By Masao Adachi

Written in 2002. French version published in ‘Le Bus de la révolution passera bientôt près de chez toi’, edited by Nicole Brenez and Go Hirasawa (Editions Rouge Profond, 2012)

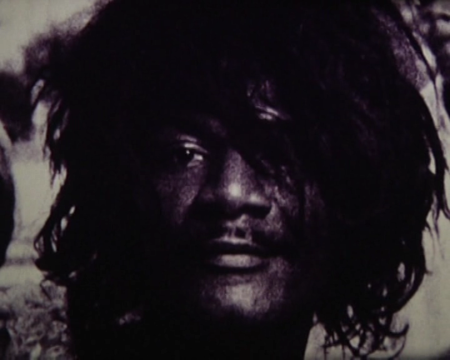

1. About the black screen, once more

To be honest, until I watched Ici et Ailleurs (Here and Elsewhere), my memory of Godard’s cinema was merged in my head with all the other films of the Nouvelle Vague. They were mixed up in a blurry silhouette that seemed to erupt from a magic lantern. But then again, for those who know Godard’s films, this blur of memories isn’t all that surprising.

And yet. While watching Ici et Ailleurs, my vague memories were going in all directions, and every image, every sound was mutating into a tidal wave, sweeping me away from all sides. Was I really watching Ici et Ailleurs, or was it my memory, in which I had buried all those memories and those intimacies, which was forced to open itself like an old book of magic spells with stuck-together pages? I was in the grip of a great confusion.

Suddenly, in the middle of this wave of sounds and images, I could not help noticing once more that my memories of Godard and his group were above all tied to their force as militants, their capacity to evoke the agonies of their contemporaries. Ici et Ailleurs manifests a spirit that we shared with comrades all over the world, mobilized as we were by the march towards the creation of a new world. The film recounts the shadows of the historical time and space as we lived it back then. It is an account that demonstrates the painful road travelled by those who marched without halt in the middle of those shadows, towards a confiscated goal.

It is often said that Godard continued on this road with several other films, but it is above all in Ici et Ailleurs that he tried, through his own desperation, to narrate the problems of a whole era. In his inability to let himself whither away because of this desperation, he has left us this ultimate letter, addressed to all those who will survive him, a sort of “testament”. Twenty-seven years after being made, not a single word has aged. On the contrary, I think that these are words that resonate in the most lively way possible in today’s world, in 2002. They reflect the effervescence of agitators who were very much alive in the spirit of the time. In addition, the sorrow and the irritation of a Godard who was constantly in search of a new life force for cinema has reminded me of this era, and the zeal that emerged from it.

I have also made a decisive discovery in Ici et Ailleurs.

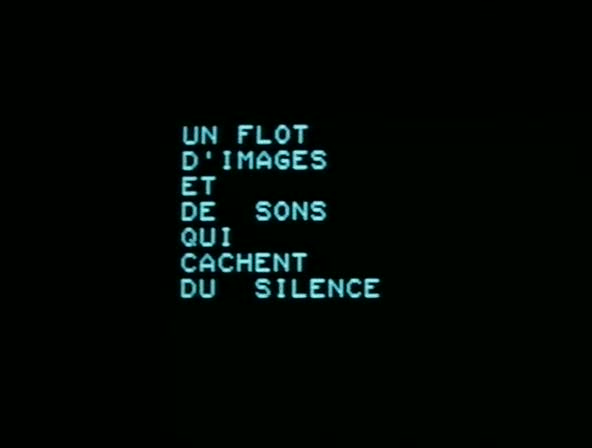

Godard’s group, in the late 1960s and early 1970s, used the method of the tableau noir, or “black screen”, in a perfect example of this cinematographic language that he and others developed, and which as he said, proposed to “make possible the realization of our images and sounds, our cinema”. In other words, they wanted to express a message by way of silence. At that time, I criticized that method, wondering if it wasn’t simply some sort of flight towards aphasia. But this time, while watching this black screen, I told myself that Godard was giving us an alarm call, warning us of danger, a trap: “We are being seen so we don’t see anything.” I was unable to sense this other message at the time, this despair of an era during which Godard, with such dedication, explored ways to make himself understood by all.

I might be reproached for repeating the same things over and over again, but I really want to write Godard about this profound and new emotion that I felt while watching Ici et Ailleurs.

2. The possibilities of the struggle for the liberation of Palestine

There are several points that link Godard and myself. The most obvious concerns our common commitment to the struggle for the liberation of Palestine. Let us think, from our point of view, about what Godard and his friends were able to consider as possibilities to explore, and what has, in contrast, disappointed them, and then compare their positions with the actions and analyses that my comrades and myself conducted at the time. In other words, it is about asking, in the light of this commitment to the liberation of Palestine, of what this “despair of an era” contained in the black screen wants to tell us. We have to clarify the message that Godard tries to communicate, and the reasons that have pushed him to change the title from Jusqu’à la Victoire (Until Victory) to Ici et Ailleurs.

We can already discern an answer in the process of self-transformation undertaken by Godard and his comrades. They indeed clearly adapted themselves to the characteristics of the process of development of the struggle for the liberation of Palestine.

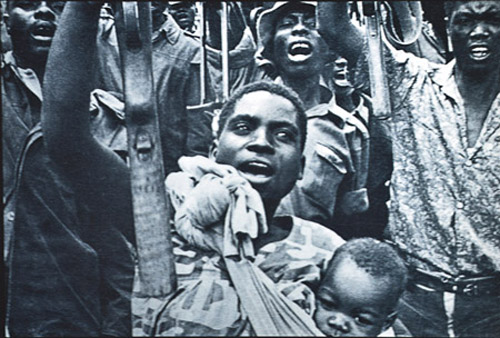

After 1968, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) assumed the role of leadership of an ethnic movement. It passed from a political and peaceful activity to armed struggle. The PLO defined this “strategic defensive war” as the last stage of the resistance, and reinforced offensive armies against the Israeli occupier. When Godard travelled to Palestine in 1970, the organization was at the height of its activities and the Palestinians finally began to acquire an identity on an international level. The PLO imposed itself as the principal representative of the Palestinians. It is important to point out that the 1,500,000 refugees, who had been rejected by the bordering Arab countries, who lived in misery and suffering and were asking for the liberation of their homeland, had become the principal actors in the struggle, and that it was because of them that the “Palestinian government in exile” was formed. Since then, the forces of the Palestinian liberation have led numerous military operations across the occupied territories.

It was in this context that Godard, in collaboration with the PLO, decided to realize a documentary film about the reality of the struggle. Godard declared his position at the beginning of Ici et Ailleurs: “From February till July 1970, ‘we’ – ‘I’, ‘you’, ‘she’, ‘he’, go to the Middle-East, to the Palestinians, to make a film. And we have filmed things in this order and we have organised the film that way… saying: here is what was new in the Middle East. Five images and five sounds that had not been heard or seen on Arab soil. The people’s will + the armed struggle = the people’s war + the political work = the people’s education + the people’s logic = the popular war extended, until the victory of the Palestinian people.”

To summarize, Godard here evokes the road of a war of the people. He declares his support for the armed struggle of the PLO, acknowledging that the liberation of Palestine had not been possible in a peaceful manner and that the Palestinians had no other choice than to engage in a long popular war against Israel, with an army in which equality between man and woman was considered necessary. Those were the principal themes, and they were as important for Godard as for the PLO. In substance, the method taken up by Godard can be summarized as follows: to use sound and image to paint a frontal portrait of the people in revolution.

When Godard was getting ready to finish the film, Black September happened, the month in which there was a real massacre of Palestinian fighters. At that time, Israel was not the only one fearing the victory of the Palestinians. Various Arab countries also thought there was a risk that too great an influence of the Palestinian conscience in their respective countries could take down their own regimes. Then the government of Jordan found itself confronted with such nationalist slogans as “Let us transform Amman into Hanoi!”, launched by the Palestinians. Fearing a coup d’état, it in turn started to engage in its own oppression of the Palestinian forces.

The violence of the coup inflicted on Palestine during this event certainly gave Godard’s group food for thought. Numerous collaborators were killed and the production of the film found itself in crisis. And that is not all. The extremely abrupt change of the conditions in which the Palestinian forces found themselves must have led Godard to completely rethink the form of the coproduction. The filmmaker was obliged to look for new possibilities to continue to work with the PLO.

We cannot exclude the idea that in order to revive the production of Jusqu’à la victoire, the group was considering taking up the events of Black September in the film. The importance of this drama demanded a reworking of the strategy for the liberation of the Palestinians. Meanwhile, the PLO evidently did not want to increase its hostility towards the Jordanian government or worsen the antagonisms at the heart of the Arab population, already brought to light during Black September. The PLO could not go along with Godard’s proposition, as it advocated a reinforcement of the nationalist movement and the popular war to resolve the internal conflicts within the whole of the Arab countries.

This information was given to us soon after we arrived in Palestine ourselves, where we were confronted with the same problem. So it seems to have been political issues that prevented the production of Jusqu’à la victoire from being finished.

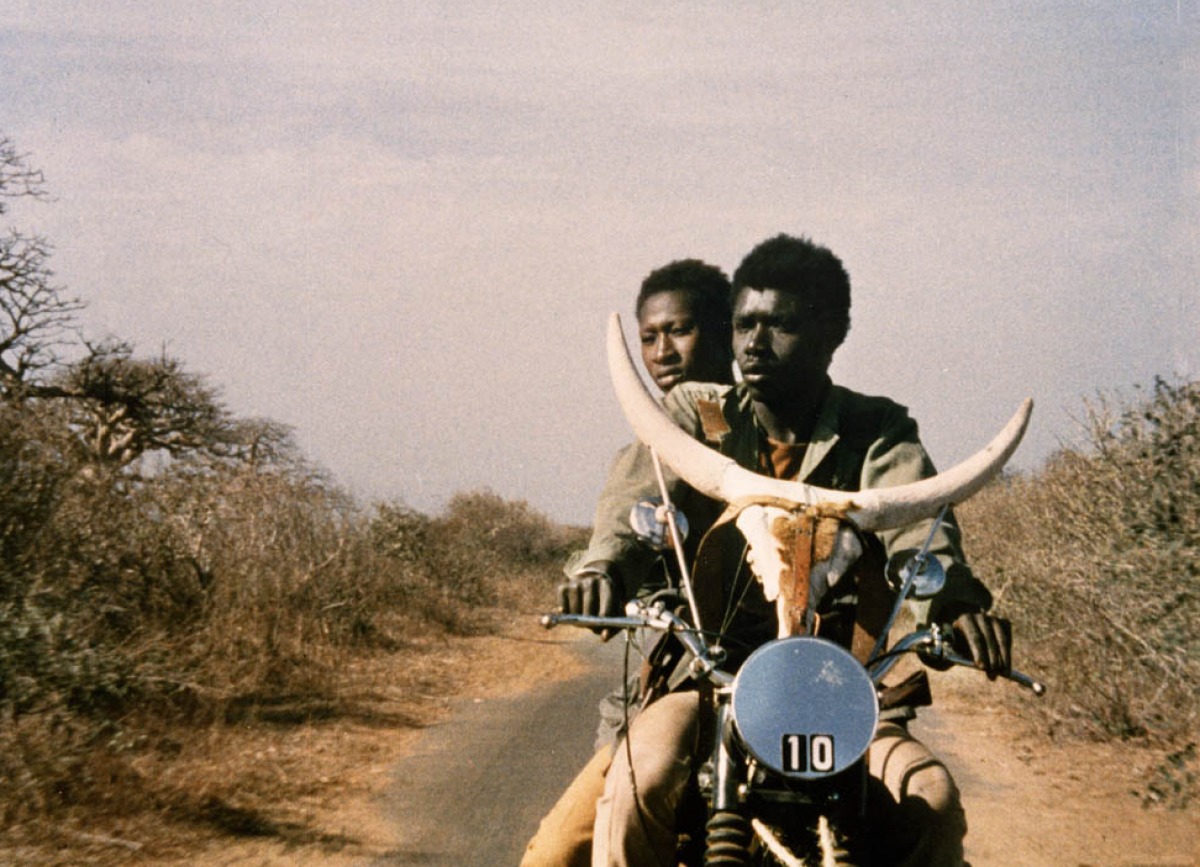

3. Significant differences despite commonalities

In 1971, we started the production of a documentary film depicting the conditions of struggle for the liberation of Palestine, somewhat similar to what Godard’s team were doing. Then we had to face yet a new tragedy for the Palestinian camp: the battle of Jarash. (1) The royal Jordanian army, together with the Israeli army, launched a menacing attack, wiping out a whole Palestinian battalion on the mountains of Jordan, which was an outpost for the offensive against the territories occupied by Israel. In the middle of shooting the film, we witnessed the determination of the Palestinian forces who, far from willing to retreat, either militarily or politically, persisted on the road of armed struggle. Our film, Sekigun-PFLP: Sekai Senso Sengen (The Red Army / PFLP: Declaration of World War), reflects this situation. Realized in collaboration with the FPLP, it is a document that we later showed in Japan, as well as in certain Palestinian camps and in Europe.

Our engagement with Palestine consisted above all in experimenting with militant cinema in the context of the struggle for the liberation of Palestine, while at the same time supporting the struggle in Japan, in order to create a global solidarity in favour of armed struggle.

Fundamentally, Godard’s engagement had the same starting point as our own. We had in common a position and a will to change the old system that dominated the era in which we were living. That is what led us to voice our support for the transformation of the struggle in popular war, by and for the people. But the shift in the politics of the PLO created a gap between our points of view, and it eventually imposed a change of method in our respective cinematic approaches. Godard and I have each drawn our own conclusions, and these have led to different responses.

At the start, we shared with Godard a desire to experiment with the new possibilities of cinema. The events, however, led us to reconsider the fundamental question of our way of working on the resolution of the problems linked with the development of a cinematic activism, starting from zero. This question was crucial. We had to include in the global vision a common experience of the research of possibilities of the worldwide revolution, symbolized by the struggle for the liberation of Palestine.

This is why the differences that separate us have given birth to films underlining those differences, despite the proximity of our commitments. It is also about questioning to what extent our films, or rather the similarities and the differences between our approaches to cinematic activism, could be linked to the worldwide revolutionary movement. Our differences are not determined by our vision of the revolution, but rather concern our respective conceptions of the strategy that the movement of worldwide solidarity had to adopt.

This being said, the particularities and the contradictions that distinguish us are well and truly discernable in Ici et Ailleurs and Sekigun-PFLP. At the point when we were working on the production and distribution of our film and when I joined the international forces for Palestine, Godard and his group abandoned their film. After five years of tormented reflection, they decided to rework Jusqu’à la Victoire into Ici et Ailleurs.

It is perhaps not pertinent to compare the results, but as we finished our film and engaged with an activist movement, we couldn’t help wondering why Jusqu’à la Victoire was not completed in collaboration with the PLO and why a hiatus of five years separated this first draft from Ici et Ailleurs. Could Godard and his group have refused to finish the film for uniquely political reasons, because of a difference of opinion with the PLO? Or perhaps the independent financial resources dried up, making the continuation of the shooting impossible? Until I finally watched Ici et Ailleurs, I thought all these reasons were possible.

Today, I don’t think I was completely wrong, but I have to admit that I wasn’t completely right either. Actually, during the period when the production drew to a halt, Godard and his comrades did not question the spatial and temporal void that separated Palestine and France. They had instead given priority to a reflexion on the transformation of existence at the heart of our societies. Later, they reformulated their reflection in regards to their commitment to Palestine, which was failing. They acknowledged the weakness of their subjectivity and integrated this in a new structure that constitutes the principal message of Ici et Ailleurs.

Godard said it himself: “And then we came back home. I came back, you came back. In fact we haven’t recovered yet. We finally came back. She, he, you, I. I came back to France. It wasn’t working out. And then days passed, months passed. It’s not going well anywhere. Nowhere. I can’t do anything. In France, you soon don’t know what to do with the film. Very quickly, as they say, the contradictions explode and you with them.” He rather openly confesses being torn between France and Palestine, suffering after having stopped the production of the film.

This means that the disputes concerning the content of the film and the lack of funding were not the only reasons. What then were the other motives? I think that the filmmakers were asking themselves how to build a bridge to the new stage of the struggle: going beyond their belonging to society, even though they were socially and politically divided.

If this is the case, one has to ask in which way the team and Godard himself proceeded to sublimate their desire, so far away from Palestine. Did they maybe take some distance, during some time, from their involvement with Palestine? In truth, this was not at all the case. In fact, Ici et Ailleurs reveals itself as an experimentation with new methods susceptible of responding to and coping with a new context for the struggle. These are valid not only in regards to the commitment to Palestine. Ici et Ailleurs also constitutes a tipping point, after which Godard began a change in his cinematographic methods.

4. The desire to pass the border again

What stimulated Godard to take up the project again? At what point, while being so far removed from Palestine, did he pick up the abandoned Jusqu’à la Victoire film, to deconstruct it and recompose it in the form of Ici et Ailleurs?

From the remaining material, Godard chose five images and five sounds: “The people’s will + the armed struggle = the people’s war + the political work = the people’s education + the people’s logic = the popular war extended.” He has not been able to alter them. In Ici et Ailleurs, the authors become attached to “elsewhere” (Lebanon, Syria, Jordan). The words of this language, in spite of the events that have struck Palestine, do not change. “Here”, that is to say in France, such words are considered non-existent.

Godard says it himself in the film: “Probably, in attempting to add hope to dreams, we have made adding errors,” “It’s true that we never listened to silence in silence. We wanted to crow victory right away. And what’s more, in their place. If we wanted to make the revolution in their place, it’s maybe because at that time, we didn’t really want to make it where we were, and preferred to make it where we weren’t.”

Godard continually poses the question of knowing what is keeping them at a distance from this “elsewhere”, these scenes of struggle in the Arab and Palestinian liberation, in which he and his team had invested in the past. The films from the US and the Soviet Union were what plundered the images and sounds. It is capitalism that seizes the time of life and relations between humans. It is Godard and his friends themselves who are alienated and buried “here”, under the numerous “zeros”, the coefficient of capitalism in France.

Godard and his friends wanted, once again, to go beyond the “zeros” and once more face the battlefield of Palestine and other places, from “here” to “elsewhere”, from “elsewhere” to “here”. But what pushed them to take this turn? This is only my hypothesis, but I am certain it has to do with what happened during the Olympic Games in Munich in September, 1972. After the massacre of Palestinians during Black September, after the “massacre of Mount Jerash” inflicted on the Palestinian guerrillas, it was during the Olympic Games in Munich, just after the battle of Lydda in May 1972, that members of the Palestinian guerillas broke into the athletes’ village. They occupied the village, taking Israelis hostage in order to demand the release of Palestinian prisoners of war. Television stations interrupted their broadcasts of the games and relentlessly filmed the village where the guerillas barricaded themselves in with the hostages. It was a moment of tension that Godard described as follows: “In Munich, the force of imperialism was exerted through television. Two billion spectators wanted a program.”

While watching these broadcasts, Godard undoubtedly thought of a way to counter the powerful imperialist message of television. If I am able to formulate such a supposition, it is because we had exactly the same experience. In February 1972, when we were in Japan, working on Sekigun-PFLP, the Japanese Red Army had taken hostages and entrenched themselves in a chalet in Asama.(2) This event was baptized the “Battle of Asama”. Television unceasingly turned its cameras on the event. The authorities distilled a message that impelled spectators to expect “the great scene of the arrest of the guerrillas and the liberation of the hostages”. The whole of Japan was nailed to their seats. This message was more powerful than any sound or word.

We can assume that what had awakened Godard and the others, torn between here, Europe, and there, Palestine, and what led them to take up the challenge to make Ici et Ailleurs, may have been the continuous broadcast of “the scene of pitched battle between the Palestinian guerrillas and the special forces” that unfolded in Munich. This hypothesis seems acceptable to me. Godard’s comment in Ici et Ailleurs is extremely radical: “Take advantage of the fact the world is watching to say: ‘show this image from time to time’. If they refuse, take advantage of a worldwide TV audience to say: ‘You refuse to show this image’. At each final, for example. Ok, we’ll kill the hostages and be killed afterwards. And for them as for us, it’s silly to die for an image. And we’re a little scared”

These words, full of bitterness, are spoken as a counterpoint to the moment when we see the group searching for a way to show Jusqu’à la Victoire on television, with the authors carrying out a critical analysis of their own counter-information film: “Looking back, the things that are described in these images are not all that different than those we can see in whatever American or Soviet films.”

What takes place is a singular process of sublimation that allows for a reversal of the field of possibilities. Let us reconsider Godard’s words: : “If we wanted to make the revolution in their place, it’s maybe because at that time, we didn’t really want to make it where we were, and preferred to make it where we weren’t.” Godard thus reconsiders his counter-information film in order to definitively conclude the impossibility of its succeeding.

We can guess the meaning of the other message brought about by the black screen. The black screen of the Godard cinema, combined with another crucial term, the “memory” of the filmmaker, suggests a smothered howl stemming from the author’s soul. The “memory” that transcends time is both a past and a future. It accompanies us towards a conscience of the present. It is most probably in this way that Godard wanted to cross the border between here and elsewhere. It is not about going “forwards” or “backwards”. It is not about being “here” or “elsewhere”. The border depends on the positioning of “forwards=backwards” and “here=elsewhere”. Do Godard and his comrades mean to imply that the equal sign (=) allows for the infinite accumulation of “zeros” that links Soviet and American films?

What is really happening? I try once again to take time for an inner reflection in front of this black screen. I don’t know how much time I will be able to concentrate. I have to say that while hearing the news about Palestine and seeing Ariel Sharon urging the butchers to continue their indiscriminate murder of Palestinians, the interior of my mind already colours whiter and whiter with anger.

Thinking about it, the ultimate, heartbreaking message that Godard has sent us in Ici et Ailleurs does not reside in the black screen, but in a screen made of the purest white.

(1) Referred to as Gaza Camp, Jerash is home to Palestinian refugees who fled the Gaza Strip after the 1967 Arab-Israeli war.

(2) During nine days, the Japanese population could follow live television broadcasts of the spectacular progress of this hostage-taking, which turned popular opinion against the leftist movements.

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Translated by Stoffel Debuysere, with help from Mari Shields (Please contact me if you can improve the translations).

In the context of the research project “Figures of Dissent (Cinema of Politics, Politics of Cinema)”

KASK / School of Arts