By Jacques Rancière

Originally published as ‘Arithmétiques du peuple (Rohmer, Godard, Straub)’, Trafic, n° 42, Summer 2002.

1. Multiplication

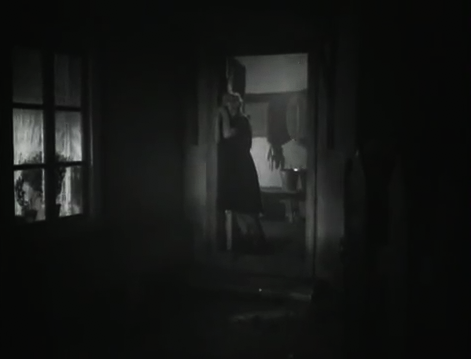

An aquarelle with delicate tones: noble facades, clear perspectives, only populated with some small time characters establishing the scale and animating the decor. Here abides Grace Elliot, the beautiful Englishwoman, but also and foremost the illustrious sweetness of living we always tend to ignore, since we haven’t lived before the Revolution. A lot of effort has been made to herald L’Anglaise et le Duc as an account of a political thinking, opposing the good Revolution – monarchic, liberal and enlightened: in short, the Revolution without revolution – with the bad one – revolutionary, Jacobin and terrorist. It doesn’t seem like Rohmer has spent a lot of energy defending this pious way of thinking, nor has he credited his heroin with an elaborated political vision. Leaving aside the classical opposition of the feminine law of the heart with the tortuous calculation of masculine reason, the politics of his film is completely visual: a catastrophe of a decor. It finds itself invaded with a multiplicity of people who are evidently not in their place there. It’s the definition itself of the people: those multiplying without any reason and proliferating where there is nothing to do. Old problem, comparable to those which fascinated Marx: what to do with all those people who are redundant in the light of what is required for housing service? If the theoretical response presents all sorts of difficulties, the visual response is well known: those who are redundant generally don’t look good and willingly elude their idleness by showing off heads on spikes. Of course these redundant hordes fatally end up surging back to the houses and pulling out the owners to detain them within reach of their drunken breaths and lecherous desires. Rohmer has been praised for courageously overturning the dominant opinion on the Revolution. In reality the boldness is quite limited: already some time ago Tocqueville, Augustin Cochin and Furet have taken the place of Mathiez and Soboul in the dominant opinion*. What is telling is rather the way in which Rohmer puts iconography in agreement with the opinion: the complex and contradictory popular figures, affected by the post ’68 era, are supplanted by a blunt return to the stereotypes of the huge popular animal: boorish, bawling and lecherous. Rohmer has also been praised for presenting Robespierre in a favorable light: after all, he releases the Englishwoman after being victim of obtuse informers. But “the Incorruptible” only lends his face to a repetitive episode: each time the plebs and its representatives threaten the Englishwoman, she is saved through the intervention of a man who has good manners and knows how to impose them on the brute plebs. All the visual politics of the film is there: in the evidence that educated people and good manners always go hand in hand, that the only crime, the unforgivable crime, is opening the gates for the furious surge of the multiple.

The maxim is not new. What is, by contrast, is the artistic and technical solution to the problem. For those people invading the beautiful tableaux, the technique offers a solution to discipline and finally dissolve them. The strings restricting them in the studio allows for their digitized image to be embedded flawlessly in the painted decor. For those who, two centuries ago, deviously wallowed in the decors of elegant life, the digital technique offers a a way to put them back in their place, to animate or delete their image at will. Of course this doesn’t work without some kind of retraction in regards to the idea of cinematographic modernity itself. The studio voyages of the beautiful Englishwoman between the hotel and her painted land house, like her devotion for the insignificant Champcenetz, close off the era of the camera in the streets, exemplified by the suburban voyage of another “foreigner”: the wanderings of Ingrid Bergman / Irène in Europa 51 at the end of the bus line, in the land of factories, lumpen-proletariat and prostitutes. This voyage in reverse was already imagined in the first shot of Conte de printemps, where we see the heroine cunningly leaving her school in the northern banlieu. But the voyage in reverse here is not only fictional. It is profoundly esthetic. L’Anglaise et le Duc marks, rather than the farewell to a Revolution that has never been Rohmer’s affair, a farewell to Rossellini, to a certain idea of cinematographic modernity associated with the liberty of the wandering camera and the truth of bodies in their place.

2. Substraction

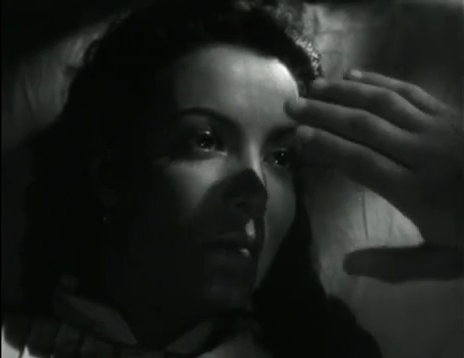

Godard, he remains loyal to the streets. It could even be said that he returns to them in Eloge de l’amour, leaving the shores of Lac Léman for the streets of Paris, even returning to the cinematographic color of the streets, for him and his characters to dwell in: the black and white of A bout de souffle and Bande à part, of Roma, città aperta and Europa 51. For him, in contrast to Rohmer, the streets cannot present any threat. What the streets allow to encounter, except for the homeless tramps one stumbles upon or the fugitive silhouettes evoking Balzac, is utterly the absence of the people. It is well known, they are always further away, just like the heroin in the film – the only actress suitable for the film, the tainted love who disappears, leaving only a book in a bag behind. Like her, it is in vain that we look for them there, beyond the city gates, on those dead end tracks where the legion of the damned cleans the trains at night, at a time when footsteps resonate in the deserted canteens. This is also the lesson of the long shots on the island of Seguin*, in front of which linger the maker of the film that won’t be made and the actress that won’t be in it. It was here that in 1968 students came to fraternize with the workers who had taken refuge in their fortress. Today the fortress is empty, its people parodied by a group of gardeners, carrying spades and rakes by way of sickles and hammers, metonymized by the passage of a barge on the river and the music of a song from L’Atalante*. The music is faded, the gardeners are disabled, and the empty fortress gives way to a night asylum where misery without a face seeks shelter, where a bewildered old Jew is gently rinsed under a shower, leaving the spectator free to bring to mind other “shower rooms”, in the same way other trains might come to mind when seeing the ones coming solemnly to a halt on the end tracks.

The people is missing. You don’t need Klee or Deleuze to know. It goes back even further, to the times of Marx who, in The Holy Family, dismissed the people of Eugène Sue* – that is to say, antecedently, the people of Rohmer. It was Marx who made the people with unspeakable features into a name without a face. The people is what is not there yet, not in the right place, never ascribable to the place and time where anxieties and dreams await. This is what the good marxist Francis Jeanson already tried to convey, on the dawn of ’68, to the little brainless “Chinoise” during a train ride in the outskirts of Paris*. There is no reason to despair for that matter. It is this absence that gives way to the power of phrases and the charm of refrains – their equivocation in itself: the small melody of the absent people brings us fluently from the song of L’Atalante to the Testament written by the convict Brasillach in imitation of Villon*, and of which the accents here call to mind Léo Ferré singing Aragon*. It is also this absence dismantling fictions. History withholds histories, Godard doesn’t stop telling us, taking here as witness a forgotten and confiscated Resistance. And what else is History but the linking of master signifiers? The bemoaning is in fact the flip-side of a complicity. The melancholic only lives off the substraction he denounces. The default of presence, the rupture of History, the lack of bodies of the people, all this is necessary for the beauty of the gesture, of the image, of the phrase opening and never finishing the praise of love. If History is worn out, if the people is not there, fiction won’t be there either – this collection of obscene images and phrases that always lie.

3. Division

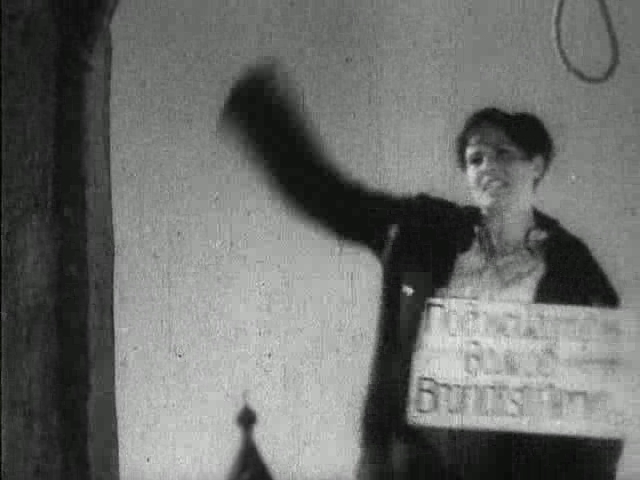

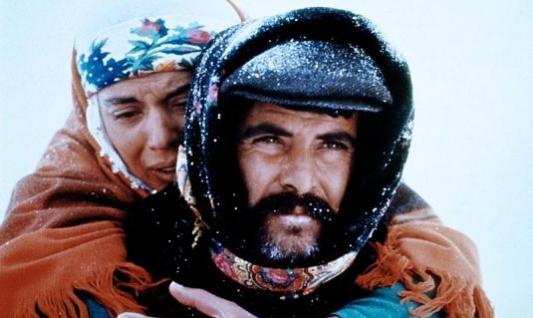

This melancholy of art has no merit for the Straubs. Yet for them too the people are made out of words and phrases. But phrases are not the beings without bodies that every mouth in Godard’s work can claim – and more often than not a mouth that is absent. Here phrases are rather propositions that are always verifiable, always conveyed by bodies that are accountable. “Workers, peasants, we are…”: the “subject” of Operai, Contadini is offered by the words opening the last verse of the Internationale. But the subjects that these words appoint are there, embodied. Which doesn’t mean that the habitus of the characters authenticates them. Even if the countrywoman wears a scarf, the chief a leather jacket and the doctor a suit, no truth of the words is produced by these accessories. The insistence with which we are shown these notebooks decorated with colored signs and these eyes mostly lowered in order to read them, at other times raised, as if to defy those accusing the word of lying, amply demonstrates it: the truth of words stems entirely from the text and the way in which the readers account for it. The people is what is spoken by bodies taking its part. And, of course, everything plays out in the specificity of this embodiment. One words resumes this: division. This is the specific idea of the people that Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huilet have retained from the times of Mao and Brecht. The people is not simply the subject abiding the ordeal of division in the difficulty of struggle (the “contradictions among the people”). It is the subject defined by division, proven by it. The people is what divides itself, standing together and asserting itself in its division.

The narrative of the argument is seemingly not original. Peasant’s respect for the earth, the seasons and the rhythms of the body, against worker’s fever for cement, electricity and exploit. The rigor of the chiefs, in charge of tomorrow, against the complaisance of individuals with everyday needs and grieves. Women’s irony towards the childish desire of men to find in them a mirror to attest to their bravery. It has been repeatedly told in chronicles and invested in bodies in fictions. Surely Vittorini’s prose already gives the chronicle of the divided people a dimension of Hölderin-like drama. Remains the straubian singularity stemming from the dispositive of talking bodies, ensuring embodiment to the detriment of fiction. The four groups of talking bodies are here at the same time the Brechtian craftsmen of a dialectical explication and the Virgilian witnesses of an idyll: the struggle of the worker’s fire and the peasant’s earth, epitomized at length, is resolved in the flame crackling with laurels, cooking the ricotta to be shared fraternally. The dialectical war is transformed – like in Vittorini’s work and, of course also in Pavese’s Dialoghi con Leucò – in a mythological mise-en-scène of conflicting forces. The mythologization of dialectics usually brings about some pessimist gap where the earth figures the inviolable withdrawal of nocturnal forces, of which the resistance forfeits the Promethean fire to futile smoke or devastating flame. Already Dalla Nube alla Resistenza had a tendency to inverse the Pavesian movement from history to myth. Here the rigor of dialectics and the melancholy of myth is resolved en oratorio, affirming the salvation by the division of voices. The commune of workers-peasants does not end due to its empirical failure, but is rather suspended in the evocation of an unitary incursion in search for laurels. Earth and fire are reconciled in light air. The final movement of the camera on the wooded hills, even though it doesn’t show us laurels, leaves us in the overture of reconciled elements and available horizon. This is the lesson proposed by the filmmakers: nothing has changed of what the words say, as long as the bodies stand at their service. The readjusted look, as if defying the officer or the judge demanding accountability from those bodies speaking of their illusions, gains the confidence once put into words by Mallarmé: “we were two, so my mind declares”*

——————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Translated by Stoffel Debuysere (Please contact me if you can improve the translation).

In the context of the research project “Figures of Dissent (Cinema of Politics, Politics of Cinema)”

KASK / School of Arts

translator’s notes

* The “revisionism” of the likes of François Furet and his antecessors Alexis de Tocqueville and Augustin Cochin, breaking with the “committed” tradition of Albert Mathiez and Albert Soboul, boils down to the dismissal of the revolutionary significance of 1789, instead presenting it as a series of historical facts. This trend has been confronted head on by Rancière, Badiou and others.

* The Renault motor car factory in Paris, at Boulogne-Billancourt on the island of Seguin, about 3 km downstream from the Eiffel Tower, was an icon of 20th century manufacturing industry in Europe. The factory became a symbol of the working class movement in France. It was occupied in 1936 by workers supporting the Popular Front, and was prominent in the agitations of 1968, when the philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-80) spoke to workers at the factory gates. It was completely closed down in 1992.

* The song in Jean Vigo’s L’Atalante (1934) is ‘Le Chaland qui passe’, which is the French version of the Italian song ‘Parlami d’amore Mariu’s, written by Vittorio de Sica for his 1932 film Gli Uomini, che Mascalzoni. Due to the success of the song, Vigo’s film would later also be released under the song’s title.

* Eugène Sue’s novel ‘Les Mystères de Paris’, a successful mixture of moralizing melodrama and social criticism, was first published in 1842–43. The book was mostly praised for drawing the attention of the prosperous classes to the misery which they tried to ignore, amongst others in a periodical called ‘Die Allgemeine Literaturzeitung’, founded by Bruno Bauer, a leading figure among the “Young Hegelians.” The reviews were written by a young man called Szeliga, who took Sue very seriously, and sought to give his views the sanction of the Hegelian philosophy. Marx and Engels’ ‘La sainte famille’, published in 1845, was intended as a general attack on the ideas of Bauer and Szeliga. Two long chapters of the book, written by Marx himself, are given over to a destructive analysis of the moral and social ideals recommended in ‘Les Mystères de Paris’.

* Leo Ferre chante Aragon (1961) was one of Ferré’s most popular albums. The songs were based on texts by Louis Aragon, poet, novelist, editor and a long-time member of the Communist Party. See here for the links between Aragon and Godard.

* According to Godard “the days of [Vichy propaganda minister and Milice member Phillipe] Henriot’s assassination (in 1944) and of the execution of Robert Brasillach, the right-wing critic and novelist and anti-Semitic, pro-Nazi propagandist (in 1945) were days of mourning in the Godard house.” Brasillach was also the author, with Maurice Bardèche, of the first Histoire du cinéma (1935), “the only one I ever read”, says Godard. It is no surprise then that he emerges in Histoire(s) du cinéma. Towards the end of part 1A ‘All the histories’ (1998 re-edit), Godard uses footage of a condemned prisoner being tied to a post, superimposing words taken from Aragon’s ‘The Lilacs and the Roses’. The sequence continues with images of a different execution, and words from a resistance poem by Paul Eluard; on the soundtrack is also a voice singing some lines from Brasillach’s ‘Testament d’un Homme Condamné’, which is inspired by the ‘Testament’ of another French poet, François Villon. Eloge de l’amour also features a reading of Brasillach’s “Testament”. For a discussion on this topic, see here.

* French philosopher Francis Jeanson, known for his involvement with National Liberation Front (FLN) militants during the Algerian War of Independence, has a part in Godard’s La Chinoise, in which he has a discussion with Anne Wiazemsky, playing a naive student extremist. See Rancière’s ‘The Red of La Chinoise.

* “Nous fumes deux, je le maintiens” is taken from Stéphane Mallarmé’s ‘Prose pour des Esseintes‘. See also Rancière’s Mallarmé: La politique de la sirène and Politique de la Literature. Alain Badiou wrote about this poem that “at issue is to establish an intelligible Place, a pure multiple, naturally one drawn and composed in the light”.

Prose

(For des Esseintes)

Hyperbole! can you not rise

from my memory triumph-crowned,

today a magic scrawl which lies

in a book that is iron-bound:

for by my science I instil

the hymn of spiritual hearts

in the work of my patient will,

atlases, herbals, sacred arts.

Sister, we strolled and set our faces

(we were two, so my mind declares)

toward various scenic places,

comparing your own charms with theirs.

The reign of confidence grows troubled

when, for no reason, it is stated

of this noon region, which our doubled

unconsciousness has penetrated,

that its site, soil of hundredfold

irises (was it real? how well

they know) bears no name that the gold

trumpet of Summertime can tell.

Yes, in an isle the air had charged

not with mere visions but with sight

every flower spread out enlarged

at no word that we could recite.

And so immense they were, that each

was usually garlanded

with a clear contour, and this breach

parted it from the garden bed.

(translation by E. H. and A. M. Blackmore)