Jacques Rancière, interviewed by Diane Arnaud and Stéphane Bou

This interview, conducted in 2003 for the magazine Simulacres, was published as ‘Identifications du peuple’ in ‘Et tant pis pour les gens fatigués’ (Éditions Amsterdam, 2009).

How do you explain that the “people”, at the moment when it takes on its modern sense, becomes such a problematic object of representation, propitious to all ideological projections, and major issue of controversy, politically as well as esthetically?

The people has always been a double figure. At the time of the French revolution, it emerged in the opposition between subject of sovereignty and actual population: miserable people or ignorant and fanatic populace. But this duality is still much older. Aforetime the demos in Athens referred to both the sovereign people of the Assembly and the clutter of common people. Democracy is first of all a sobriquet invented by the Athenian elites to designate this inconceivable government of common people. Each time the people is declared sovereign, the same fundamental paradox, under diverse forms, makes the scene. The people as political subject is an entity which is supplementary in relation to the count of the population or any of its parts. And nevertheless it’s bound to the homonymy with these sociological figures of the people, as formless mass, miserable population, repertory of picturesque features, etc. There are several ways to deal with homonymy: we can search for identification, in the manner of Michelet*, endowing an abstract people with a substantial reality – which instigates a contestation about the “good” identity. On the other hand, we can also conceive it, in the manner of Marx, as a sign of lies, and at the same time denounce the illusion of ideal sovereignty and all figures of identification, Social Contract and The Mysteries of Paris*. In any case the “representation of the people”, that is to say the regulation of the distance between the “inconsistency” of the people as political subject and the sociological consistence of popular embodiments, becomes an essential issue.

There is no “real” people which could object to false images by way of its physical evidence. The people as subject does not have a body but only plots, discourse, mise-en-scène. The elaboration of these manifestations of the people presupposes a whole game of differentiations, imaginary negotiations with figures of the people, between embodiment and objection. The question of the representation of the people understood here belongs to the aesthetics of politics, to its undertaking as re-figuration of sensible givens. But this question necessarily intersects with that of the politics of aesthetics. The time of the French revolution and social emancipation is also that of the aesthetic revolution which dispenses with the old representative canons, defining what had to be represented and how. It’s the moment when the repartition of genres, styles and characters as either noble or vile dissolves, when the genre of amalgamation – the novel – takes power in literature, when genre painting emerges as the veritable “painting of history”, etc. The “low” genres had always lived off the crossing of heterogeneous worlds and picturesque effects of popular types. The so-called “realist” novel puts social diversity in the foreground of the literary scene – this popular exotism which was previously confined to the comedy of manners or the picaresque novel. But precisely this foregrounding entails that the representation of the people itself becomes an aesthetic problem, accompanied by a reorganization of the relation between narrative and descriptive, as well as the relation between fiction and signification. This reorganization takes place between two poles. On one side, the ancient differentiation of the noble and the vile is displaced within the represented people, so that the people at the same time furnishes the central dramatic figures, battling against destiny, injustice, etc., and the picturesque or villainous background. This is the Hugo schema*. On the other side, the equality of the noble and the vile is translated in the equality of narration and style, embroiling the moral and social distinctions in their indifference. This is the Flaubert schema*. The attempt of a “critical” representation of the people has always been a negotiation between these two schema’s of redistribution of equality: heroic differentiation on one hand, subtractive indifference on the other. The problems put forward by the regulation of this polarity thus converge with the political problems of the regulation between political subjectivation and figures of social identification, without there being a measure of the “good” proportion between these two relations.

You often tackle the question of the representation of the people hinging on a type of story that you call the “visit” of “voyage” to the people. In what way does “the people” appear as being always elsewhere, never already there, necessarily implying a journey to meet it. Is the people always to be understood as the figure of the Other?

Here it’s about the people as this figure of the social imaginary in which we can differentiate the political or artistic constructions of popular subjects. This representation of the people has often occurred as a game of back-and-forth between the same and the other. On one hand, there was a wish to mark and eventually fill the distance between the political people and the “real” people. This involves all the voyages destined to meet the real people, to instruct them or report their testimonies to the administrators and representatives of the political people – whether to warn them for the dangers threatening them (Balzac’s rodent peasant people) or to call to mind the tasks they are responsible for (Hugo’s visit to the “caves de Lille”). In this case, it’s about affronting the otherness of the sociological people in relation to its political identity. On the other hand, the people appeared as the identitary figure of the embodied concept. So the men of representation – of otherness – went looking for this people as themselves, guardians of a lost identity. One has to travel in space and often in time to regain this identity. The Same, the body assuring significations by their embodiment, can only be found in the land of the Other. Here again the political game with the gap making up the people converges with a game which is more properly aesthetic: the voyage crossing worlds and types is a narrative paradigm of which the constraints and forms mix with the political issues of the same and the other.

Besides, to clarify, do you distinguish “visit” and “voyage”, associating the first with the voyeurism of social tourism?

What distinguishes the visit from the voyage is a principle of economy. The visit adheres to the recollection of the features that are necessary and adequate to characterize the object of danger, concern of curiosity. The voyage exposes itself to the risk of not coming back, or coming back after having lost the marks of identity and otherness. Of course, the borders are not watertight: for some, the Saint-simonian visit described in the Short Voyages to the land of the People is transformed in a voyage without return*.

According to you, how does cinema resume, displace (in relation to its literary origins) and figurate the encounter with the people? In regards to this subject, you have focused on two conditions which are necessary for the representation of the people in cinema, without resorting to iconic attributes and accessories, symbolic codes and linguistic accents: on one hand, the confinement of the crowd framed in the image; on the other, the introduction of a principle of contradiction. What can be the agents of division operating in the “film fables” of the people?

Cinema has developed as a narrative art and, as such, it has naturally resumed a certain number of standards from narrative art in general: problems of identification and diversity, of typecasting and amalgamation of genres. But it is also a visual narrative art, an art in which recognition functions mechanically and which is imperiled by its excess of sensible information. It is thus constitutionally threatened by immediate identification with the stereotypes of social imaginary and had to, in order to differentiate itself, propose more sophisticated narrative and visual representations. At the time of silent cinema, one could work with the autonomization of the visual to topple over heroic representation in the fantastic and the mythological. It’s the formula of Eistenstein, particularly in Staroye i Novoye: here the formula with which Zola had mythologized the Halles or the grand magasin is applied to the Kolkhoze. With the constraint of concordance in the talkie and the entailing addition of realist information, one had to conduct a game more in line with the resemblance. This is what I evoked in relation to Europa 51: the necessity for Rosselini to choose formal criteria discarding the forms of vestimentary, gestural or linguistic typification of the popular.

The representation of the people involves a certain negotiation between individualized figures, bearing characteristic social features and engaged in conflictual scenarios, and the forms of non-individualized or semi-individualized visual presence of a community, most of all presented by the frame, by the effects of density or the forms of displacement and differentiation it enables. The courtyard of the apartment block is in cinema what the antechamber of the palace was in the classical tragedy, in the way in which – by making the places communicate and the characters circulate – it assured these individualizations and desindividualizations. In the launderette or the printing house in Le Crime de Monsieur Lange there is always – by way of depth of field, tracking shots or just the simple effect of cutting static shots – this referral and this game of transitions between the collective and the figures: identified and non-identified bodies between which one has to slalom in the atelier, groups individualizing visually in reaction to the events of the action without being individualized fictionally (the workers at the windows to whom the camera ascends while Lange unnails the panel). We could thus speak of a presence of the collective as such, which doesn’t identify with the accessory role of “extra’s” nor the harmony of the opera choir. And we can put it in analogy with certain forms of relation between political subjectivation and social imagery. So in Renoir’s films, the relation between the people as collective of life and the atelier as place of class conflict would correspond to a a certain political figure of the worker as subjectivation of the people. And the visual relation of the individual with the collective would be a kind of analogy with militant activity, made out of individualizations in the name of the collective. But the concordance is always fragile, the distinction between the active collectivity and the choir of extra’s is always near vanishing.

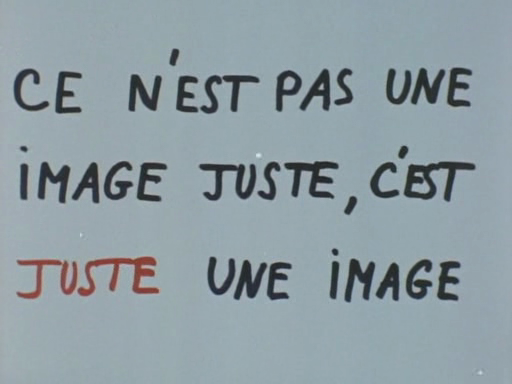

So how can we recognize the image of a “good” people or the “good image” of the people?

There are no criteria of accordance between political, social and fictional figures. There is no “good representation” for the simple reason that the political people does not consist anywhere in its identity. There are representations that come rather close to making this gap, in relation to every simple identity of the people, sensible. For example, the “contradiction among the people” is a classical form of this distance within the people which does not only exist in cinema but which finds a condensed cinematographic figuration in Europa 51, when the prostitute neighbor barges in the workers apartment or when the filmmaker blurs the topographic marks of the visit in order for us to meet a figure – Giuletta Masina – who blurs the image itself of the worker. Precisely, there is no good frame. The framing of the large family in a little space is a cinematographic invention opposing the simple illustration of popular types. It’s the frame of a “first visit” taking on its value by being undone by the wandering journey of the heroine. What matters here is the material acceleration of a process of disorientation of the visitor, it’s the relation of the compositions and decompositions of the popular frame with this acceleration. We can verify this in seeing what happens when the “deviant popular figure” is immediately given as illustration of an already given opinion matter. The Nadia in Nadia et les Hippotames provides the perfect illustration. It is a -nth imitation of Giuletta Masina. But it’s an imitation making the journey in reverse, taking back the cinematographic figures to the social imaginary.

What makes the difference are thus not the “images” in the conventional sens, not the states of present bodies, but the composition of the pathways they cross. That’s where the effects of aesthetic mobilization play out. Take for example a film “about” the people, most certainly not very popular in the ordinary sense of the word, Béla Tarr’s Satantango: what is prodigious here is the mobilization and the cast in the unknown of bodies which seem to be plunged for ever in the torpor of an immobile rural world. There’s a bit of the same thing in the first two parts of Bill Douglas’ trilogy, in which a miserable childhood is like described twice: statically and dynamically. We can also think of the reversals of the figures of the “dominated” put in place by the Straubs: for example the crescendo of the sequence in which the mother in Sicilia ! visually and vocally overturns the character of woman-victim.

There is little point in asking how these identities can be represented. What is at stake are the processes of subjectivation, of recomposition of spaces and times. It’s here that the challenges of the relation between politics and narration – filmic or otherwise – are situated, and not in the question of the differentiated representation of the people, the worker, etc.

Regarding the challenges of the relation between politics and filmic narration you have posed the question of the people in cinema hinging on a critical analysis of the French “dominant fiction”. You have reproached the “fiction of the left” of having promoted in 1975-1980 a commemorative “voyeurist-unanimist” spectacle of the people at odds with its genealogy. Then you reproached the popular commercial cinema of the 1980’s of having produced moral distortions in the name of the social victims of the system, and more recently you reproached works full of their “realist” subject of exceeding the “Bovary effect” for ideological ends. Why is French cinema condemned to only express a “caricature tyecasting” of social identities when it takes the people as subject of fiction?

I don’t think there is fatality weighing on French cinema, even if one is not without impunity a citizen of the country that produced Les Mystères de Paris, les Misérables and L’Assommoir. There is at the same time the weight of a tradition and the weight of the attempts of escaping it, of populist representations, their criticism and the criticism of this criticism. The “voyeurist-unanimist” cinema of the 1970’s was also the product of this complex dialectics. Those who made it, but also those who – like me – criticized it, had lived in the intellectual atmosphere of the 1960’s. Marx, Barthes, Brecht and Eisenstein had taught us to oppose the rigor of the concepts of revolutionary theory to all the heroic representations and all the picturesque typologizations of the people. Around 1968 we’ve had the feeling that the hard-line proletariat, in the name of which we had learned this disdain for popular figures, was a fiction, at once politically deceptive and artistically impoverishing. This feeling has nourished the political will to regain a “real” people and the artistic concern to propose popular figures who at the same time revive a certain tradition (the people of Les Misérables or Crime de Monsieur Lange) and emphasize the marginal figures suspected by the marxist tradition: the vagabonds in Le Juge et l’Assassin, farmers with devouring sexual energy in La Communion solennelle, marginalized workers in Bof etc. It was also the era of Cheval d’orgueil, Montaillou – Village Occitan and an extensive ethnological literature re-staging a true, colorful and turbulent people, opposing its physical evidence to proletarian theory, but also ready to offer this flesh and blood to the official left: the “sociological majority” Mitterand claimed to embody in 1981.

In retrospect, how do you perceive this severe interpretation of the history of the representation of the people by French cinema since some thirty years?

The criticism I could make at the time is without a doubt a bit simplistic, in playing on two levels: on one hand, It opposes to the picturesque sociologism of the representation of the people “à la française” a “historical” sense of the nation’s formation, typical of American cinema. When we now see the forms of amnesia stemming from the “historical sense” of the official America, one has to say that it is above all a moralist tradition opposing the sociological tradition. On the other hand, the criticism of this “sociologism” suggests that there could be a good way of representing the people, a way of escaping typification, without mentioning what this way consists of. In this way it continues the Marxist and modernist tradition of suspecting the narrative: as if all narration was directly part of the political mystification when appealing to categories of high and low, center and periphery, identity and otherness. Yet the narrative always needs such topographies that will always be ambiguous towards politics, because the narrative has its own politics, just as politics has its aesthetics. It’s easy to negatively point out the convergences between the flaws of political subjectivcation and those of artistic fictionalization: indeed, one and the other meet each other in the same incapacity of transforming the social stereotypes of representation. But there will never be a coincidence between a good politics and a good cinematic or literal representation. Nonetheless, there are narrative politics procuring works that are more or less free or subjugated to the official imagery. And this servitude is at the same time aesthetic and political. In this sense, the diagnose on the way in which this cinema of diversity appeals to the Mitterandian unanimism seems to me altogether verified.

Your observation originally articulated with a very critical perspective on post-1960 leftism. Moreover since 1977 you have been pointing out the necessity to compose its history in order to discern the “anxiety” that accompanied the “visit to the people”. Confronted with the evolution of the political culture of the left, which incidences do you see in regards to the representation of the people?

When socialism was in power the naiveties of the leftist voyage effectively shifted to the trickeries of the picturesque visit to the margins and the slums. And with the collapse of this socialism a certain ambiguity introduced itself: on one hand, there is a return to a traditional working class people that was declared obsolete in the preceding period. The working people par excellence, the workers of the North, returned in full force in La Vie Rêvée des Anges, Ma Vie de Jésus, L’Humanité, La Promesse, Rosetta or Selon Mathieu. But this return of the repressed is set in a frame in which one doesn’t know very well how to tie narrative dramaturgy together with social narration. The conceptual/visual frame that, at the time of the Front Populaire, reconciled the imperatives of fiction in the studio with the topography of the class struggle, belongs to the past. They are replaced with wide shots, open landscapes and the wanderings of the road-movie, in the wider sense of the word, and with them, we’re having trouble to reconstitute the entanglement of the plastic, the narrative and the political that worked well in the 1930’s. The flamboyant exception of the 1980’s is still Une Chambre en Ville, in which the formal constraint added to the fiction by the music, transforms, without the mediation of any sociological imaginary, the streets into an opera scene, all the while recreating a possibility for coincidence between sensible and political intensity: notice how the sound of the gong sets the tone for – in my memory – this choir of marine blue policemen behind their shields demanding the demonstrators to disperse. So it’s not the people anymore but the class struggle as such that is figurated in its legendary and sensible dimension.

How do you understand this category of “social cinema” which is fashionable since about fifteen years ? How to interpret this expectation, this demand for an “authentic” social cinema that would be “the source of a liberator’s vision of humanity” hinging on a “critical reading of society”?

In the idea of social cinema there is, I think, the idea of finding an accordance between a cinema taking as objects social situations or conflicts, a cinema apt to nourish a critical analysis of social relations, and a cinema in full measure, that is to say defining specific forms of this connection. Once again, there is no “good formula”. In the name of fragmentation, we dream of an ideal agreement between the declension that is supposed to be typical for the aesthetic modernity and the significant connection that is supposed to be typical for social criticism, a sort of conjunction of the Bovary effect and the Cosette effect. The physical relentlessness, the cluttered image and the syncopated rhythm of Rosetta arguably provide the exemplary formula of this conjunction. We can interpret this, as I try to do, in terms of differences of narrative and signifying speed. But the notion easily becomes a magical password transforming the desire to find the conjunction between fusional identification and critical distantiation in the reality of this formula. The fragmentation is a narrative procedure that can either rigidify narration, undo it or produce ruptures bearing sense, or cancel the sense in the juxtaposition of elements.

If we look at the diverse formulas that are today taking on the representation of the people, we notice on one hand an effective will to visualise a world of class struggle buried by consensual discourse, on the other a difficulty to narrate it in the classical form of the narrative of injustice and consciential awakening. Some connect the social drama to a problematic of identity and filiation (La Promesse, Selon Mathieu, Ressources humaines), with the risk that one of the two affiliated scenarios would denounce the other as subsidiary. Others try to relate its representation to a supposedly popular form of narrative: the courtyard in Marius et Jeannette tries to recreate the privileged decor of the unanimism of the Front Populaire. But on one hand we feel that the post Nouvelle Vague cinema has trouble with spaces à la Renoir: the fiction and the camera scuttle off, as to their natural habitat, to the roads and the waste lands denouncing the enclosing of the “popular” frame. On the other hand, this fictive operetta decor suits the bodies of the characters as long as they are popular theater types. In return, the dispositive collapses when the decor is connected to the outside, when the dramatic types are characterized as representatives of political forces. Darroussin has in fact become a character of commedia dell’arte in which the label “front national” is felt as purely artificial. Others try to topple over realism in the oneiric: in De L’amour, in which the “narrative of the banlieu” is first worked out according to a traditional schema (the small theft has as consequence the encounter with the repressive system and the horror of rape), but tipples over in oneirism in the following stage (the chase of the rapist policeman).

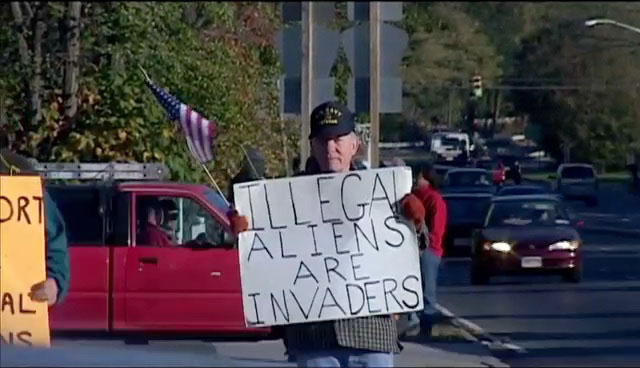

Do you think militant commitment can nowadays only give voice to the people under the form of documentary?

The contemporary interest in documentary responds to this difficulty. It translates a certain helplessness in regards to so many possibilities of fictional presentation and political narrativization of what’s happening today in the so-called social domain (unemployment, immigration, violence, ..). The documentary amounts to a testimony at least attesting to the fact that the working class, the class struggle etc. still exist no matter what the dominant discourse says, in spite of the impossibility of finding new narrative schema’s. On the other hand, it responds to the fact that the invention of the real, meaning the capacity of reorganizing the given, to vary the indicators of reality and the potentials of signification of signs, is today a domain that offers more to creativity than the adaptation of fictional schema’s to new realities. It’s a phenomenon that goes beyond cinema. The places of art establish themselves more and more as places of another form of information, of another way of establishing the fabric of a common real.

To what extent are your preoccupations with the fiction of the people in cinema in accordance with your theory of the “aesthetic regime of arts”? Can a film at the same time claim the aesthetic tradition of cinematographic “modernity” and militant sensibilization? How to understand the depolitization in regards to cinema, whether it results from an indifference, even a critical disdain for social subjects, or a “humanitarian” transcendence of problems of community, or a distrust of the lies of narratives and images?

I think we have to reformulate the question of what we expect as political effect from a fiction. The problem is not, as we say, to know whether art and politics have to connect to one another. It’s that politics has its own aesthetics – its way of establishing a common scene, including certain objects and subjects, scenarios, continuities and discontinuities, etc. However, aesthetics also has its own politics: its way of cutting specific time-spaces, populating them with certain types of individualities, making the topographies and causalities work, etc. Aesthetics of politics and politics of aesthetics move together, but are not in accordance. The era of political revolutions was also the age when literature revoked the representative hierarchies of noble or vile subjects. But the literary equality breached the plane of consistence of democratic political subjects and became interested in forms of microscopic individuality and forms of linking events escaping all causal explication and all pursuit of ends. It’s in the sense that Flaubert once declared to be less interested in the poor than in the lice devouring them: less in social inequality than in atomic equality. But even in Les Misérables, in which the same Flaubert sees socialist demagogy, the political finality (Enjolras) is ruined by the drifting journeys winding up on the barricades where the children of the street and the slums (Eponine and Gavroche) meet the outcast (Jean Valjean), the drunkard (Grantaire) or the man without purpose (Father Mabeuf). Literature only accompanies the political novelty by the establishment of a fantastic topography: the mythological voyage in the social depths at the same time supporting and denying the scene of utterances and political manifestations.

So between the political and aesthetic mise-en-scène in the era of the aesthetic regime of the arts, there are only partial encounters, mobile negotiations, ambiguous identifications etc. There is no reason for the political people which, in sensu stricto, does not exist, to find its accordant representation in such a narrative intrigue or such a cinematographic body. A film is always a certain equilibrium between narration and visuality, at the risk that the visuality would submerge politics in the imaginary of types or eschews it in the indifference of the represented, or that the narrativity submits politics to emphatic identification etc. The dionysism of Staroye i Novoye has been deemed reactionary formalism in the USSR before being identified elsewhere as a display of Stalinian propaganda. The stories of chaos that are being told by American cinema since thirty years can be understood as a denunciation of this society, but also as a denunciation of all will to politically rationalize the violence inhabiting it (which is still today the lesson of Mystic River*). A slight displacement of sensibility and argumentation is always enough to deem La Belle Equipe, La Terra trema or The Grapes of Wrath – just as les Misérables or L’Assommoir – exemplary militant works, socialist demagogy, reactionary idealizations or bourgeois aesthetization of misery. Some are nostalgic for a supposed accordance between the Front Populaire and the films of the times of Renoir, Carné and Duvivier. But it’s the Front Populaire that has politicized the meaning of these films more than they have contributed to the political mobilization of the time. This means that there are no theoretical concepts or political credo’s on one side and on the other narrative fictions of which we wonder whether or not they are in accordance with hem. There are just several sorts of topographies and narrative constructions interweaving with eachother. It’s up to politics to take a hold of these forms of refiguration produced by the arts for their own constructions. One has to stop thinking the relation the other way around.

You seem to give more credit to the “frank return” of a stereotypical iconography of the dangerous and rough “coarse brutes” in L’Anglaise et le Duc, than to the “supplement of soul” in La Vie Rêvée des Anges – the dreamed life of angelic representatives of the people, according to a fine rupture with the ”social coding” which only reinforces it. To put it another way, we don’t understand very well your rejection altogether of sentimentalism, as if in a French context, every character who would encourage identification for the spectator would be susceptible in the name of the people. To what extent can the criteria of appreciation (affective, ethical) not be taken in account?

I absolutely don’t reject sentimentalism nor identification and i don’t judge things according to a simple criterion of coherence. I share without any reservation the grief of the little Huw Morgan returning from the mines with his dead father (How Green Was My Valley) or that of The Tramp whose adoptive son is taken away from him (The Kid). But Ford fully plays the game of coincidence between the fictional arbitrary (the small village visibly recreated in the studio) and the double register of sentimental melodrama and social drama in which natural catastrophe is as probable as class or generation clashes or the impossibility of love. Conversely, Chaplin’s cinema is founded on a dissociation automatizing the maximum of behaviors and expressions, at the same time creating formidable accelerations of emphatic emotion. But the fictional naivety hardly works anymore: since there are no more workers descending in the mines, we want to see real mines on screen. And perhaps the secret of the union between the mechanical and the living also belongs to this era of the class struggle’s brutal visibility. With the same cumbersome baby as in the The Tramp’s arms, the character in Pedro Costa’s Ossos sinks in the mutism of a world where the resistant border of social division cannot be figurated anymore: proletarians have become outcasts, the hospital and social assistance have replaced the police and the prison as figures of encounters between the two parts of society.

So it’s not me who rejects sentimentalism. It is sentimentalism which – in the double sense of the word – doesn’t hold up anymore. On one hand the narrators and the spectators have become too clever. They are wary of the affective and prefer the neutrality of the sensorial. They are also wary of morality and prefer the game with social codes. On the other hand, the forms of visibility of social conflict are now wrapped up in something else: for example, problems of identity. The politics of the clever wants to kill two birds with one stone: to supply the emotions of a popular body while showing that one is not taken in by it, playing out one people against another. Take for example La Vie est un long fleuve tranquille. The film is for me like an illustration of Bourdieu at the time of La Distinction*. To the glorious people of the intellectuals and the militants, it opposes the quite sordid reality of this typically French cunning family. And conversely, it gives the family the attributes of vitality shattering the social games of distinction and the veneer of social respectability. The success of the film has ensured that a “popular” audience is now an audience capable of playing this double game itself, while taking the pleasure that one earlier took for sentimental identifications.

The double relation is more complicated in an aesthetically ambitious film like Bruno Dumont’s L’Humanité, which no longer plays on two but three levels: cutting in the gengiva of good progressive souls (your people is like that); aesthetic identification (the film identifies the glorious silence – the absence of signification – of the work of art with the brutal mutism of the policeman with aphasia and the couple of sexual animals); and spiritual testimony on the state of humanity.

In regards to Godard’s films, you seem to regret a certain melancholy related to the absence of a resistant body, in particular in Eloge de l’amour. What is a resistant body – and a resistant body encouraging an identification for a community of public? What are the links between the people and the community in cinema, in the fiction mode as well as in the domain of social practice? It would seem that you nowadays, in relation to political cinema, only salvage Straub and Huillet.

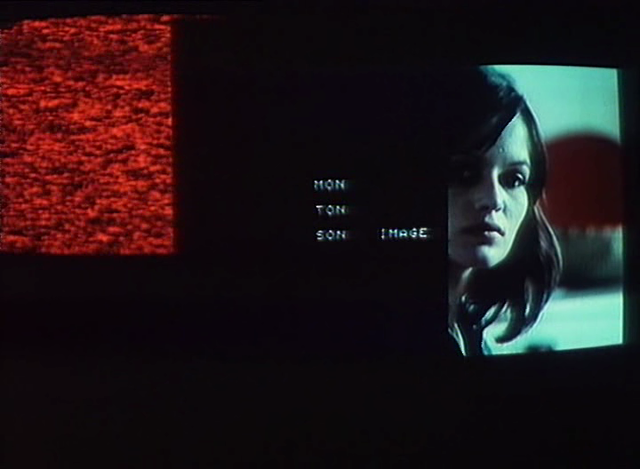

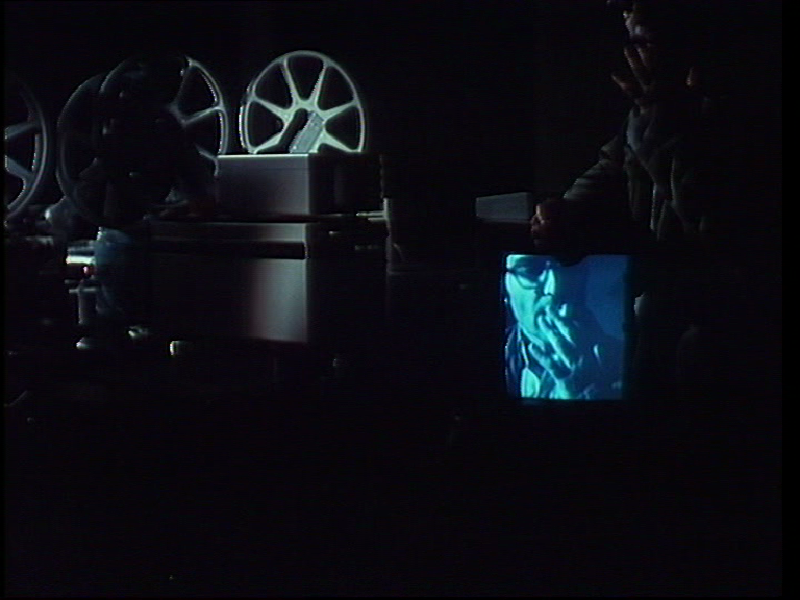

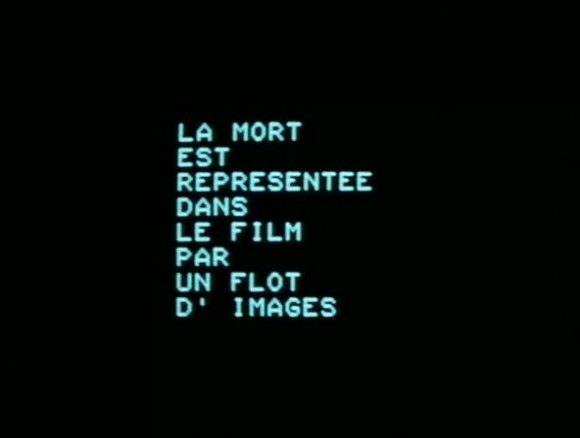

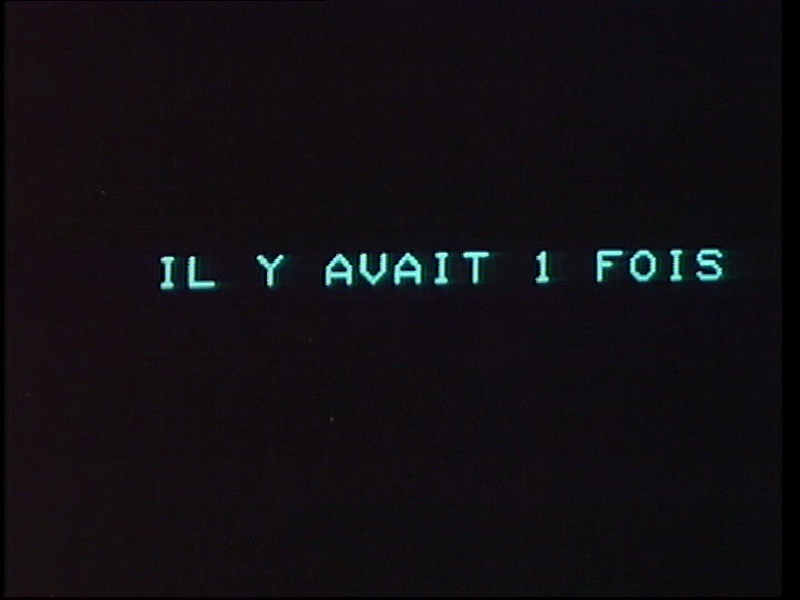

The problem is not to save or to condemn but to identify the politics at work in a film. Seen this way, L’Eloge de L’amour and Operai, Contadini are two symmetric fragments of an avant-garde tradition linking political purity with a refusal of narrative. Godard entrusts to the rigor of art the care to point out the empty place of the people: the abandoned island of Seguin, the deserted workers canteens, the night cleaners of trains without conductors or passengers, or the home-less refugees. He thus also plays with a certain accordance between refusal of narration and this essential absence. The Straubs’ films render the people present by the elision of narrative, by constructing a sensorial dispositive which embodies what is associated with popular and revolutionary signifiers. It’s about establishing – between body and sense, between what is said and what is made visible – a direct relation that undoes the imaginary fictionalization of social bodies. These bodies, seized in their actuality, are placed in direct resonance with a literary text that speaks about the people, class struggle, Communism or simply the earth.

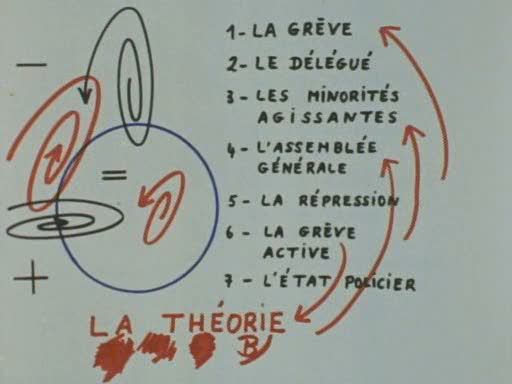

In 1976 you launched a call in reaction to Godard’s Ici et Ailleurs: “This is the time for dialectics. How to divide, who unites and on the basis of what?” Fifteen years later, Straubs’ Operai, Contadini offers a reconciliation with a suspended movement of the visible, while embodying the division of the people hinging on a “dispositive of talking bodies”. Considering this brutal confrontation, can we talk of an aesthetic evolution, as you have proposed recently, from “dialectical style” to “symbolist style”, to justify the heterogeneity of the represented people?

Indeed, the meaning of this relation has changed since the 1970’s. Back then it was conceived as a sort of Brechtian exercise. In Geschichtsunterricht the dialogue of the antique Roman senators talking about on the affairs of Mister Julius Caesar, set in a contemporary villa, figurated the paradoxical scene set up to produce a double effect: an effect of truth, revealing the law of money supporting now as then the big politico-military enterprises, and an effect of educating, learning the dialectical operation of arguments. In their recent films, the element of dialectical quarrel is always present: the farmers and workers in Operai, Contadini affirm the people by affirming its division. But this affirmation and this division tend to change meaning. What matters now is the way in which these bodies directly embody the force of communist affirmation and revolutionary refusal. It’s not so much anymore about learning to read the contradictions of the class struggle than it is about affirming, as a radical challenge to the existing order, a popular capacity for resistance and edification of a new world. At the same time this radical refusal tends to inscribe itself in a global movement of contemporary art, fitting yesterday’s dialectical provocations in a concern for constructing new forms of symbolization of communal history, to “give back faith to the world” (Deleuze). Hölderlin has taken the place of Marx as thinker of communism. The challenges of class struggle have become those of the defense of the earth.

This said, I don’t think at all that the Straubian formula is the only formula for a political cinema today. A filmmaker like Pedro Costa, who’s very close to Straub, produces a cinema which is quite far away from this heroic posture. It’s about plunging into the very heart of the demolitions of communities and the destructions of communal languages, attempting to bear witness in the most material way to the demolition of forms of life and fragmentary words trying to maintain destroyed lives on the level of sense and individual appropriation, even minimal. Here again, what matters are the relations between spaces and temporalities: in No Quarto da Vanda, the way in which the time and repetitive wordings of the poor and lost are confronted with the speed of the machines of destruction and the way in which they constantly transform the inside and outside.

Do you envisage the possibility of a political or militant cinema that is at the same time popular?

Of course none of these films are popular in the current sense of the word. But which narrative is popular today? The familiarity of self-images and the strangeness of special effects in fact tend to divide (se partager) what used to be the domain of the popular narrative.

What is considered as the political criticism or appreciation of a film is always a relation between two things: there is the aesthetic politics of the film, its capacity to shatter the stereotypes of representation, to reconfigure the forms of the visible and thinkable, the modes of representation of situations, linkings of events. And there is the relation of this intrinsic politics to a certain horizon of possible politics. Take for example two authors belonging to the postcommunist world, Kusturica and Béla Tarr, each telling a story of swindling, establishing in a way the link between the regime of today and that of yesterday. The first, in Black Cat, White Cat, re-codes the forms of recomposition of a system in the stereotypes of gypsy jeering and cheering. The second, Satantango, restages at the same time the naked dereliction of a condition, the fascination of an ideology and the forms of manipulation that this fascination authorizes. I find in Satantango a real aesthetic politics and a moral honesty that is totally lacking in Black Cat, White cat, but I don’t think that one benefits more than the other today’s democratic fight in the East. Political efficiency of forms of art: it’s up to politics to construct it in their own scenarios.

Could you come back to this idea you’re defending, according to which the American “dominant fiction” has given rise to a cinema in which the people takes shape based on gestural inscription, bearing a communal questioning of American society? But which American films have, after the fracture of the 1960’s, revisited the American legend in the critical mode, up until the point that they could no longer reinvent themselves except for staging the ruptures traversing the social body? Have you seen and liked films that narrate the origins of America as the basis of an impossible reconciliation to come? The founding territorial conquest of the political history of the US imposes an image of the voyaging and “pioneering” people, retracing a movement of an offensive occupation. If it’s typical of the American people that they always have to conquer space in order to define themselves, how do you analyze the crisis of the mise-en-scène in American cinema since the 1970’s, endlessly chronicling aimless wanderings and voyages without destination in which the heroes are condemned to fortuitously repeat the gestures of the pioneers in an already occupied world? Do the pathways taken in this cinematography lead to the arousal of a novel voyeurism in regards to a people left on the road and encountered by accident or circulation – such as “red necks” or “white trash”, often caricaturised as primitive and savage communities? How do you perceive the gestures of violence of the legendary people adrift?

It’s clear that my valorization of the American legend, against the sociological typing “à la française”, was a bit biased. It mixed different era’s: that of the narrative forms of Hollywood – even “modern” – westerns and that of the problematic conjunction between post May ’68 and post Nouvelle Vague. It’s also clear that the American cinema since the 1960’s has shattered the heroic or unanimist images of the national legend, staging, instead of the narrative distribution of roles and routes (Indians and Yankees, representing order and outlaw, sedentary and adventurous etc.), pure relations of force, wandering journeys or naked violences: the tourists in Deliverance no longer meet Indians or bandits on their “river without return”, but only morons and sadists. But precisely this new American cinema of the 1970’s bears witness to a historical gap. Held in place for a longtime by the Hollywood formatting cut off from the romantic revolution, cinema has after forty years rejoined the fragmentation of the narrative à la Dos Passos*. Romantic fragmentation in the 1930’s was of course linked to an acute consciousness of a social universe structured by class struggle. Yet it has won over the cinema at the moment of the offshoot of the great fights of the 1960’s (civil rights and Vietnam). All of the sudden, the demystification of the legend has signified the global opposition of the theater of political significations to a true world which is pure chaos. It’s the fable of Taxi Driver, opposing the wanderings of the driver whose car transports or happens upon figures of chaos, to the parades of the campaigning senator and his slogan “we are the people”; or it’s the “God Bless America” concluding The Deer Hunter, rendering the utterance of patriotic faith and the music of dionysiac non-sense absolutely equivalent.

This way every communal history finds itself returned – including through the concern of historical accuracy itself – to a “history of noise and fury told by an idiot”. This is exactly what is happening in Cimino’s films. In Heaven’s Gate, the glorious conquest of the West is returned to an episode of ferocious class struggle in which the rich use a group of mercenaries to get rid of the poor settlers. In a way, it’s the scenario of Grapes of Wrath radicalized by reversal. But precisely this reversal immediately installs us in a universe denying the scenario of “consciential awakening”. When Cimino wants to individualize in conscious figures this group of emigrants represented as compact masses and primitives who only get excited by cock fights, we sense the artifice. To this primitive horde, talking a strange language, corresponds a certain use of time interlocking the narration in endless sequences of genre scenes (marriages, all sorts of entertainment, scenes of collective deliriums) to return the strictly speaking “narrative” elements to accelerated and quasi incomprehensible episodes of violence.

The Russian roulette which, in The Deer Hunter, substitutes the war as process of extermination, makes itself known as the symbol itself of narrative parataxis. The narration indifferently carries along the elements, just like Taxi driver indifferently transports his clients. Genre scenes and outbursts of naked violence replace all linkings between a narration and its meaning. Following Schopenhauer’s logic, it’s the background noise of very elaborated musical scores that gives unity to the chaotic succession of images, conferring to these films their fascinating aspect of deconstructionist soap-operas. There is only the moving back and forth between the primitivism of parties and that of blood. This is again – but with strongly reduced aesthetic exigences – the principle of Gangs of New York, representing, in the milieu of calculating traders and politicians of he 19th century, a people seemingly coming straight out of Ivanhoe. The liquidation of rivaling religious hordes of axe meneurs by the troupes of the modern state only confirms a certain suspension of meaning. The “we are all immigrant children” of the political declaration is here reversed to a “we are all primitive brutes” which in the end abides in a relation of indifferent juxtaposition with the official hymns of the great multicultural nation of militant liberty.

It seems to us, listening to you, in particular about Cimino, that the representation of the people should be subdued to a principle of economy, of justness, of usefulness, for it not to be artificial. In which sense?

When I talked about artifice – in the case of Cimino or Guédiguian – I only wanted to question the coherence of a choice. According to me there is no general principle of economy. But it’s true that Guédiguian’s mise-en-scène is more at ease in a dispositive of comedy functioning according to a principle of stereotypy; it’s a mise-en-scène which begins to feel like artifice when it wants to turn these types of representing characters into forces that are either political or oscillating between political choices. In the same way, Cimino is first of all a genre painter: the ceremony, the game session, the hunting party, the popular ball and all the scenes bearing witness to an immediate adhesion to a world, to a condition – something like social vegetation – are those that suit his mise-en-scène. Making the individuals come out of the decor, individualize them, is a big problem for him, even for the “heroes”. There is all the more artifice when the men of the masses, presented as such, have to be individualized under the traditional form of “consciential awakening” of the oppressed. If there is a principle of economy, it’s in the sense that the determination of popular features does not have to block the process of mobilization, of transformation of bodies composing a political scenario. It’s a recurrent problem of the representation of the people: that the representation of a “popular” identity should not block the routes of transformation of bodies identified as such. The linearity of the Fordian narrative or, on the contrary, the narrative stasis of Bill Douglas or Béla Tarr attain this in different ways. But the baroque of Cimino is not appropriate here. By contrast, it perfectly suits the representation of a history cancelling itself out.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Translated by Stoffel Debuysere (Please contact me if you can improve the translation).

In the context of the research project “Figures of Dissent (Cinema of Politics, Politics of Cinema)”

KASK / School of Arts

translator’s notes

* Jules Michelet: prolific, passionately republican and highly literary historian, author of a monumental “Histoire de France”. Ranciere argues that Michelet invented a new way of processing the testimonies of those whose social position had not destined them to think and write, but that this was simultaneously a way of making them figure visibly in the historical narrative while silencing their own voices: he “invents the art of making the poor speak by keeping them silent, of making them speak as silent people”.

* * Eugène Sue’s novel ‘Les Mystères de Paris’, a successful mixture of moralizing melodrama and social criticism, was first published in 1842–43. The book was mostly praised for drawing the attention of the prosperous classes to the misery which they tried to ignore, amongst others in a periodical called ‘Die Allgemeine Literaturzeitung’, founded by Bruno Bauer, a leading figure among the “Young Hegelians.” The reviews were written by a young man called Szeliga, who took Sue very seriously, and sought to give his views the sanction of the Hegelian philosophy. Marx and Engels’ ‘La sainte famille’, published in 1845, was intended as a general attack on the ideas of Bauer and Szeliga. Two long chapters of the book, written by Marx himself, are given over to a destructive analysis of the moral and social ideals recommended in ‘Les Mystères de Paris’.

* The Social Contract is a foundation myth invented by Jean-Jacques Rousseau as a legitimation for the authority of the state. To this day, the “social contract” functions as a justification for the state and bourgeois social theorists try to justify various kinds of state intervention in terms of contracts supposed to exist between the state and its citizens, often advising states to renew the contract which was supposed to have been made in a mythical past, to establish legitimacy for its projects.

* Rancière: “There are two ways of thinking equality. It can be thought in terms of intellectual emancipation founded on the idea of man as a “literary animal” – an idea of equality as a capacity to be verified by anybody. Or it can be thought in terms of the indifferentiation of a collective speech, a great anonymous voice – the idea that speech is everywhere, that there is speech written on things, some voice of reality itself which speaks better than any uttered word. This second idea begins in literature, in Victor Hugo’s speech

of the sewer that says everything, and in Michelet’s voice of the mud or the harvest. Later, this poetic paradigm becomes a scientific one. The obvious problem is that these two paradigms, these two ways of thinking the equality of the nameless, which are opposed in theory, keep

mixing in practice, so that discourses of emancipation continually interweave the ability to speak demonstrated by anyone at all together with the silent power of the collective.”

* The core of the utopia spelled out in the 1830s by Saint-Simonism: “no more words, no more paper or literature. What is needed to bind people together is railways and canals.”

* In “the Ethical turn of Aesthetics and Politics”, Ranciere uses Clint Eastwood’s Mystic River as an illustration of what he sees as a problematic moralistic turn in contemporary American politics and culture that conflates victims and violators and advocates for vigilante justice.

* Bourdieu’s vision of the social world – described in La Distinction (1979), for example – is motivated, according to Rancière, by nostalgia for class struggle, and the desire to re-enact it. In its staging of social relations, the inheritors are characterized by ‘bad faith’ and ‘hypocrisy’, for they deny precisely that which is obvious. The poor, as the idealized and romanticized heros, appear somehow closer to nature, placing only use value on belongings, eating only to stave off hunger. Society is thus split into two camps: those who set out to distinguish themselves, and those who simply reproduce. Above them both is the sociologist, with the intellectual insight to know how things are, and the ethical superiority derived from dramatizing this truth for the dubious benefit of those who cannot grasp it or who repress it. In this respect, Bourdieu upholds the very hierarchy he describes, “granting [sociological] science a position of eternal denunciator of its eternal repudiation”

* Rancière sees in John Dos Passos’s perceptual reorientation project in the USA Trilogy of generating “fragmented stories of erratic individual destinies” an attempt to make the literary work a vehicle of criticism by welcoming “into its pages the standardized messages of the world”. As a literary strategy, Rancière rightly notes, this continues to be dependent upon the blurring of the “distinction between the world of art and the world of prosaic life” instituted by the artistic revolutions of the previous century. Yet the “montage of media stereotypes” in USA, “far from signifying the equality of all things”, is “in fact supposed to make felt the various forms of the violent domination of one class”. And while Dos Passos’s intent may thus have been to counterpose “the destinies of the characters and the discourse the world of domination conducts about itself”, ultimately the specific politics of literature that this proposes finds itself merely overtaken by that “impersonal force” of what Hegel called the “prose of the world”.

* Books mentioned: Les Mystères de Paris (Eugène Sue, 1842-1843), les Misérables (Victor Hugo, 1862), L’Assommoir (Émile Zola, 1876), Cheval d’orgueil (Pierre-Jakez Hélias, 1975), Montaillou, Village Occitan (Emmanuel Le Roy, 1975). For more on Hugo, Flaubert, Zola and Balzac, see Mute Speech: Literature, Critical Theory, and Politics, Politics of Literature and other works by Rancière.

* Films mentioned: Staroye i Novoye (Sergei Eisenstein, 1929), Europa 51 (Roberto Rossellini, 1952), Le Crime de Monsieur Lange (Jean Renoir, 1936), Nadia et les Hippotames (Dominique Cabrera, 1999), Satantango (Béla Tarr, 1994), My Childhood & My Ain Folk (Bill Douglas, 1972 / 1973), Sicilia ! (Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub, 1999), Le Juge et l’Assassin (Bertrand Tavernier, 1976), La Communion solennelle (René Féret, 1977), Bof … anatomie d’un livreur (Claude Faraldo, 1971), La Vie Rêvée des Anges (Erick Zonca, 1998), Ma Vie de Jésus (Bruno Dumont, 1996), L’Humanité (Bruno Dumont, 1999) , La Promesse (Luc & Jean-Pierre Dardenne, 1996), Rosetta (Luc & Jean-Pierre Dardenne, 1999), Selon Mathieu (Xavier Beauvois, 2000), Une Chambre en Ville (Jacques Demy, 1982), Ressources humaines (Laurent Cantet, 1999), Marius et Jeannette (Robert Guédiguian, 1997), De L’amour (Jean-Francois Richet, 2001), Mystic River (Clint Eastwood, 2003), La Belle Equipe (Julien Duvivier, 1936), La Terra trema (Luchino Visconti, 1948), The Grapes of Wrath (John Ford, 1940), L’Anglaise et le Duc (Eric Rohmer, 2001), How Green Was My Valley (John Ford, 1941), The Kid (Charlie Chaplin, 1921), Ossos (Pedro Costa, 1997), La Vie est un long fleuve tranquille (Étienne Chatiliez, 1988), L’Eloge de L’amour (Jean-Luc Godard, 2001), Operai, Contadini (Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub, 2002), Ici et Ailleurs (Jean-Luc Godard, 1976), Geschichtsunterricht (Danièle Huillet and Jean-Marie Straub, 1972), No Quarto da Vanda (Pedro Costa, 2000), Black Cat, White Cat (Emir Kusturica, 1998), Taxi Driver (Martin Scorsese, 1976), The Deer Hunter (Michael Cimino, 1978), Heaven’s Gate (Michael Cimino, 1980), Gangs of New York (Martin Scorsese, 2002)