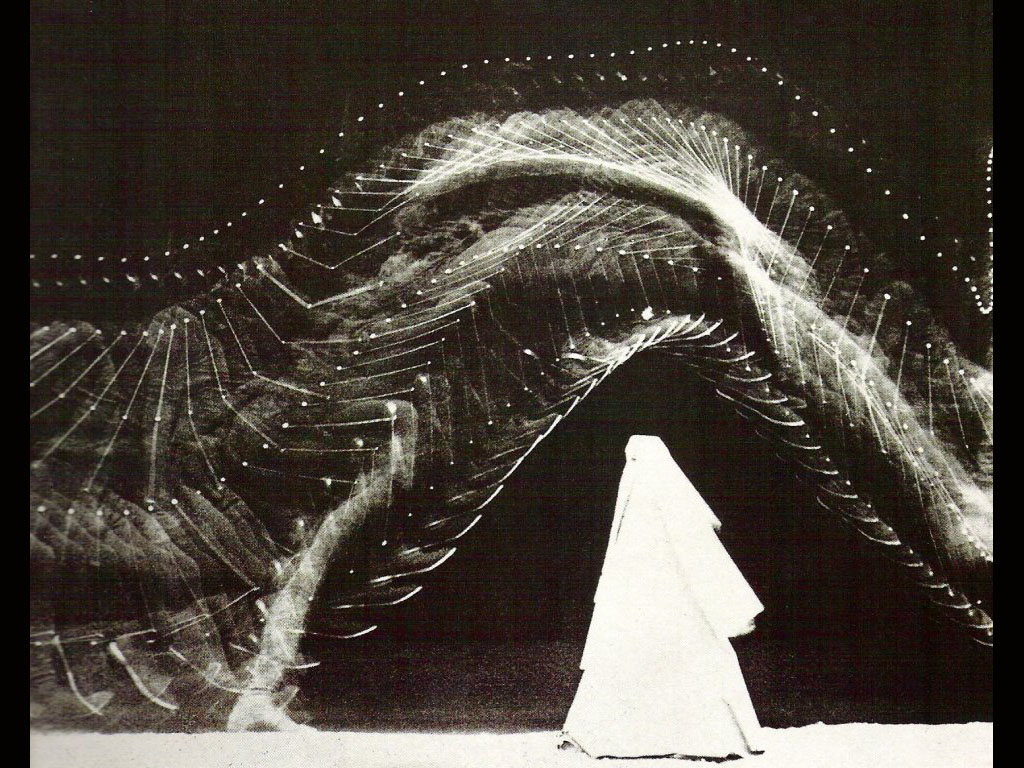

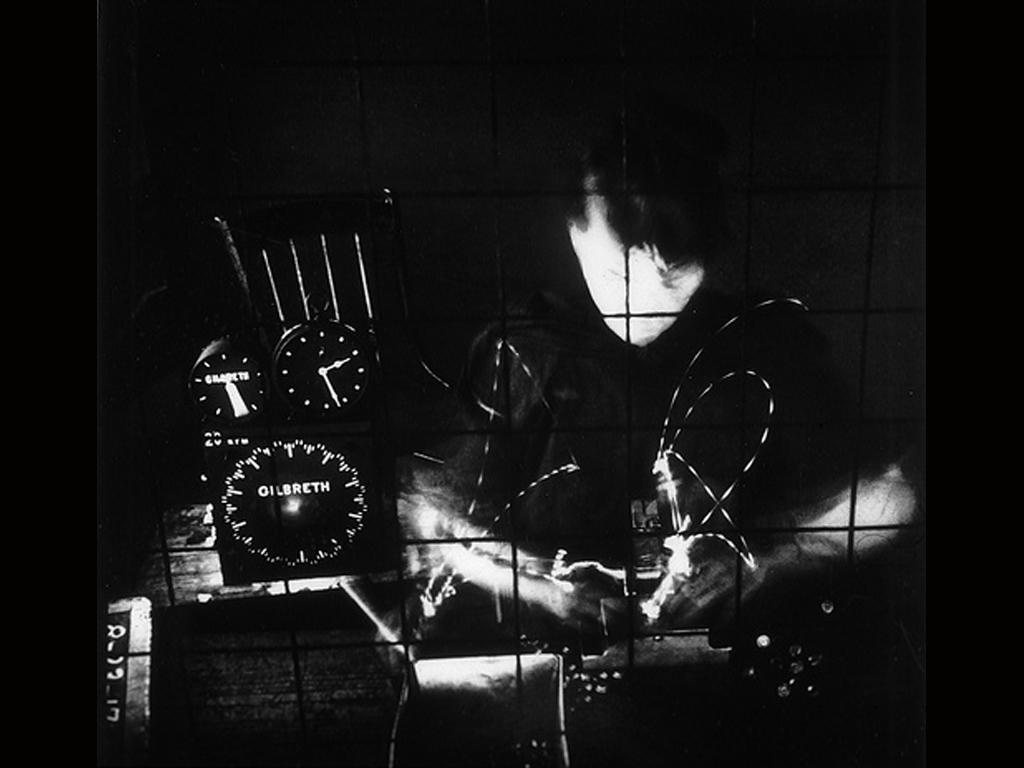

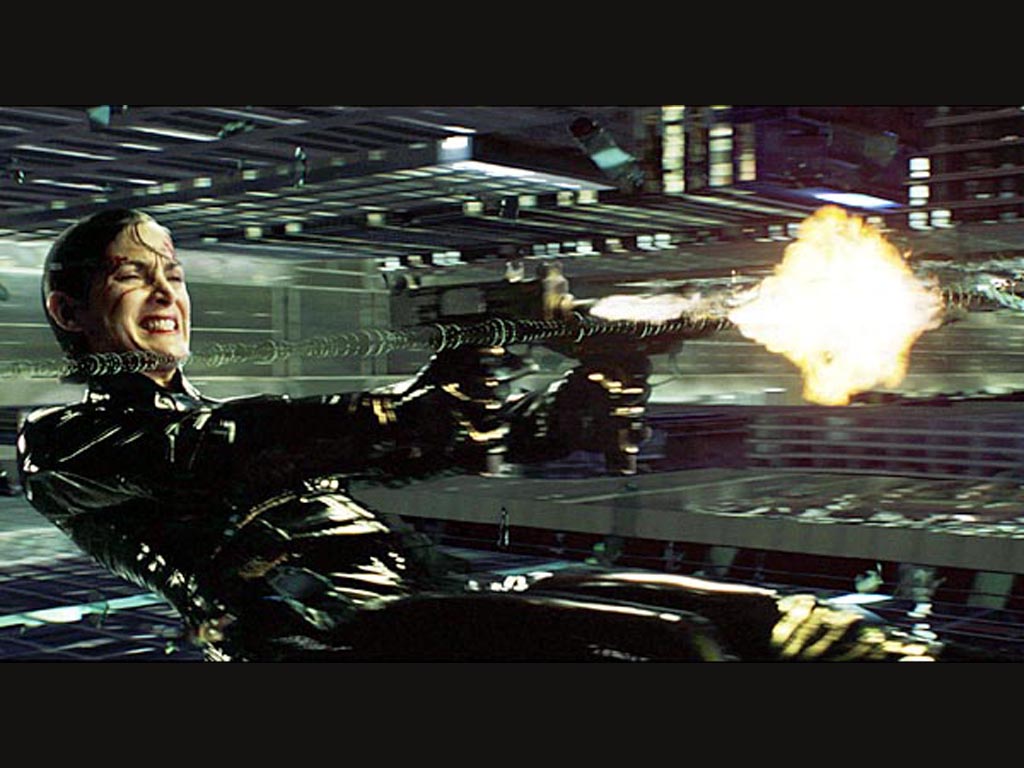

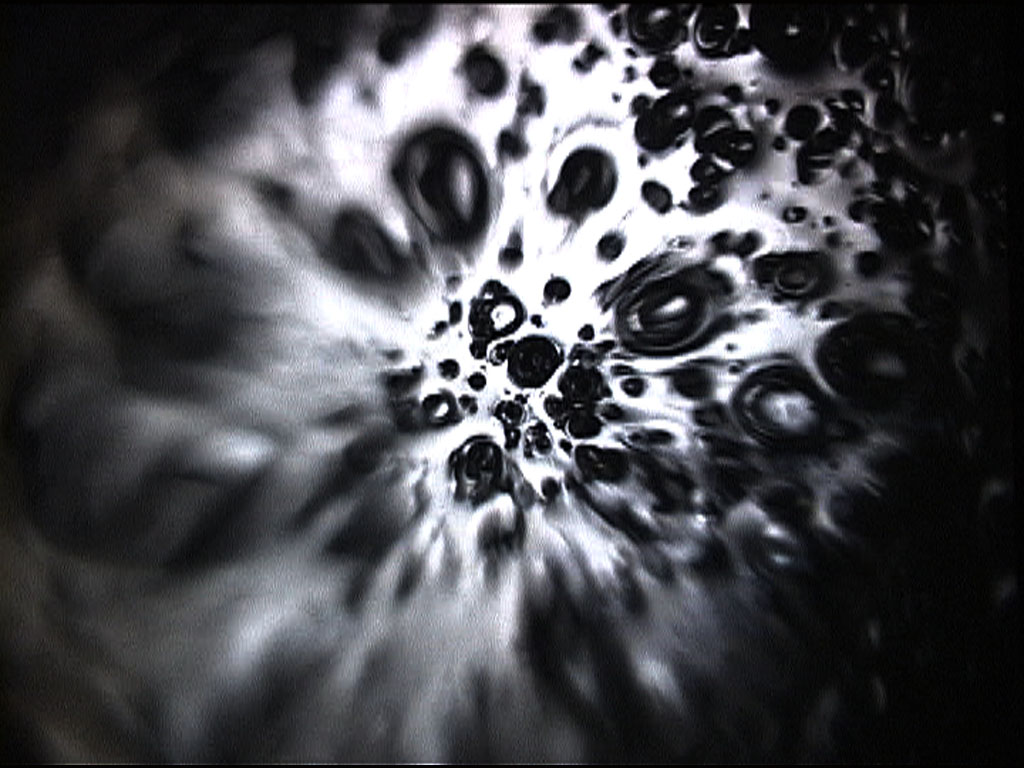

A second catalyst for exploring this theme was seeing or rather experiencing Philippe Grandrieux’ ‘La Vie Nouvelle’ (2002). At the end of this fascinating film there’s a fantastic scene filmed with a thermic camera, which is normally used by the military and engineers in order to gauge the resistance of materials. It records the different levels of temperature in a body. You can set the camera to record particular temperatures of your choice: for example if you set it between ten and eighteen degrees, variations in temperature will be indicated by variations in shades of grey. Thermic shots are in colour, but Grandrieux changed the colors in post-production. In an interview with Nicole Brenez he explains: “The principle is that it is no longer light which makes an impression. With infrared photography, you must use an infrared light, a beaming light that illuminates the bodies, and the reflection of that registers on the celluloid. But here, there is no light. It is the animal warmth of the bodies which imprints itself on the celluloid. The scene was shot in total darkness; no one could see anything except me through the camera. All the participants were in an absolute blackout, and they moved around in a deranged state. (…) There were eighty people. I had built a labyrinth inside the Fine Arts Gallery basement at Sofia. I told everyone simply to enter it. The noise they made was deafening; some of them were very scared. (…) Eric and I had worked on a project called A Natural History of Evil which began like that, a scene in which the viewer too would understand virtually nothing. They would see bodies caught up in some kind of ritual to which we would have no access, whose codes are unknown. A very archaic ritual, perhaps with glimpses of body parts, something which would be happening and repeating weirdly. I wanted total night – to work in the deepest recesses of night. (…) For example, after I’d started shooting this scene of people in darkness, I altered the thermic light level. But the image still didn’t seem strong enough, so I slowed down the speed and shot at eight images per second. And this was when I felt it started to vibrate.” The effect is mesmerizing: these are intense haptic images that propose a new way of touching. The cinematic body is no longer represented as a silhouet or flesh, but, as Fabien Gaffez suggests, “un magma d’affects, dont la

subjectivité ne se constituerait qu’à brûler sans cesse”.

There are also quite a few examples of the use of nightshot in contemporary art and videography, such as Spike Jonze’s music video for Björk’s song ‘It’s in Your Hands’ (2002).

…or this video by Anthony Goicolea, titled ‘Nail Biter’ (2002), a portrait of a young boy’s neurosis shot with an infrared night vision camera and framed in a vertical format,

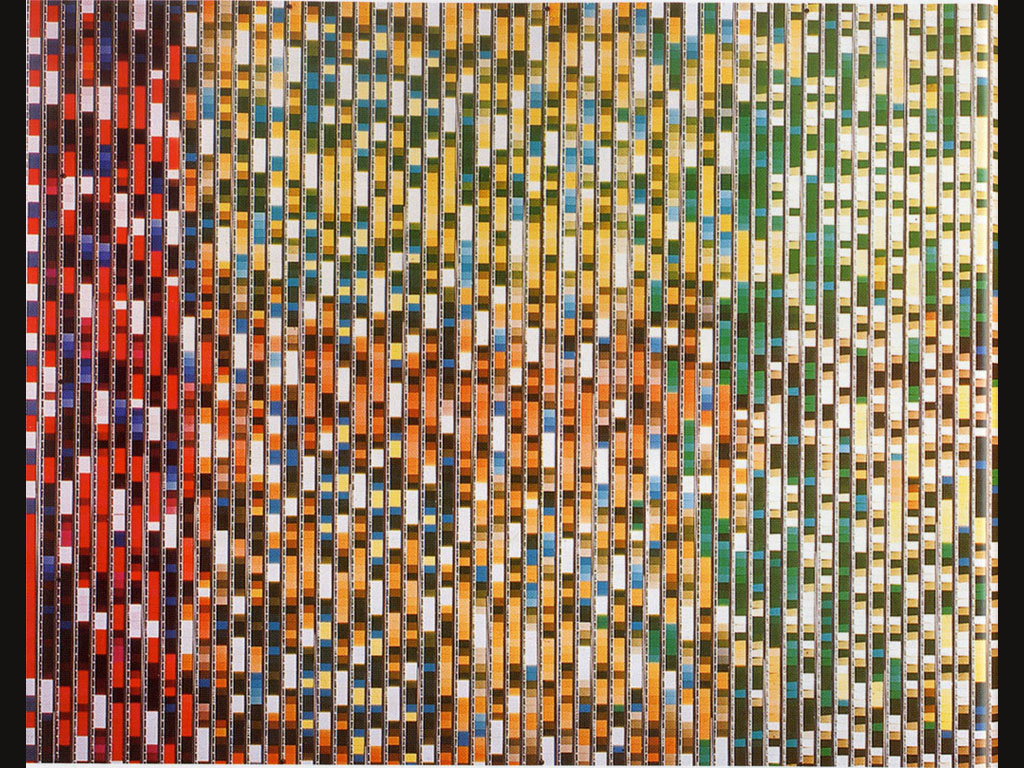

I’m also thinking about some wonderful examples of film and video works that explore nocturnal skies, like Jeanne Liotta‘s ‘Observando el Cielo’ (2007), “seven years of celestial field recordings gathered from the chaos of the cosmos and inscribed onto 16mm film from various locations upon this turning tripod Earth”. Here’s an excerpt:

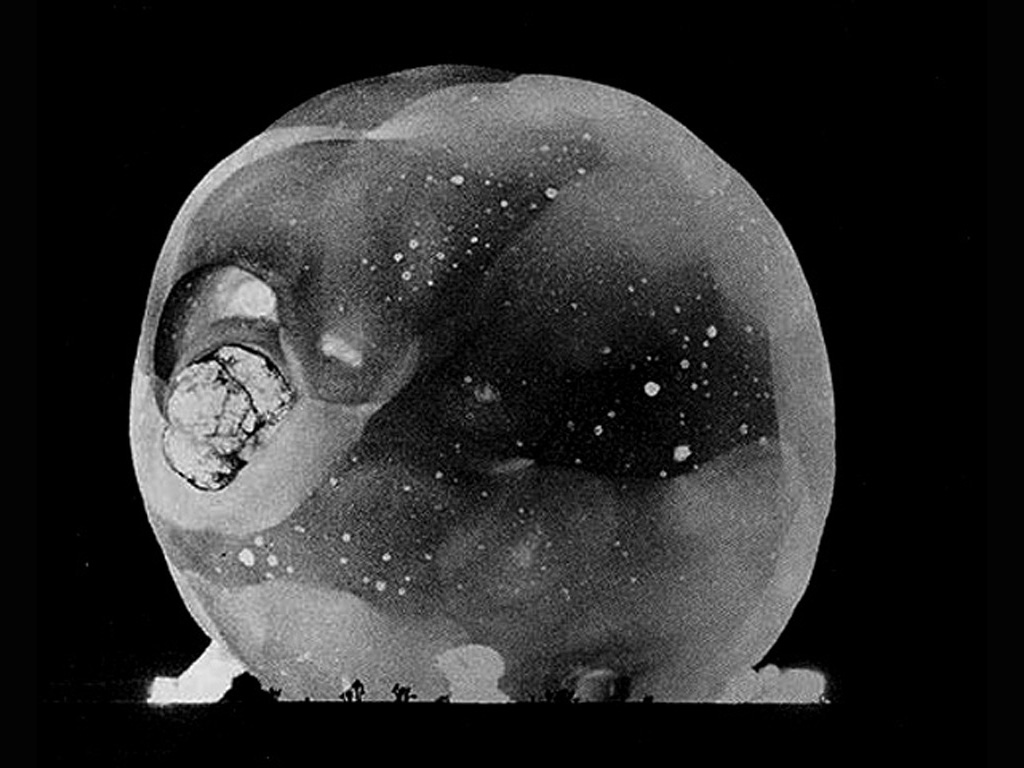

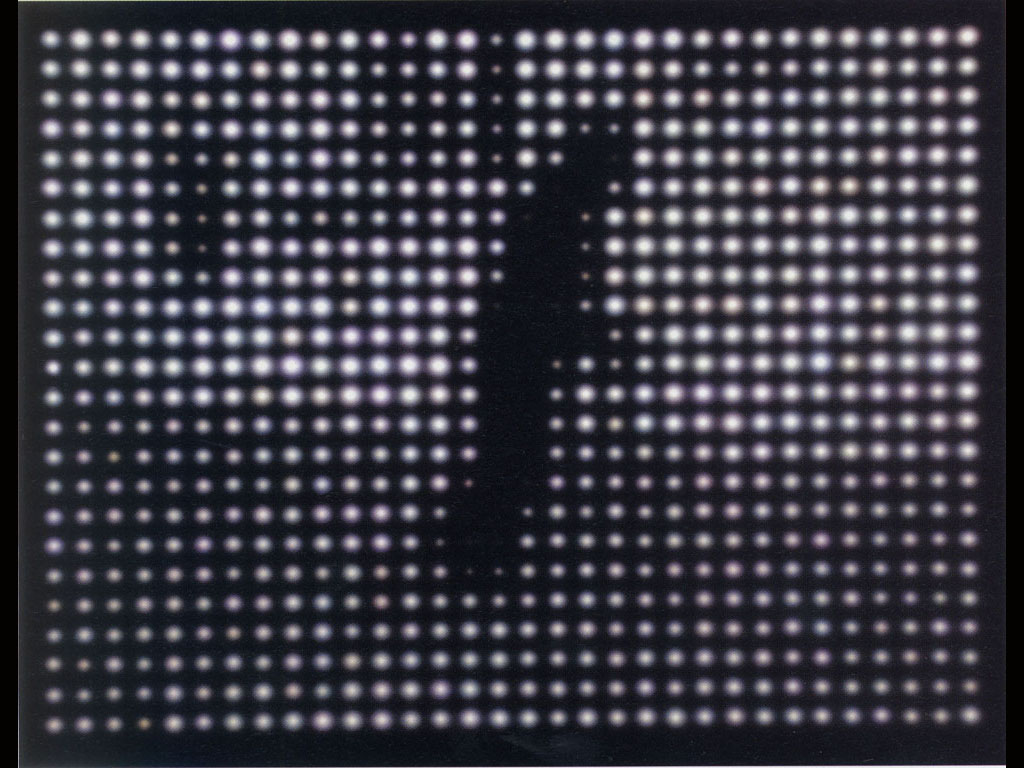

… or Hollis Frampton’s ‘Noctiluca’ (1974, part of the MAGELLAN cycle). The title (nox/luceo) means something that shines by night, i.e., the moon, and the film indeed consists of a bright sphere, sometimes white, sometimes tinted, sometimes single, sometimes doubled and overlapped.

Anyways, food for thought…