By Serge Daney

Originally published as ‘La radiation cruelle de ce qui est’‘, Cahiers du Cinéma no. 290-291 (July/August 1978).

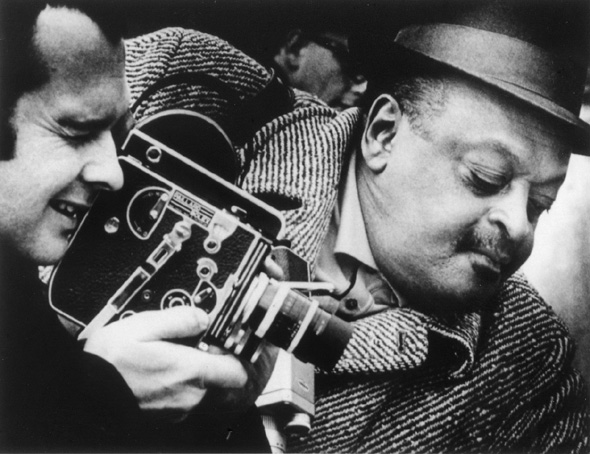

There are, properly speaking, no scenes in the films of JVdK, but fragments. Not parts of all that is to come and certainly not the pieces of a puzzle to reconstruct. But fragments of cinema, that is to say: carrying in them, with them, on them (that’s the whole issue) traces of a mining of the real, an imaginary operation of which they are the enigmatic rests. There is something chirurgical in these fragments, that doesn’t only derive, in the case of Van der Keuken, from his past as a photographer but also from his position, or rather his posture, as cameraman, man-with-camera or man-as-camera: the eye riveted on the peephole of a camera that is too heavy, the eye that sees and chooses at the same time, that is to say: cuts, slices, clean as a laser. There is an extreme, tyrannical attention for all that frames, and the lived sentiment, undoubtedly nauseating, of an excessive frame, everywhere, always, which implies that there is nothing left to overframe, reframe, deframe. And that which constitutes the frame, of course, is first of all that: the frame that isolates it from the rest, that directs the rest to the limbs of the out-of-frame. Furthermore, it’s the fragment that fixes our look, appropriates it and, in turn, looks at us. Cut off from everything, the fragment of cinema gives us the eye.

When we say that the fragment makes us loose the whole – the whole constituted by “all that remains” – it concerns equally the rest of the world, the rest of the images of the world, the indefinite rest of all that could have been in the same place. The fragment is also that what the professional documentarist has to avoid at all costs – he who has as a mission to make us forget the arbitrariness in the choice of images. The paradox of JVdK who, if he ever becomes well known, will be certainly classified as “documentarist”, is that he makes films against himself, like swimming against the tide, against that part of himself that is content with the easy beauty of images. VdK has made his cinema into a strange machine to de-confound, un-startle, a war machine against the enigma of halted movement, against photography. Not by “denouncing” the illusive seduction of images, but rather by way of excess (at which point the plastic sumptuousness of his most recent film, De Platte Jungle, has something discouraging or even excessive). And the only way he has been able to set up this machine is by making us witness and accomplice of this imaginary operation (the mining, the grafting) that breaks the image into fragments.

The fragment is affected by two possible futures: fetishistic and dialectical. Either it’s self-sufficient, makes us forget about the rest, confounds and startles. Or it stands as a moment in a process, a link in a chain, articulation to what is not itself but that which works with it (what for? For sense, always to come, having the last word, never outspoken). But the opposition only appears to be settled. Or rather: it only meets, with a maximum of acuteness, in the work of filmmakers who are the mystics of real inscription, who besides JMS and JLG we should also include JVdk. It’s in their work that the oscillation between the two futures of the fragment is experienced with the greatest violence – and seriousness. At times the petrification of time in an image, fetish that opens up to (perverse) pleasure, at times the stages, the phases, the inbetween, the dialectics that covers up the desire. It’s in their work (and in Eisenstein’s of course) that we see best at which point, in cinema, the willingness of dialectics has always something to do with the exorcism of the fetish.

Don’t we call dialectics this craft, for filmmakers, that consists of not ceasing to retrace their steps, towards their own productions, their images, to feign to find them changed, become “other” (changed by the look of the spectator – this rival), and giving themselves the right to go back, “covered up by dialectics”. Refusal to abandon them, refusal to manipulate them, shame to the spectator for seeing them wrong, duty to do something about it, it’s one single operation, but in multiple times, comparable to the act of the painter who “takes distance” from his canvas, to see it in another way (detached, as if it was made by somebody else), before the silent order to go back to it is suggested (and, between two strokes, the word of order is precisely: don’t touch!). That is how one can turn his productions into objects of his thinking, this is how the two futures of the fragment come together, in this detour which is going and returning at the same time*. I’m thinking of Godard having the “obligation” to go back to certain moments in his film (Victoire becoming Ici et Ailleurs), like going back to the scene of the crime, or Straub-Huillet filming a book that they’ve read and filming the author of that book reading today what he has written yesterday. Or Van der Keuken remaking Blind Kind.

There is an expression that summarizes well the cinema of VdK, form as well as content: unequal exchange. It indicates a political reality which is the last word of the relations between the rich and poor countries as well as the status of all cinematographic fragments. Every fragment is seized (at the same time victory, extortion and mining) from something, cruelly, arbitrary. The unequal exchange constitutes the fragment but in return the fragment makes us forget about the unequal exchange and tends to play fetish. The unequal exchange finds its way about in the situation of filming (extortion of over-imaging) as well as in the choice of places or framings. It’s through this omnipresent dimension of unequal exchange that the moralization of the relation between film and spectator is brought about (the possibility that a film is abject). One could go on to say that every fragment (all that results from a decision, a choice, a toss of the dice) is injust.

And this unequal exchange, if it can’t be abolished (it is inescapable), at least it has to be made present, it has to mark the images and make the spectator responsible. “Every scene”, writes Fargier (Cahiers 289), “even before being incorporated in a sequence, sees itself already being stratified during the shooting by the telling collision of the real and a look.” Since about fifteen years, the films of VdK (that’s where their political dimension lies) don’t stop proclaiming that every exchange is unequal.

Unequal exchange (1): filming/filmed. Only in the act of filming manifest itself the impossible reciprocity between the one who films and the one who is filmed, which VdK illustrates, in the most radical way, by making infirmity one of his favorite themes. Facing the blind (in Herman Slobbe, see also the text by Fargier), the deaf (in De Nieuwe Ijstijd the Dutch workers are deafened by the factory work), the ones who do not dispose of vital space (in Vier Muren, small film about the housing crisis, the impossibility of holding up – see Cahiers 289, “Espaces contraignants”), facing all these limitations of perception, there can be no “good place” for the filmmaker. The unequal exhange, if I dare say so, stares you in the face.

It’s here that VdK commits himself, risks something. He doesn’t turn himself away from these boundary situations (that he visibly holds dear), no more than he enwraps them in the abjection of a discourse of assistance due to the most “disadvantaged”. He pushes the search for the “wrong place” as far as he can. And if the good place, in cinema, is where we forget our bodies, the wrong place, the one of the moralist, is where the body reminds us of ourselves. In order to better bring forward the inescapable character of the unequal exchange, one has to draw out the two poles of exchange, that is to say: one has to bring forward the body of the filmmaker. I refer to the words of VdK, which show evidence of lucidity with regard to what he does: “The camera is heavy… It’s a weight that matters and entails that the movements of the machine can’t take place freely, every movement counts, weighs…”. We are spectators twice. We cannot have a just relation to those who are filmed (all infirmed in one way or another, because they are being filmed) than from the moment where we also have a relation with the pain, the work, the shame (physical and moral) of the filmmaker.

The moral of a filmmaker is always the search for a triangulation: filmer/filmed/spectator. It is always, in the way that it implies a posture of the filmmaker (or an exhibition, a pose), indissociable from a dimension of scandal. The identification of Van der Keuken with Herman Slobbe is scandalous (the exchange is too unequal) because it is scandalous that the difficulties of the filmmaker’s work echo the existential difficulties of a young blind man. In the same way that it is scandalous that Godard tries to make a young welder understand that the gestures of his craft are also the gestures of writing, writing being the craft of Godard (Six fois deux: nobody here). But these scandals are precious. Because it’s on this condition (bringing forward the filmmaker’s body) that Blind Kind sends back to oblivion all that it could have been (humanitary docucu to shameful voyeurism) and ends up giving us access to the character of Herman Slobbe, as he also exists outside of the film, with his own projects, his callousness, and most of all – that’s where the biggest scandal lies – his relation to pleasure. The film ends with a strange “each one for himself” that doesn’t make sense except for the fact that, for twenty minutes in the film, everyone has been (everything for) the other in regards to the spectator.

Inequal Exchange (2): here/elsewhere. Why would there be cinematographic fragments, if there are people for whom there is nothing to see or hear? This question, we just saw, allowed to highlight, almost ad absurdum, the unequal exchange between filming and being filmed, and all of the sudden, the arbitrariness of all fragments. There are other questions, also present in the films of VdK, that have more to do with his ideological and political choices and his rigorous anti-imperialism. Why film here, in this country, if the key of what we are filming is elsewhere, in another country, situated at the antipodes? In the three films that he has devoted to the relations between rich countries and poor countries (the North/South triptych), VdK doesn’t deal with the “good place” as much as he takes infirmity as subject. All the more so because he knows that the exhange between rich countries and poor countries is more and more unequal. It’s a similar reality – imperialism – that all at once yields one people dependant of another, chains them (pillaging, unequal share of the crumbs of pillage) and exotisizes them more and more (folklorisation). It’s also imperialism that allows the filmmaker to interweave diverse fragments: an icecream factory in Holland, a shanty town held by leftists in Peru, a supermarket in the States, fishermen in the Balearic Islands etc.

This game of here and elsewhere subsists even though the third-worldly sensibility (and rhetorics) of the seventies gives way to a certain disenchantment. At the moment of the war between Vietnam and Cambodja or the Marrocan intervention in Shaba, it’s first of all in Europa (Voorjaar), and then where he lives, in Holland (De Platte Jungle), that VdK pursues the dialectics of here and elsewhere. In this shrinkage of political horizon, this passage from macro to micro, it’s always the same search for chainings that moves the filmmaker, who nourishes his coming and going between fetish (the link making us forget about the chain) and dialectics (chain that doesn’t want to know about links).

What accomplishes itself is a ecological sensibility, already present in the triptych and what is without a doubt – for Van der Keuken as for all the moralists of real inscription – the only way to save politics. Which is to say: follow other chains than the chains of economic exploitation, follow the thread that binds the animalcules of the Waddenzee to the workers at sea and the ones in the nuclear power stations. There is, in this dialectics of nature, a politisation of the idea of environment which in return permits to get across the line between here and elsewhere, not only between the continents, but also between things that are infinitly closer, in the same place, at the most in the same scene.

Unequal exchange (3): this/that. It’s the third operation, which consists of marking the arbitrariness of the fragment in the act of filming (it is therefor essential that VdK is his own cameraman). It consists of displacing the attention towards the edges of the frame and towards the immediate out-of-frame. “When I shoot I sometimes try to look a bit towards the left or the right, and when there is something very insignificant or too significant introducing itself, then I go back.” In this strange practice of deframing, it is as if the fragment doubles itself before our very eyes, unhitching from itself, producing the time for hesitation, in a sort of oscillation, the cruel arbitrariness of the cut by the same glimpse that excludes (beyond the edge, the outer-edge). Practicising a right to look, certainly, but of a very particular kind. Because what is produced in this movement of going and returning, is not a dramatisation of the out-of-frame as a supposed reserve of what threatens or boggles the frame, but what Bonitzer calls (in his text about deframing, Cahiers 284) a “suspens non narratif”. Its function is rather to insinuate a doubt, a distrust in regards to the legitimacy of the frame (filming this… but this, next to it, might also be good…). The fragment dramatizes itself, detaches from itself, in order to signify what is a toss of the dice (arbitrary, happenstance) but also a stroke of force.

In the last analysis however, VdK’s struggle to dialectisize the fragment (we have successively seen an intersubjective dialectics, a dialectics of history, a dialectics of edge and outer-edge) stumbles over the irreducibility of the fragment. Of the fragment of cinema, this fetish. Writing about Nietzsche, about ”la parole de fragment”, Blanchot writes: “A speech that is unique, solitary, fragmented, but, by virtue of being a fragment, already complete in the breaking up from which it proceeds and of a sharpness of edge that refers back to no shattered thing.” It is not coincidental that Blanchot signals the sharpness of the fragment, adding at once that it doesn’t refer to any shattered thing. Nor any enlightened thing. Because the shatter leads us towards the light. Writing about the fetish, Rosolato (in Unknown Binding) signals: “the dullest, dirtiest objects always have this ability, proven in a way that is much more blatant than it imposes itself, a contrario, for a glowing that only exists because of the sole attraction that is conferred to them by way of their role as fetish.” And thereby, the light, the dissemination of luminous sources and points in VdK’s work originates in a sort of intimate illumination. The list of points, rounds, luminous circles would be long. Jewels or shiny filth. From the shimmer of a turning door (Vier Muren) to a piece of bloody meat. Eyes built into a wall or onlooking pebbles (Lucebert); Empty orbits of blind children (first version), redoubled from an opening of the diaphragm, to innumerable television stations, lit up or put out. This light, this materialization of a point of view is not the result of an illumination, but of a grafting. A grafting, an implant of light in the fragment. A quick scene in De Tijdsgeest shows a newspaper announcing the successful implant of a baboon’s cornea in South-Africa. The newspaper cutting has itself the shape of an eye. It’s this grafted light that outlines the empty place of the eye, sometimes literary, that also makes the fragment into a fetish, that is to say: an impossible object in which we can gaze at ourselves.

* It can only be a matter of coming-and-going. Absorbing ourselves in the fetish is, à la limite, impossible (it would be like flirting with one’s own images, like Wenders). Adjourning sense ad infinitum in the name of dialectics is, to say it in a vulgar way, “reculer pour mieux sauter”. In Straub/Huilet’s Fortini/Cani, for example, the retroactive game of signifying blocs, the interrelation of all the fragments, the difference of the last word doesn’t prevent the film from closing itself with one of the marxist fetish phrases (the one where it is a matter of concrete analysis of a concrete situation).

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Translated by Stoffel Debuysere (Please contact me if you can improve the translation)

In the context of the research project “Figures of Dissent (Cinema of Politics, Politics of Cinema)”

KASK / School of Arts

translator’s notes

(1) The title of this piece is borrowed from James Agee and Walker Evans’ Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941):

“For in the immediate world, everything is to be discerned, for him who can discern it, and centrally and simply, without a either dissection into science or digression into art, but with the whole of consciousness, seeking to perceive it as it stands: so that the aspect of a street in sunlight can roar in the heart of itself as a symphony, perhaps as no symphony can: and all of consciousness is shifted from the imagined, the revisive, to the effort to perceive simply the cruel radiance of what is.

That is why the camera seems to me, next to unassisted and weaponless consciousness, the central instrument of our time; and is why in turn I feel such rage at its misuse: which has spread so nearly universal a corruption of sight that I know of less than a dozen alive whose eyes I can trust even so much as my own.”

(2) JMS = Jean-Marie Straub. JLG =Jean-Luc Godard