Talk with Pedro Costa. 2 February 2013, Brussels. In the context of the DISSENT ! series. Moderated by Stoffel Debuysere.

Some moments are there to be cherished. Moments that brim with a sense of wonder, of affection, of truth. This was one of them. The setting could hardly have been more modest: a small space, some chairs, a table, a screen, and an admixture of people, a few of them talking, all of them listening, wrapped up in that singular moment of tenderness. The proposition at stake: cinema. To be more precise, the cinema of two filmmakers who have crafted one of the most distinctive bodies of work in the history of cinema: Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet. The principal talker is not only an avid admirer, but also a friend, a soulmate, a colleague, who in his own way has shaken up the world of contemporary cinema: Pedro Costa.

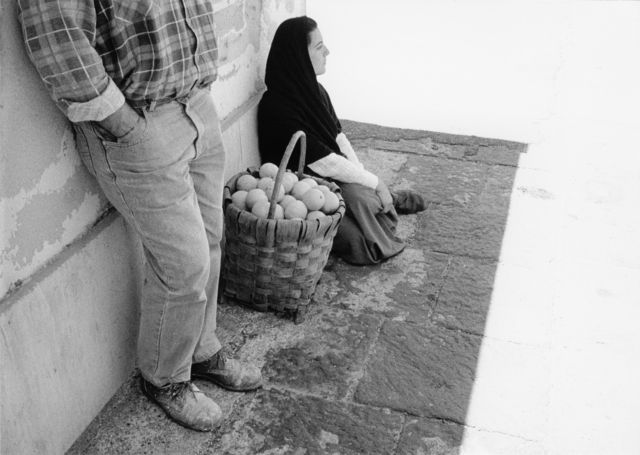

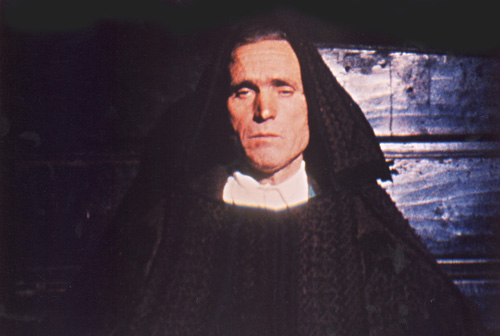

First, a film: Umiliati by Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet.

And a single quote, written by Jean-Marie Straub.

“The spoken text, the words are not more important than the different rhythms and tempi of the actors, and their accents are not more important than their particular voices, caught in the instant, struggling with the noise, the air, the space, the sun and the wind; not more important than their unintentional sighs or any other small surprises of life recorded at the same time, like particular sounds which all of the sudden assume meaning; not more important than the effort, the work done by the actors, and the risk they take, like tightrope walkers or sleepwalkers, going through long fragments of a difficult text; not more important than the frame in which the actors are enclosed; or their movements or positions inside the frame or the background in front of which they find themselves; or the changes and the leaps of light and color; not more important in any case than the cuts, the change of images, the shots.”

Pedro Costa:

For me, every experience of the films of Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet is the same as now, because this doesn’t change. It never changes. It’s difficult to talk about, because this very special film you chose is a very sad one. Especially for me, or for people who are experiencing what we are experiencing in the South, now with these austerity things happening — coming from here, from Brussels, actually. It’s very simple, and nobody does this kind of work today. So this doesn’t change. This kind of work is never done. I discovered that these films existed when I was younger. Now they do not exist anymore, period. And when I saw this for the first time, for me it had this amazing energy and sensuality….

The quote you read seems very concrete to me because I work in this field: I work with cuts, with this kind of rhetoric, so I know the procedure and sometimes I’m afraid. I do not take the risks that he speaks about, but sometimes I’m a little bit afraid. Whenever you do a cut, an infliction or an intonation, whenever you decide something, you have to assume that thing completely. And then I’m afraid. I think everybody’s afraid. More than before, more than yesterday. People do not take that risk anymore. So if we are here to talk about politics and ethics, I think that’s the main issue.

It is as if we are in the position of one of the people in this film, Ventura: “What can I say, what can I do?” Either you are charmed or seduced by something, or you quit and you are left alone. That’s what I feel, I’m really feeling alone. Not because I’m doing something special. Absolutely not. But I’m feeling alone. There’s no more people working in this way. When I was younger this seemed to me a way to make politics… not to make a film, but politics. And it’s the most beautiful thing for me. I was not at all seduced by the idea of making films or charmed by the guys with the guns. That’s not the charm for me, it never was. The charm was to do something as violent, as gentle as everything that Straub says in this way. Against the language of cinema. Because this is not cinema, or rather, this is not the language of cinema.

I never believed in working inside the system. Because this happens outside the system. I Always believed in the outside. It’s a position, and then you have to live with it. But you cannot turn the system around. I don’t believe in that. I’m not that kind of person, I’m not that kind of citizen, I’m not that kind of filmmaker. You cannot work inside the language, you have to invent something else. There are some things in this film, and I’m sure you all know more films by Jean-Marie and Danièle — if you don’t, I hope this one gives you some appetite — there are some things there that you have never seen before in your life, I’m sure of it. The guy knocking on the table: you have never seen this, never in this way. So it’s a way of saying: let’s cut the crap, we are trying to invent, we are trying to work, to search, find another way of pulling something from someone who doesn’t know yet what he is going to do. You have to pull something out that he doesn’t know he is capable of. That is the work, for me, that is the politics. To give appetite to the other one, so that he can go say something to his boss, his friend, his employee, his lover. He can say it in another way, not in the same old language.

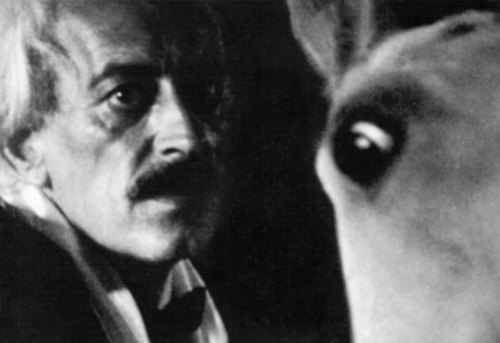

They are the guys who have never let me down. I’m a fanatic. They are fanatics. I think it’s the only way to talk about this kind of work. There is no other way of working in cinema or art. Did you see these mysterious shots of wood? It happens two or three times in the film. It’s very strong. When you do things like that, you’re done for the rest of your life. It’s over. You cannot work in this town anymore. You have no more job in this town, in cinema. It’s going very far. Sometimes if there is no reason to do it, you have to go beyond your fear. I tell you, I cannot do it. It’s not a matter of talent. It’s just that I don’t work that much. It’s that simple, there’s no secret here. It’s not a question of being well practiced in the ways of writing scripts, it’s not the number of films that you have seen… It’s life, it’s taking a risk that has nothing to do with cinema. Because we’re not talking about cinema now.

It’s a tension that is very hard to maintain because it’s not in the films, it’s in life. We all know it’s very difficult to be in love all the time. At least, that’s how I feel. I knew Danièle and I was very close to her, perhaps more than to Jean-Marie, and I know they were in love all the time. I’m not saying that you need to be in love to make art, or to live, to be alive, but it helps. Again, there are things here that you have never seen in your life. It means that they try to keep this tension at the maximum level. It’s very young, very alive, very political, very resilient. All the words you want. But it’s in life, not in cinema. Actually this is one of the least visual of their films, I think. Everything is what it is. Like one of them says, “it’s here, it’s what it is”. So it’s not film, it’s something else. The difficult part is not making the film, it’s believing in the film. It’s believing that this is material, that this is more than material, that we can represent it in another way. The strength to believe in going from saying something to doing something. It’s like Ventura trying to get up. You cannot get up nowadays. He can’t get up, because he was seduced, charmed.

This is a film that has death in it, that’s why it’s a sad film. There’s something very “there”. You die. You die for some things, you die seeing certain films. When you go to films today you don’t die. But you have to die a little sometimes. Me, I died a thousand times. And I was not reborn immediately. Today it’s only ghosts. I’m tired of them. There’s no ghosts here. There’s no tricks. It’s something Jean-Marie always says, “you should never ‘faire le malin’ — play the smartass”. These films never do this. They don’t play the smartass. You choose this or you don’t. I’m also very sad because we didn’t win this. We lost.

There was a film before this one, called Workers Peasants (Operai, contadini, 2001), which is about what happens before. These people tried to reinvent everything: this village, this life, this commune. In this particular film they quarrel, they discuss, they fight, there are some love stories… This is the sad epilogue. It felt so sad today. But it’s so well done. There are no metaphors here. In films, there are usually constantly metaphors for everything, but they are the only artists I know who are beyond metaphor. It’s all crystal clear. It is as sad as — when I think about them in a historical context — the last films by Eisenstein or Vertov, they have the same effect. I see them dying, lying down, giving up, taken down by the forces of progress and power. So it’s a very sad film, but it’s a film that has to be done. It all comes from Italian writers who were very important — Vittorini, Pavese and others. They didn’t give up, but they were forced to stop writing. Pavese ended they way he did, Vittorini cried for the rest of his life. And we, we are still crying.

What they are saying is that they are a bit lost and don’t know their way. That was in the original text and it’s done perfectly: actors, camera, direction, flowers, rivers, things that pass… And ourselves: we are perfect in this film. When I saw From the Clouds to the Resistance (Della Nuba Alla Resistenzai, 1979) when I was younger, I fantasized that the movement in a film was not only there on the screen, but up here, in our head. So the work you have to do is not an intellectual work: if you understand, you understand, If you don’t, go home, wait, grow older or forget, go somewhere else. It’s a balance: you have the movement in your head, as if the camera is your head. For me, the camera was always in our eyes. That’s why I say that these films are the fastest for me, because they make me think so much. This never happens to me with other filmmakers. Sometimes even Godard seems very slow. When I was younger I was a lot into music, and this was for me the exact correspondence to the music I was listening to, which was very noisy rock music, very simple, tense, nervous. Even Godard seems a bit more rhetorical, more stuck inside cinema. Even if he appears to be more revolutionary, more of a genius than this couple — which I do not think — sometimes I thought he was slowing down because of the rhetorics of the language. It’s like poetry: they are poets. You’re stuck if you’re into language. Everybody knows that. At the same time you cannot do poetry with poetic words. You cannot write a poem with poetic terms. You have to escape, work, work a lot.

For me, work is, or at least it was the only thing left for me. I came a bit too late, at a very bad moment. The people I liked and the things I wanted to do were very “underground” — but not in the marginal sense, they were not fancy or elegant or making money: they were really despised. They still are, by the way: recently I tried to help produce a film of Straub, but I didn’t manage. Anyway, at the same time Godard was in that very political moment, so nobody cared about him. Those were the things that inspired me. I was never into the avant-garde or experimental film, I was never seduced by it, I always thought it was too easy. It’s my Capricorn side. When I go to museums and I see those videos, I always say “it’s too easy, let’s work a little bit more and be a bit more provocative.” To go beyond, you have to respect some things. It’s hard to say, to confess, but you have to observe, and not forget things. For me, in experimental cinema, they forgot everything: Chaplin, Griffith, … not the angles or the shots, but the spirit. I’m talking about politics. Experimental cinema pushed for a kind of politics that was not interesting for me. Guy Debord, for example, I was never into. Far from it.

When I started I was confronted with a big dilemma. I worked as an assistant for about ten years. It was a nightmare. I recently read some biography that said “he worked as an assistant and he gathered a lot of un-useful and traumatic experiences”. It was exactly like that. I realised I did not want to work in this kind of thing. But it’s not like I’m going to try to change the industry or the rules. No, I just don’t want to work this way. But it took me three films and a lot of years to really get out. For them, it was a bit easier. I shouldn’t be saying this, but in the 1950s and ’60s, it was somewhat different. Me, I had to spend the 1990’s trying to figure out how to get off this train. I had to find the people, the place, the story, the narrative, the politics, everything, to be able to start again. It’s about production, in the Walter Benjamin sense. It’s the nights you spend thinking about production. The mornings you think about the art mean nothing. Or the nights when you think about the shot, or the girl, or the flower. It’s not like that. It’s a little bit abstract sometimes: it’s money, it’s cars, aspirin, social security, going up a stair, making a phone call, those kind of things that have to do with real fear. Should I call, should I explain, expose, should I go — like in the Clash song? That’s the risk. I think today it’s very difficult and I’m not really sure if the best way is not to work inside the system again. Not for me, but for young people. I’m outside, I’m retired.

I work alone too much, that’s my problem. I would like to work a little bit more with the people I usually work with. Not with technicians because that’s not really possible for me anymore. One thing Godard once said is that you have to have people around you who do the same things, someone at the camera or the sound who are really working with you. I could be here telling you that I have some partners, but I just don’t. It’s not that no-one knows what I’m doing, that it’s a secret or a mystery. It’s just because film has become economically very violent. I can’t find anyone to stay with me every day for six months. It’s not possible in my situation. I really want to make films that compete with Tarantino, I’m not kidding. I will always try, just like Jean-Marie, to put my film in the same place as Tarantino’s: in the cinema, in the multiplex. To make the same kind of objects, tell a story, more or less in a kind of rich way. We want to do the same thing, we want to be judged or appreciated in the same marketplace, even Jean-Marie wants that. But I can’t find people from the industry to work with me. Jean-Marie can’t, because he doesn’t have the money or the patience. I have a bit more patience, I think, but I spend more time. I can still have someone for the sound, because sound people are more sensitive, more here on this planet, as sound is more concrete. But a lot of others I can’t have. They want to be somewhere else, make films in Africa or in Brazil, they need the planes, the cars, the girls, the small talk. It’s the mythology of film and it’s very difficult to fight against that.

When I’m saying I don’t work enough, it’s perhaps because I’m working too much “on the other side”. After my years working as an assistant and doing a lot of terrible things, I thought of only one thing: I have to demonstrate that film can be done in that place – Fontainhas. I have to tell these guys that film was born in this place. And it was so evident, so simple. Just see a film by Chaplin or Griffith: it was born there, in the street corner. So I spent a lot of years trying to explain ”this is a tripod, this is a camera, pointing there. And there’s a guy passing. We can go from here to something else and then there’s the sun and we can invent a scene…” Just telling a lot of people, friends, people that I like, that I wanted to do something with them. But in order to do that I needed them to understand. So I was making a transfer of everything that I knew to that place. We did two or three films that way. But I invested a lot in the production side of things, and perhaps that’s the good side of those films that I made. That they are made there, with those people. Something is felt, something comes from them too.

Everybody has one’s own secret awards, and mine is not the artistic value or compensation. It’s much more the work we did there — a lot of people worked for that. I don’t really like documentaries, I never liked them, but there is a certain documentation in what we did. And now it’s done, and people see it, they think and they reflect. And that has a value. It’s like Jean Rouch’s work: something that has value. It was important. But now it has become something else.

It’s the stupidity of me thinking that film was supposed to record human life. I did that, and now I’m stuck. I’m no place. Because I don’t like documentary — and it’s not that anyway. And I can’t go on recording something that doesn’t exist anymore. Fontainhas doesn’t exist anymore, physically, but most of all the soul is missing: they are broken, as broken as Ventura. So it’s too much for me to pull them back up again. I don’t know how. And now I’m into artistic deliriums, I’m afraid. I talked with Jean-Marie about that: we are doing things to forget, not to remember. First I was doing things to remember, now I ‘m doing things to forget. That’s my feeling. I cannot explain. Every time we get to something like the film you saw recently — Sweet Exorcist — I have the feeling we are doing films to forget a lot of things. Forget the life that went before, forget what we did, perhaps forget to start again. We have to start something new, but what? It has to be done, but I don’t see anything new in films.

I do not have the sets, the houses, the skies, the forest, the sea. They — Straub-Huillet — have taken that away from me. I cannot do a shot of the sea. I can’t. Even if the script says: “and then he looks at the sea”, I will never shoot a sea, I promise you. I don’t even have text to work with anymore. Because they, the people I’m working with, are forgetting. They have so many problems. Do you see what I mean? How do we start from here, alone, everybody alone, if there is no possibility of a collective thing. I don’t see it because I don’t talk with anyone. I don’t want to be in the film-film thing. I can’t. I can’t do a film like Olivier Assayas. I don’t know how. That mythology of film, for me it doesn’t exist. It never existed.

In Umiliati you saw the soldiers, the guys with the red scarfs. They say they come to charm, to seduce. I’m not seduced by that. I was never seduced by cinema. It’s so beautiful I have to tell once again the story of Rossellini. It was Truffaut — he made some nice films but his texts are really wonderful — who was talking about Rossellini, who he knew very well — he was his assistant for a while. He said: “you see, there are people who are not born to make films, Rossellini is one of them. Because he’s not stupid, he’s not an idiot. He hasn’t got the naivety to make a film. Because you have to be a little bit stupid.” When Truffaut says “stupid” I know exactly what he means. Anyone who has tried to be behind the camera knows what it means. Faking, being stupid faking, faking being intelligent, faking a lot of things. Rossellini couldn’t do that, he couldn’t say “and now you kiss each other and you say I love you”. He just couldn’t do that. He did several films like this. And Truffaut said that his work goes from the city of Rome — in Roma, città aperta — to a lot a little cities — in Paisa, a film shot all over Italy, from Sicily to the North — to an Island — Stromboli — and a continent — Europe 51, a very beautiful film. And then he wanted even more. Because he was loosing his beliefs, he was loosing it completely. You can see that in Voyage in Italy: It’s a magnificent film, but he’s completely nuts. You see him going away. And then he literally goes away to India — which is an amazing film. And after India, he goes to the abstract planet of ideas: Socrates, Jesus… He was out of his head, saying things like “TV is the future of democracy” and so on. What is nice about Truffaut is that he said: he was too stupid to be in this business. He never said he was too intelligent, too kind, too gentle. He never said that, but that’s what he meant. This kind of people, like Jean-Marie, are too kind for this world, for this cinema. Too gentle, too intense to make films. So we should say that films should be something else. But what?

I felt it was important for me to look for something new, just for me, privately. Which means a little place on this planet to put my camera, and for that I had to convince the people around me that it was possible. Because they were saying “don’t film this, this is ugly, this is poor, there is nothing to see. If you put a pistol, it will look much better”. My work was to try to convince them that we didn’t need a pistol, or somebody saying “I love you”. It was very difficult, it still is. It’s because of the mythology I was talking about. So when I did this part of the job it was obvious that I had to work with what I had, with what they gave me. One of them told me he wanted to do his text like if he was dying in the hospital. He really wanted to say his text that way. I resisted a bit, already thinking about the email or the fax stating “dear sir, we are doing a film … we want to ask your permission… etc.” I was already dying! I’m very lazy for this kind of thing. That’s the kind of work I don’t want to do. Because I think there are great things in not doing this work. If you don’t do it, it’s resistance. Even more so because you have to pay if you want to shoot in a hospital or a museum. For example, I wanted to film a painting in an art museum. They asked for 300 euro, I said “no, I won’t do it”. So I bought a book — from Taschen — and with a friend I cut out the thing and it’s exactly the same. They will see it, of course. I’ll probably put “museum” just to annoy them, but I won’t pay. Because it’s never used for the right purposes, it’s going into somebody’s pocket. To come back to the hospital scene: the guy had this idea to shoot the scene in a certain way — you never get this from professional actors or technicians — putting the bed in a certain position, putting something under the mattress so that he was bending a bit and so on. The shot is there, everything is white and there’s a big window with white violent light. And it’s a hospital. That’s what we’re doing now, trying to do something between extreme laziness and getting the things that are there.

Of course it’s more complicated than this, there is always some kind of fight. Of course they want to go to the real place. It’s part of our job to resist the institutions, in this case a hospital, or the government, the police. But it’s not that, It’s more about making them think about another kind of language. That’s what I want. It’s not a language, it should be something else. The experience should come from this kind of experience. This worked because he wanted to say something to his mother, it’s part of a very long process. This boy was in bad shape, because of drugs and so on. And me, I make films, I make something that people see and believe. So he took me as a postman to post a letter to his mother. “I’m going there to tell something to the mother. You will help me say that, you will put me in the right position. The best way for me to tell my mother some things: she didn’t help me”, “I’m dying. It’s your fault…” Very difficult things. This art direction comes from there, from a much more violent and difficult place. It always comes from a very serious thing. It’s not about faking, imitating or fantasizing. He believes in this, I don’t and when we get together, it works because he believes. That’s why I work with this kind of people behind and in front of the camera, because professionals do not believe. It’s always technological, technical, artistic. It’s never political.

I do not know anyone in this room who has seen more films by Andy Warhol than me, I mean completely. I challenge anyone. I always liked him, I really like the filmmaker, even more than Jean-Marie. He’s my kind of guy, as serious as Rocky, as strong, stubborn, as mellow as Straub. When he makes you cry, he makes you cry. I’ve seen Warhol’s films in film theatres, and I’ve been waiting in cues to buy a ticket and 10, 20 minutes after the film starts, everybody goes away, just like for a Straub film. And I stay alone with two or three guys, one of them sleeping… In the same way that when you say “Straub”, everybody goes away, screaming “marxist, terrorist, boring!” In the case of Warhol they say: “Rock ‘n’ Roll!”. Nobody has the patience to really see. They see a picture, something from a catalogue from a museum. They never see the complete film. Like they have never seen this film and sometimes they have never seen a Charlie Chaplin film. It’s that simple.

I made a film called In Vanda’s Room. I was suffering to make this film, thinking, dying, I really worked a lot on this film, editing for two years. The suffering was very material. Two or three years after the film was made someone asked me, “have you ever seen Warhol’s Beauty 2?”. When I finally saw it, I had the feeling that he did it just like that .. “let’s make a film”… he did and it was exactly the same as my film. So it took me two years, it took him in real time about one hour. It’s a beautiful film, it has the same thing that I tried to do. I keep seeing the film again and again. It’s a dilemma. I killed myself to do this and he doesn’t give a shit and he does it. He doesn’t give a shit, but he’s a great filmmaker. The core of what I and him wanted to do is the same. What he says is on the bed everything is sexy, even peeling a potato. I write 50 pages about my film. That’s the difference. Sometimes you have to go to the basic simple thing. There’s more examples, but you have to see it, experience it. First you have to see the film. I am convinced there is a cloud of fog and dust surrounding a lot of film art aspects.

I met Antonio Reis when he was a teacher at film school. I went to this school because of him. He made me stay because at that time I was more into music. It was a difficult moment in those years. It was the moment of Straub of Godard and there was nothing more exiting than that. There were a lot of things coming from Europe: this kind of poetic cinema from Budapest or elsewhere, the kind that still exists today: guys with raincoats in places where it rains all the time. And I hate that. But it’s also in music: I was into the Sex Pistols and my friends were into Joy Division. You have to choose. And at that moment film was like Joy Division. Very profound and artistic and philosophical. I’m joking of course, but I’m trying to define something that was awful for me. Everything that I didn’t want was there in that school, and this guy was the only one that saved me, pulling me through. Because I was only saying this kind of bullshit “I hate this and that.” I was just against. And he said “keep saying that, one day you will be tired of it and you will do something.” And I had to do something one day.

Antonio Reis was very important, also because he was the only one in my country who gave me hope. More than hope: he showed that it was possible to make a film in the Portuguese language. For me, films come a little bit from when I hear the words, what people say, the tone, how they pronounce. I hear a lot of things in films. I wouldn’t say “class”, but money. I hear how much they were paid: I see a film and the girl says “I love you” and I say “oh, 200 euro”. I know how much it costs. I’m joking, but there’s a segment in the film I made with Jean-Marie and Danièle in which they speak a little bit about this problem. Which is why sometimes when you work with non-professional actors — people who have other jobs in life and come to do this job as an extra thing — you get more, you get an accent. Accent is always a good thing. You get an imperfection, you get something less to get something more. And you fight with your imperfections. It’s like the guy in the hospital: “I don’t have to be in the hospital to tell you this. So I’m even more intense. See, I’m completely naked”. What you get is this naked rawness. It’s difficult to have this with an actor. I prefer this kind of surprises or accidents. I’m always challenged, amazed, surprised. It’s a life I want, a life of surprise.

I would like my films to be shown as much as possible. Why not in a museum, a gallery, a video on the wall? It’s all the same audience for me. When I started to make films as I’m doing them now I really wanted to have an audience. Now the people I work with are the audience. Each time I make a film, if it doesn’t come out on DVD, I have to make 5000 copies. This abstract neighbourhood I’m always talking about exists. The houses are not there anymore, but the people exist. Some died, some are no longer there, but they have sons and cousins. Again it’s this fascination for film: “I want to see my cousin, my dad’s house, …” So we make a film and we show it among ourselves. Some colleagues… I don’t know if they want this kind of thing. They are content doing the film and showing it in Rotterdam or Berlin. At that moment, ten-fifteen years ago, I needed this response. It felt incomplete if I was doing that kind of work to stop there. Now it’s even more difficult because there are no more theatres in that place there. No more neighbourhood, no more film theatres. When we showed the films there’s was still a theatre. It’s been torn down, it’s a supermarket now. Like I told you, I lost.

Jean-Marie and perhaps Godard — I don’t know him, with Jean-Marie and Danièle there’s also the sentimental thing — I think they belong to an age, time, moment when this kind of work was for you and me. It was for a lot of people at the same time. It could be philosophy or poetry for all young boys and girls. Me, I cannot go beyond “the one”. I can only attract one sad boy. Yes, There’s quite a few of us here, but we’re not a lot. If we pick up some sticks and fight, we will loose. Back then filmmaking and film experience still had some fascination, this kind of mystery that it always had: this emotion, this secret emotion just for you, when you see something and you think “this is made just for me”. People shared the same secret. Everybody thought “this is mine”, but actually it belonged to everybody. Me, I cannot belong to everybody, although I wanted to. Tarantino apparently manages to be shared.

This kind of work — I’m not talking about commercial success, not even critical success — is not there anymore. It’s not the same world. That’s my experience, from my mother and father and grandfather and what they told me and what I saw when I was young. The films I experience now, I feel the difference. Yesterday somebody asked me “how is your workflow?” Workflow today means: the film you’re doing. Just the word makes everything different: “flow”. In my time it didn’t flow, it just stopped. Today the work flows. Workflow today means you shoot something and you go to the end and you show it on DCP. It’s the movement you make from the moment you say “action” to the moment you see it on the screen. No more shooting or editing. Something specific is lost. There’s no more shots, the work or the intensity you have to put in something to be a part of you. It’s no more. It’s something else.

There is a part of work in film that is gone, because of the workflow: the part “flow” is fake, the part “work” is fake. When I go to a lab today it’s completely phony: to change the shot, it takes you ten seconds. It’s not the speed, there’s just no work. The guys working in the labs are not working, but just pushing buttons. Again, they have a language inside them, a digital language in their brains, their hands, their eyes. I’m afraid in their hearts, already, and that blinds them a bit from what I’m trying to tell them. So what I’m trying to say is that there’s not enough work in the films that I see. There are films here and there, the problem is that they’re not seen. Never in the theatre. I’m afraid of things getting exactly the same. If you see a Thai film, all of them are exactly the same, they’re all about ghosts in the jungle. If you see a Portuguese film, they’re all the same. Everything is becoming the same.

This kind of work, the kind that stops: it puts obstacles in front of me every time. But with these obstacles, you jump or you don’t. If you don’t, just go away. There are some films that I admire, but I don’t jump. This kind of work that I like is very useful. Jean-Marie and Daniele never liked it when we talked like this, but I think it’s very useful. Like I think Jean Rouch was very useful. There are no more works like Jean Rouch being made in the world today. No more. Perhaps on TV, but how can you see that when there are 100.000 channels? Somebody has to tell me where. If someone goes somewhere with a camera it’s always for a different purpose. I’ve seen that so many times with young people nowadays, they take their small camera, go to a small island or a desert and they come back with a desert. That’s what I’m pessimistic about. This workflow, this language. The battle that is won is saying that cinema is a language. I fought against that a little bit. Not enough. The Straubs have fought a lot, Godard fought a lot, Rouch fought a lot. It was supposed to become something else than a language. Breaking the grammar. But again: I don’t believe in working inside the language. I don’t even know if it’s possible anymore not to. I think it was, this film we have seen is the proof. Even today some other filmmakers, very few, prove that it’s possible sometimes. But it’s not possible to be seen. I don’t see how I can make a film and go to a theatre and people will come and pay a ticket to see it. No one will come. I know there’s the Internet, streaming, downloading, I get a lot of things from different places, but it’s a different kind of work… perhaps it will make me change something again. I don’t know.

Actually, this digital revolution saved me a little bit. I did films with 35mm with big crews, producers, the normal things. When I got fed up and didn’t know what to do, one of the things that saved me was those small digital cameras. I thought of doing something on 16mm with two or three friends, but even that was very expensive and technically too difficult for the thing we wanted to do. I did Vanda in 1998, a long time ago, and I guess I was one of the first to use those cameras. It’s a bit pretentious to say that the small camera was just the same as the others, but it was. I thought about it like the others. At first I didn’t believe in the digital thing, I thought it was very poor, but then slowly it became part of the day by day work. It dissolved everything that was technical, all the ambitions of having something else dissolved in this routine. What was good about it was that I found a routine that I never had in cinema. Every day, more or less, when I didn’t shoot I was doing something else. But it’s now been twenty years, and I see digital replacing the oldest ghosts of cinema again. Everything that I thought was over is coming back. Ghosts, projections… You have seen films by Murnau or Lang: it’s very different. You cannot fake it. You cannot do it again, you have to do something else, but you have to break a little, be a bit violent, not gentle. You cannot be gentle with Murnau or Lang. The way people are, speak, act: they are from today. This is today. That woman: I know her. And I don’t see that in today’s cinema. Films by Warhol or Straub: that is the revolution. Proof is: nobody sees them.