“You can’t steal a gift. If you can hear it, you can have it”

– Dizzy Gillespie to Phil Woods in 1956, talking about Charlie Parker’s music and its influence on Woods

I’m preparing a little article for RUIS about music in the era of intellectual property, network technology and remix culture, partly in response to the proposed copyright extension (see previous post). So I went through my record (and file) collection a bit, tracking down some traces of “sampling” and “remix” practices. For your pleasure, here are some fine early and contemporary examples of (technological and explicit) musical appropriation and re-organisation.

Richard Maxfield, Amazing Grace, 1960

[audio:Maxfield_amazing-grace.mp3]

Richard Maxfield (US, 1927-1969) is one of the little-sung names in American avant-garde music. “For someone nearly forgotten today, Maxfield had a tremendous impact—largely through his classes at The New School in New York, which attracted radically avant-garde musicians such as Joseph Byrd, Dick Higgins, and even John Cage himself. Born in Seattle in 1927, Maxfield had studied with Krenek, Babbitt, Sessions, and Dallapiccola, but left this Eurocentric background behind to move toward a Cagean experimentalism.” Eventually he made contributions to the so-called “minimalism” movement, while forecasting a wide range of developments in the future of electronic music. ‘Amazing Grace’ mixes tape loops from two sources: a speech by revivalist James G. Brodie and electronic fragments from an opera Maxfield had made in 1958 entitled ‘Stacked Deck’. The loops play back at various speeds, causing the fragments to overlap in complex ways. This method would later be explored further by Terry Riley, Steve Reich and others. “It is astonishing how many threads of 1960s music seem to begin with the ideas Maxfield explores, and it is a tragedy that his early death, from leaping out a window at age 42, kept him from participating in the more rewarding scene that would later appear.”

available on ‘Oak of the Golden Dreams’ (New World Records)

James Tenney, Collage No. 1 (“Blue Suede”), 1961

[audio:Tenney_Collage1.mp3]

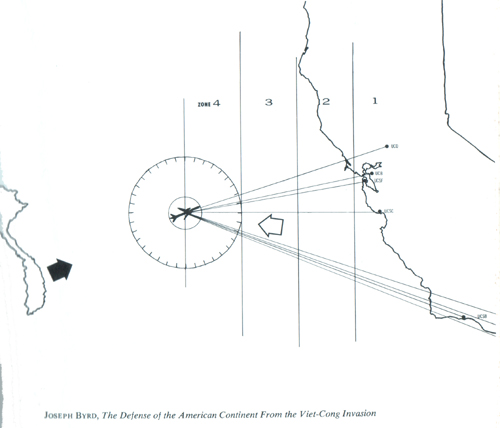

James Tenney (US, 1934-2006) must be one of most stylistically diverse composers in 20th century music, having studied or worked with a host of famed American mavericks, including Harry Partch, Edgard Varese, Carl Ruggles and John Cage. From orchestra pieces to tape works, from serial procedures to minimalism, from explorations in microtonality to collage: “he mended the differences between musical worlds and bridged the gaps between extremes” (Jenny Lin). One of those gaps was between the so-called “avant-garde” and pop music. In 1961 he worked on ‘Collage No. 1 (“Blue Suede”)’ in an electronic music studio at the University of Illinois. It was just five years after the release of ‘Blue Suede Shoes,’ the Elvis Presley record which he sampled (which is in itself a version of a Carl Perkins song). This track was later used by Stan Brakhage as a soundtrack for his Christ Mass Sex Dance (1991), composed of six rolls of superimposed images as a “celebration of the balletic restraints of adolescent sexuality─shaped (in this instance) by The Nutcracker Suite of Tchaikovsky as well as the gristly roots of Elvis Presley”. Brakhage and Tenney were actually really good friends, ever since they worked together on Interim (1952), Brakhage’s first film (he was 19 years old) and Tenney’s first composition (who was 18). They remained friends and collaborators for the rest of their lives. Tenney made another tape collage in 1967: Collage #2 (Viet Flakes), which is the soundtrack to a film of the same name, by (then partner) Carolee Schneemann (he also appears in her wonderful Fuses). The film is a collage of violent images from the Vietnam War, while Tenney’s composition collages bits of audio from sources such as Vietnamese and Classical music, along with American Pop music.

available on ‘James Tenney: Selected Works 1961-1969’ (New World records)

Milan Knizak, Composition No. 3, 1963-64

[audio:Knizak_compostition-no3.mp3]

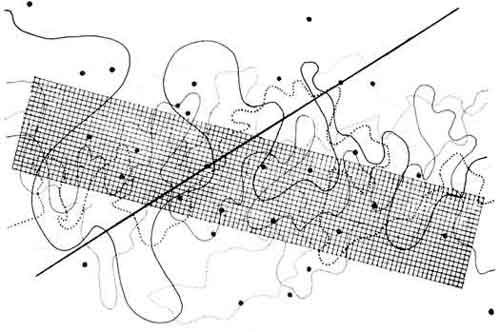

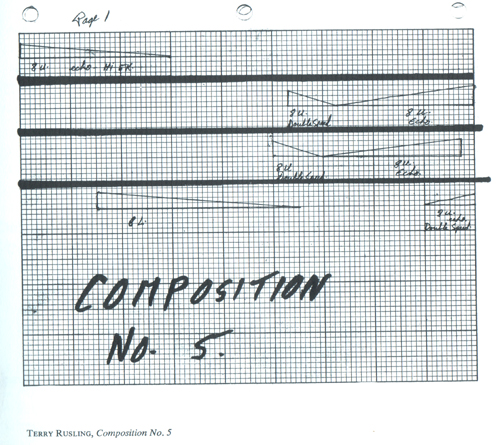

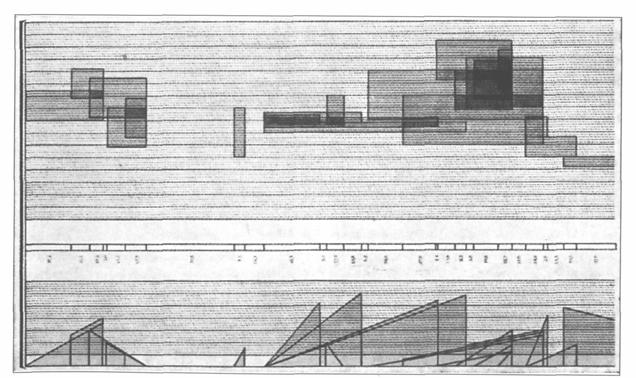

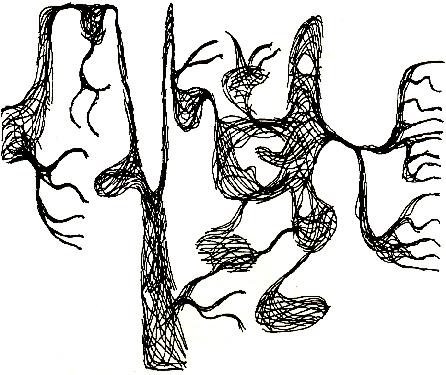

I recently discovered Milan Knizak’s Broken Music, which was first published in 1979, but reissued on CD by Ampersand in 2002. Knizak (CZ, 1940) is a wellknown Czech artist, who was a member of the Fluxus movement in the 1960’s and founder of the short-lived but influential rock project ‘Aktual’ (1967 – 1971). Together with other Aktual members, Knizak put on (and was arrested for) some of the first aesthetic “happenings” in Eastern Europe, which blended sculpture, music and audience participation. The pieces on Broken Music are part of his “Destroyed Music” series, music and sculpture made out of scratched, warped, defective and damaged records. Knizak acquired a gramophone and collection of records and experimented by playing them speeded up or slowed down, and later damaging them by burning them, gluing layers on, putting together bits of different records, scratching and so on. He wasn’t the first to do this – Hongarian constructivist László Moholy-Nagy did similar experiments in the 1920’s, for example – but Knizak developped these ideas further. He wrote: “In 1963-64 I used to play records both too slowly and too fast and thus changed the quality of the music, thereby, creating new compositions. In 1965 I started to destroy records: scratch them, punch holes in them, break them. By playing them over and over again (which destroyed the needle and often the record player too) an entirely new music was created – unexpected, nerve-racking and aggressive. Compositions lasting one second or almost infinitely long (as when the needle got stuck in a deep groove and played the same phrase over and over). I developed this system further. I began sticking tape on top of records, painting over them, burning them, cutting them up and gluing different parts of records back together, etc. to achieve the widest possible variety of sounds. A glued joint created a rhythmic element separating contrasting melodic phrases… Since music that results from playing ruined gramophone records cannot be transcribed to notes or to another language (or if so, only with great difficulty), the records themselves may be considered as notations at the same time.” Knizak not only started seeing his treated records as a certain kind of musical notation in itself, but he also decided to treat traditional scores in the same way as the records. In a later phase, he started treating the records as “art objects” as well, focussing on their visual, decorative aspects.

available on ‘Broken Music’ (Ampersand)

Arthur Lipsett, Free Fall, 1964

[audio:Lipsett_FREEFALL.mp3]

I’ve posted about Lipsett’s (CA, 1936-1986) work on several occassions now, so no need to introduce him again, I guess. This piece is the soundtrack of his 1964 film Free Fall. It is featured on a compilation of his soundtracks, recently published by Global A. The importance of sound in his work, as instructions for observing and critiquing the images, is highlighted by this piece, which illustrates Lipsett’s highly structured system of field recordings, loops, speech and music. In the proposal for Free Fall he describes the film as an “attempt to express in filmic terms an intensive flow of life – a vision of a world in the throes of creativity – the transformation of physical phenomena into psychological ones – a visual bubbling of picture and sound operating to create a new continuity of experience – a reality in seeing and hearing which would continually overwhelm the conscious state – penetration of outward appearances – suddenly the continuity is broken – it is as if all clocks ceased to tick – summoned by a big close-up or fragment of a diffuse nature – strange shapes shine forth from the abyss of timelessness.” Free Fall features dazzling pixilation, in-camera superimpositions, percussive tribal music, syncopated rhythms and ironic juxtapositions. Using a brisk “single-framing” technique, Lipsett attempts to create a synesthesic experience through the intensification of image and sound. Citing the film theorist Sigfreud Kracauer, Lipsett writes, “Throughout this psychophysical reality, inner and outer events intermingle and fuse with each other – ‘I cannot tell whether I am seeing or hearing – I feel taste, and smell sound – it’s all one – I myself am the tone.’” Incidentally, Free Fall was intended as a collaboration with the American composer John Cage, modeled on his system of chance operations. However, Cage subsequently withdrew his participation fearing Lipsett would attempt to control and thereby undermine the aleatory organization of audio and visuals. (Thx, Brett Kashmere)

available on ‘Soundtracks’ (Global A)

Steve Reich, Come Out, 1966

[audio:Reich_Come-Out.mp3]

Steve Reich (US, 1936) was asked to write this piece to be performed at a benefit for the retrial of the Harlem Six – six black youths arrested for committing a murder during the 1964 Harlem riots for which only one of the six was responsible. Truman Nelson, a civil rights activist and the person who had asked Reich to compose the piece, gave him a collection of tapes with recorded voices to use as source material. Presumably, Reich’s response was: “Look, I’ll do this, and I’ll do it for nothing, but you’ve got to let me make a piece out of anything I find.” Nelson, who chose Reich on the basis of ‘It’s Gonna Rain’, made the year before, agreed to give him creative freedom for the project. Reich eventually used the voice of Deniel Hemm, one of the boys involved in the riots but not responsible for the murder. In the interview he says: “I had to, like, open the bruise up and let some of the bruise blood come out to show them” (alluding to how Hamm had punctured a bruise on his own body to convince police that he had been beaten). The police had not previously wanted to treat Hamm’s injuries, since he did not appear seriously wounded. Reich re-recorded the fragment on two channels, which initially play in unison. They quickly slip out of sync to produce a phase shifting effect. Gradually, the discrepancy widens and becomes a reverberation and, later, almost a canon. The two voices then split into four, looped continuously, then eight, until the actual words are unintelligible. The listener is left with only the rhythmic and tonal patterns of the spoken words. Reich says of using recorded speech as source material that “by not altering its pitch or timbre, one keeps the original emotional power that speech has while intensifying its melody and meaning through repetition and rhythm”. This piece has been used in 1982 by the Belgian choreographer Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker as part of one of her seminal works entitled Fase. It was also (re)sampled by Madvillain, UNKLE and many others.

available on ‘Early Works’ (Nonesuch)

Terry Riley, You’re No Good, 1968

[audio:Riley_You’re-No-Good.mp3]

In 1967 Terry Riley (US, 1935) was playing one of his “All Night Flight” concerts in Philadephia, featuring his soprano saxophone, keyboards, and tape delay devices, which went on for hours in the trance-inducing Minimalist fashion. After the show the proprietor of a local discotheque asked Riley to compose a piece to be played in his club, and Riley obliged with a version of Harvey Averne’s ‘You’re No Good’, a single off Averne’s 1968 Atlantic LP Viva Soul. Riley took the Motown-inspired pop tune and transformed it into a twenty-minute exploded view, slicing the track into long and short bits and looping them, as Steve Reich had done a few years earlier. The Riley remix is wonderfully perverse: beginning with a two-and-a-half-minute piercing sine wave drone, increasing in pitch to the point of unbearability before suddenly breaking into the Averne song, which becomes more and more fragmented and complex, towards the end adding Moog shrieks. This piece was used as a soundtrack for Nick Relph and Oliver Payne’s Mixtape (2002), a video that evokes youth through the carpe diem reappropriation of situations and objects. The soundtrack structures the video, determining its length and editing style.

available via the (Cortical Foundation)

Jon Appleton, Chef d’œuvre, 1967

[audio:Appleton_chef-doeuvre.mp3]

Jon Appleton’s (US, 1939) work was recommended to me by Aki Onda a few years ago. His electroacoustic music consists of three distinct approaches: the abstract manipulation of timbre, the compositions he made for Synclavier – one of the first digital synthesizers he helped developping – and the use of ‘found musics’ and recognizable objets sonores. ‘Chef d’œuvre’ is part of the last approach. He writes: “It is my Boléro. It is the work of mine that has been most frequently played and recorded. Using the sounds of a singing commercial for Chef-Boy-Ar-Dee pizzas by the Andrews Sisters, there is a frenetic pace and sense of humor which can be heard in subsequent works.” Also check out his excellent piece ‘Newark Airport Rock’, which was based on some interviews he did while he stranded by weather at the Newark airport on a night in 1967. He asked his fellow passengers “what do you think about the new electronic music?” and later assembled the choicest answers, placed them on a bed of sequenced, electronic sound produced by a Moog synthesizer. Also wortwhile: his 1969 collaboration with Don Cherry, released on Bob Thiele’s Flying Dutchman Label.

available on ‘Contes de la mémoire’ (empreintes DIGITALes)

Holger Czukay, Boat Woman Song, 1969

[audio:Czukay_Boat-Woman-Song.mp3]

Around the same time Holger Czukay (DE, 1938) started out with CAN, he teamed up with producer Rolf Dammers to record a solo album, titled Canaxis. Czukay was heavily influenced by Stockhausen, with whom he studied from 1963 to 1966, especially by his compositions Telemusik (1966) and Hymnen (1968), which used multitudes of inserted and altered ethnic recordings. “I wanted to come closer to an old, an ever-recurring dream” Stockhausen wrote about Telemusik, “to go a step forward towards writing, not ‘my’ music, but a music of the whole world, of all lands and races.” It’s no coincidence then that most of Canaxis is recorded on ‘pirated’ time in the Electronic Music Studios at WDR Köln, which was then led by Stockhausen himself. Czukay took Stockhausen’s methods and pushed them farther, precursoring the art and craft we now call “sampling”. This album was assembled from thousands of snippets recorded from short wave radio, a long standing obsession of Czukay’s which he also incorporated into some of Can’s later albums. ‘Boat-Woman-Song’ is the first track. This is what Head Heritage says about it: “it starts off with a fragment of an Adam de la Halle piece that Can also used on occasion in their earliest gigs. But Holger takes the last bit, this “Dee, dee, dee, dee, dee” phrase and begins to loop it. This becomes the underpinning for the first and last sections of the composition. A wailing vocal then overlays this, and the electronics phase in and out in a drifting interplay. But then, out of nowhere, this bass-propelled groove develops. And over the top, Holger drops in some Vietnamese singers. It’s this magic moment where we step away from just dropping bits of tape into the fray and into the first glimmers of sampling methodology. And it is nicely done, too. The rest of the track takes us back to the de la Halle loop, but now everything’s been shifted downward in pitch and tempo. The electronics re-enter, more abstract than in the previous…well, we’ll call it what it is…A section, and it’s these drifting electronic tones, like pitch-shifted horns, that lead us out of the work.” For many years Canaxis was a real rarity, as only 1000 copies were printed and it was only released in Germany, but now it has been reissued, including a one-off recording of a brief jazz composition from German radio, which was Czukay’s first broadcast work.

available on ‘Canaxis’ (Mute)

Jan-Olof Mallander, Degnahc Ev’uoy, 1970

[audio:Mallander_Degnahc-Evuoy.mp3]

J.O. Mallander (FI, 1944) is a swedish-finnish artist who worked within the infamous Sperm collective in the late 1960’s, along with Matti-Juhani Koponen and other visual and musical artists. He is reported to be the one who brought back the infamous Velvet Underground flexidisc from Aspen magazine (in NYC) which was a huge influence on Pekka Airaksinen, the musical force of Sperm. It was these frequent boat trips (he would work there) that gave him the opportunity to experience the massive artistic revolution of the time. He met and became friends with Nam June Paik and connected with the Fluxus movement. Mallander’s first musical outing, the single ‘1962/1968’ from 1968, was based on the sounds of vote-counters repeating “Kekkonen”, the name of the overwhelming winner the presidential elections in 1962 an ’68, over and over again. In 1970 his ‘Decompositions’ ep was published (on LOVE records), on which he deconstructed well-known jazz recordings by deliberately jumping the needle of the record player or changing the structures of the songs. ‘Degnahc Ev’uoy’ was one of the tracks on this ep and basically consists of the jazz standard “You’ve Changed” played backwards. I also read about his piece ‘In Reality’, made in 1969 for the Text-Sound festival in Stockholm, which seems to be a collage of various versions of Cole Porter’s ‘I Got You Under My Skin’, slipping in and out of loops. I haven’t heard it yet, so if anyone could tell me where I could find it… I’m really curious.

available on ‘More Time – Hits & Variations 1968-1970’ (Anoema recordings)

John Adams, Christian Zeal and Activity, 1973

[audio:Adams_christian-zeal.mp3]

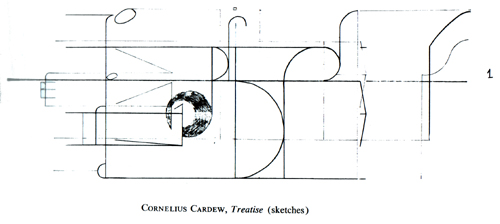

‘Christian Zeal’ is from John Adams’s (US, 1947) early period of composition and part of the triptych ‘American Standard’ (this is the original version, which was released on Brian Eno’s Obscure label. I left part 3 in). Adams wrote about it: “American Standard was written under the influence of the English experimental composers of the 1960’s, particularly Cornelius Cardew and the Scratch Orchestra. Cardew’s aim, in keeping with this anti-elitist politics of art, was to create a kind of new Gebrauchmusik, a body of work that could be played by performers with only the minimum of technical abilities. But now, twenty years later, I realize that my New England sensibilities still came through loud and clear in Christian Zeal & Activity, and the mixture of the serene, almost stationary homophonies of the hymn, contrasted with the gritty, active sound of the human voice, was a subconscious reenactment of the scenario of Ives’ Unanswered Question.” ‘Zeal’ is constructed of a simple chorale-like chordal structure played by strings and a sparse woodwind section. A series of suspensions delays resolution of the harmonies until the very end of the piece, with only a few authentic cadences throughout the piece. The unique aleatoric element is what really makes the piece special. The conductor is directed to place “sonic found objects” into the composition. Originally a an unedited recording of a 1971 sermon was used. In more recent versions, Edo De Waart, conductor of the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra spliced and looped this recording, drawing even more emotion from the pastor’s words and from the music itself. The piece has recently been ressurected: in January 2008 it was performed as part of a concert from the Wordless Music Series in New York City, alongside pieces of Jonny Greenwood and Gavin Bryars.

The new version is available on Adams’ Earbox collection.

Gavin Bryars, Jesus Blood Never Failed Me Yet (excerpt), 1975

[audio:Bryars_Jesus_Blood_Never_Failed_Me_Yet.mp3]

In the words of Gavin Bryars (GB, 1943) himself: “In 1971, when I lived in London, I was working with a friend, Alan Power, on a film about people living rough in the area around Elephant and Castle and Waterloo Station. In the course of being filmed, some people broke into drunken song – sometimes bits of opera, sometimes sentimental ballads – and one, who in fact did not drink, sang a religious song “Jesus’ Blood Never Failed Me Yet”. This was not ultimately used in the film and I was given all the unused sections of tape, including this one. When I played it at home, I found that his singing was in tune with my piano, and I improvised a simple accompaniment. I noticed, too, that the first section of the song – 13 bars in length – formed an effective loop which repeated in a slightly unpredictable way. I took the tape loop to Leicester, where I was working in the Fine Art Department, and copied the loop onto a continuous reel of tape, thinking about perhaps adding an orchestrated accompaniment to this. The door of the recording room opened on to one of the large painting studios and I left the tape copying, with the door open, while I went to have a cup of coffee. When I came back I found the normally lively room unnaturally subdued. People were moving about much more slowly than usual and a few were sitting alone, quietly weeping. I was puzzled until I realised that the tape was still playing and that they had been overcome by the old man’s singing. This convinced me of the emotional power of the music and of the possibilities offered by adding a simple, though gradually evolving, orchestral accompaniment that respected the tramp’s nobility and simple faith. Although he died before he could hear what I had done with his singing, the piece remains as an eloquent, but understated testimony to his spirit and optimism.” The piece was first performed at the Queen Elizabeth Hall in December 1972, recorded and (also) released on Brian Eno’s Obscure label in 1975 (limited to a duration of 25 minutes). A substantially revised and extended version, featuring Tom Waits singing along with the original recording, was published on Point Records in 1993. William Forsythe used the piece as the score for a dance piece.

available on Point Music

Part 2