In the context of the Courtisane festival 2013 (Gent, 17 – 21 April)

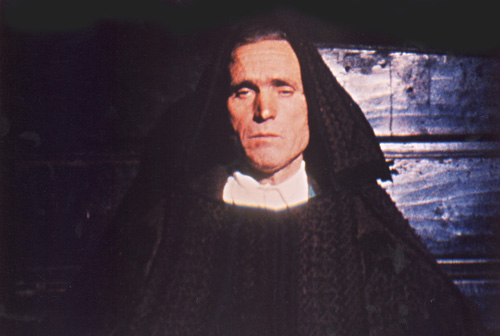

Resistance. If there is a single word that characterizes the work of Marcel Ophuls, this is it: resistance to every form of injustice and banalisation, resistance to the prevailing dogmas of documentary cinema. It is an attitude that is marked both by a whole-hearted abhorrence (for indifference) and by passionate love (for narrative film). The one is a response to his experiences during WW II, the other a legacy from his father, the famous director Max Ophuls. The result is an uncompromising cinema that for four decades has had no equal in blazing a trail through the 20th century’s shadowy realm: occupation and collaboration during the Vichy regime in Le Chagrin et la Pitié (1969), the Troubles in Northern Ireland in A Sense of Loss (1972), war crimes in Nazi-Germany and Vietnam in The Memory of Justice (1976), the siege of Sarajevo in Veillées d’armes (1994). Time and again, like a roguish Inspector Colombo, Ophuls makes his way through the heart of the conflict zone, in search of witnesses, in search of the story. Because Ophuls’s work primarily brings to mind the fact that the word “documentary” is always followed by the word “film”. This is a cinema that places structure above content, subjectivity above objectivity, discussion above pedagogy, a cinema that recognizes that documentary always equals “fiction” – a construction, a presence, a form. It is a cinema, finally, that refuses to make a distinction between “history” with or without a capital “H”, between a politics of the commonplace and the politics of the power apparatus, because that distinction, according to Ophuls, “forms the worst escape in life itself, the avoidance of every responsibility.”

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

KASKcinema Thu 18 April 13:00

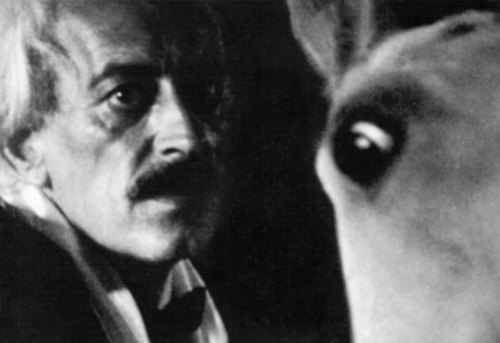

The Memory of Justice

1976, 35mm, color & b/w, various languages with English subtitles, 279′

The film uses Telford Taylor’s book Nuremberg and Vietnam: An American Tragedy as a point of departure in exploring wartime atrocities and individual versus collective responsibility. Divided into two parts – “Nuremberg and the Germans” and “Nuremberg and other places” – it builds into its very fabric the identity of the filmmaker. It’s not simply that we see him interviewing the subjects or feel his presence through intrusive editing; but Ophuls includes scenes with his German wife, his film students at princeton and even his grappling with cutting and arranging the overwhelming material. “I try to be autobiographical in Memory of Justice because of my wife’s childhood and my childhood – my reaction against what we feel has been misunderstood. I felt a great misunderstanding concerning The Sorrow and the Pity (the movie of my life, like Conan Doyle and Sherlock Holmes – I try to get rid of it, but it won’t go away): there is no such thing as objectivity! The Sorrow and the Pity is a biased film – in the right direction, I’d like to think – as biased as a western with good guys and bad guys. But I try to show that choosing the good guy is not quite as simple as anti-Nazi movies with Alan Ladd made in 1943.” (From an interview with Annette Insdorf, 1981)

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

KASKcinema Thu 18 April 22:30

A Sense of Loss

1972, 16mm, color, English, 134′

Preceded by a talk between Marcel Ophuls & Eyal Sivan (KASK CIRQUE 20:00)

Ophuls’s self-described “film report” on the troubles in Northern Ireland. “The structure of the film was to start with the investigation of death, death in all its forms – death by the bomb, death by the bullet, the almost accidental death – and then to set out in search of who the individuals were, what their favourite record was, their favourite film, where they wanted to spend their holidays, etc.. All this to give the life of an individual some sense. It is individualistic and anti-generalizing, and in that sense almost an anti-ideological film. Consequently, what it is about is not just the structure of the completed film, but most of all a structure of research. It was indeed the case that in the chronology of filming, the ambulances were followed first, with a system of having previously established signals with the police, with the people of the IRA, with the people of the British army in order to know where a conflict was underway, where violence was taking place, where there was death, and always being on the alert, even at night in the hotel, to be able to be there in five minutes. It was only afterwards that we tried to identify the people, and the historic reasons, the ideological, sectarian aspects of this conflict. It is therefore the research structure that determines the structure of the film.” (from an interview with Lorenzo Codelli, 1973)

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

KASKcinema Fri 19 April 14:00

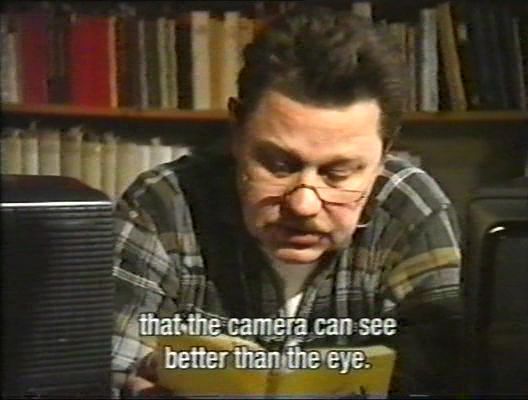

Veillées d’armes (The Troubles We’ve Seen)

1994, video, color, various languages with English subtitles, 234′

“Ethnic cleansing, that brings back memories,” Marcel Ophuls muses on the train to Sarajevo in this epic, ironic investigation of war and the journalistic impulse.. Ophuls traveled to the besieged city in 1993 to mingle with the motley crew of reporters camped out at the Holiday Inn; his interviews with French, British, American, and Bosnian journalists deliver trenchant observations on the political, ethical, and psychological factors behind the making of news. Other interview subjects include Serbian president Slobodan Milosevic, who claims his country’s freedom of the press is “unparalleled,” but says “don’t trust my explanation.” “I won’t.” Ophuls replies. Excerpting films by his father Max Ophuls, adopting the Marx Brothers as muse, the director employs a strategy of playful self-reference in the midst of horror; between feints at media and mediation, he moves in for a sucker punch of reality. As legendary reporter Martha Gellhorn, who survived both the Spanish Civil War and a marriage to Ernest Hemingway, puts it: “the brave are funny.” (Juliet Clark)

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

SPHINX Fri 19 April 20:00

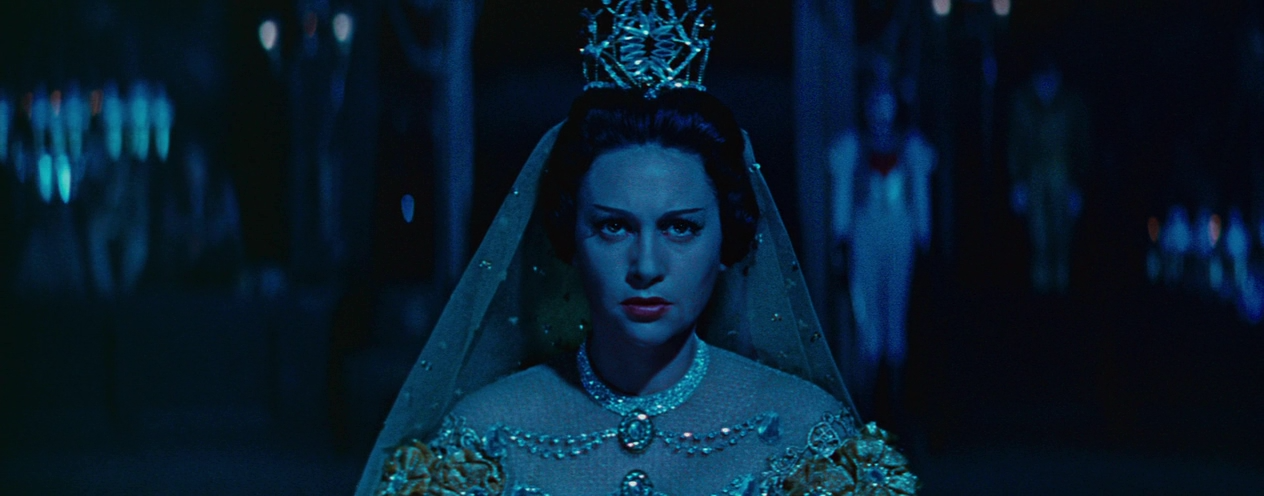

Max Ophuls

Lola Montès

FR/DE, 1955, 35mm, color, English with Dutch subtitles, 110’

introduced by Marcel Ophuls

Max Ophuls’ final film (and his only movie in color) is a cinematic tour-de-force masquerading as a biography, in this case a dazzling fictionalized life of the notorious 19th century dancer, actress, and courtesan. “Did his father’s reputation as a filmmaker help or hinder Marcel? “It helped me to get work. More than anything, it helped me to be modest about my achievements. I was born under the shadow of a genius, and that spared me from being vain. I don’t have an inferiority complex – I am inferior.” Ophuls worked with his father only once, as third assistant director on Lola Montès. “That means I was the coffee carrier.” It was his father’s last film, one the critics hailed for its ingenuity. In one shot, Lola arrives in a circus ring to re-enact scenes from her life while standing on a turntable that revolves in one direction, while the camera tracks round her in the opposite direction. “He was a genius, but that film killed him. I carried the coffee and saw him withering.” It was then Max had his first heart attack; two years later he died. “People say he was a romantic who dealt with private things like love and I was political,” says Ophuls. “That’s bullshit. I never make a distinction between private life and politics – that’s a petit bourgeois thing. How can you make a stand against Nazi Germany, or in Rwanda, when you live life by making that distinction? What I am saying has to do with citizenship.” (from an interview with Stuart Jeffries, 2004)